India’s space diplomacy got a major boost last month with the launch of the South Asia Satellite, envisaged in June 2014 by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi as “India’s gift” to the South Asian Association for...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Manipulating Audiences With the "Contrast Principle"

It would seem impossible for the Taliban to get good publicity in Western media, but the unthinkable nearly happened on December 16, 2014. How? The Taliban tricked the press by using a powerful communications technique: the contrast principle.

Here is how it works: when two things are presented in sequence, we tend to see them as more different than they really are. Below, I describe three examples of how the contrast principle has recently influenced public diplomacy and the mass media.

[The contrast principle] can make a bad apple look good – when it’s compared with an even worse apple.

1) The Afghan Taliban Condemns the Pakistani Taliban

On the morning of December 16, 2014, nine gunmen from the Pakistani Taliban opened fire on children and staff at the Army Public School in Peshawar, killing more than 140 people.

The news shocked the world. Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif called it a “tragedy unleashed by savages.” President Obama said it was a "heinous attack," and Ban Ki-moon denounced it as “an act of horror.”

In a surprise move, the Afghan Taliban issued a statement claiming that “the intentional killing of innocent people, children and women is against the basics of Islam and this criteria has to be considered by every Islamic party and government."

The statement contrasted the Afghan and Pakistani Taliban: the denouncement of the school attack created an illusion that the Afghan Taliban is different from the Pakistani Taliban – that out of the two groups, the Afghan Taliban are “the good guys.”

Covering the statement, Reuters issued a story with the headline “Afghan Taliban Condemns School Attack by Pakistani Taliban.” Similarly, EURONEWS reported that the “Afghan Taliban Condemn Pakistani Taliban Attack on Peshawar School.”

Many in the security and diplomatic community commented on this attempt to manipulate the news. For example, the European Union Special Representative in Afghanistan, Franz-Michael Mellbin, succinctly tweeted from his handle @AmbMellbin: "Sad to see some press quoting #Afghan #Taliban on #PeshawarAttack without mentioning they have repeatedly attacked Afghan school children."

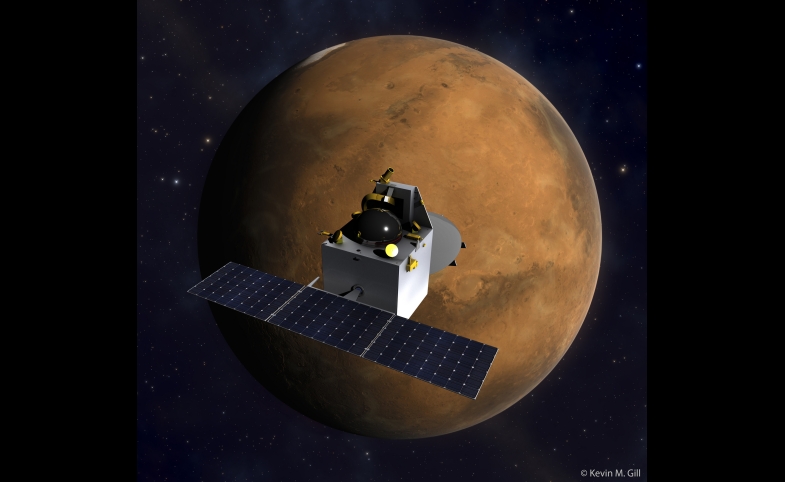

2) India’s Mars Mission Cheaper than the Movie Gravity

On September 24, 2014, two days before Prime Minister Modi’s historic visit to the U.S., India’s “low-budget” spacecraft entered orbit around Mars.

On the eve of Modi’s arrival, the event attracted the attention of American media, and India’s government creatively used the contrast principle to maximize the story’s effect.

They proclaimed the Mars mission “cheaper than the movie Gravity.”

The clever contrast between an actual space mission (with budget US$74 million) and the production of a movie about a space mission (with budget US$100 million) created a powerful effect.

It made a strong statement about the return on the investment.

CNN ran the story “India's $74 million Mars mission cost less than 'Gravity' movie,” while NBC News explained “Why India's Mars Orbiter Mission Cost Less Than 'Gravity' Movie.”

This framing persuasively communicated that India is the “low-cost high-tech” hub and a destination for research and development investments.

In addition, the comparison resonated far beyond its initial target, the U.S. investment community.

3) Hagupit versus Haiyan

The two examples above show intentional uses of the contrast principle. The following example is different because the contrast occurred unintentionally – and yet made an impact on how foreign audiences perceived the actions of another government.

On November 8, 2013, Super Typhoon Haiyan, the strongest tropical cyclone ever recorded, made landfall in the Philippines and destroyed an area as big as Belgium. More than 6,000 people died. Heartbreaking images of devastation trended on all media platforms and unleashed scrutiny of the government’s preparedness for the storm.

A year later, in December 2014, another Super Typhoon – named Hagupit – formed in the western Pacific. “The strongest storm of the year anywhere on the planet is zeroing in on the Philippines,” warned CNN on December 4. In anticipation of a massive disaster, the most important newsrooms in the world dispatched their teams to the Philippines.

The typhoon made first landfall on December 5, with maximum sustained winds of 175 km/h and gusts of up to 210 km/h (comparable to Hurricane Sandy which hit New York City in 2012).

The impact, however, was different than Haiyan’s. The government used the 12 months between the two storms to improve early warning systems, contingency planning, evacuation routes, and train disaster response teams. AccuWeather wrote “More Than One Million Evacuated as Deadly Hagupit Lashes Philippines.” The BBC reported that “the Philippines looks to have averted disaster on a national scale.”

The official death toll from Hagupit was 18, as opposed to the 6,000 casualties after Haiyan. The Philippine Inquirer ran an op-ed appreciating the government’s response to Hagupit: “Congratulations are in order.”

This, and the gradual weakening of Hagupit, created the context for a contrast between the two storms. Although Hagupit affected 30 million people in the Philippines, in contrast with the destruction a year earlier, Hagupit appeared less significant. The reference to the first storm led to the conclusion that the second storm, Hagupit, wasn’t such a big deal.

As a result, many news crews dispatched to cover Hagupit were pulled out of the Philippines by December 9. The international coverage of the storm came to an end and almost no one reported on the success of the government’s response to the disastrous storm.

What’s the Lesson?

These three examples show the contrast principle’s potential to influence perceptions and choices. It can make a bad apple look good – when it’s compared with an even worse apple. The Taliban case in particular illustrates what a powerful tool of manipulation the principle can be. Its simplicity and easy application make it a powerful weapon of influence in communications and public diplomacy.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

March 22

-

February 23

-

February 22

-

March 4

-

April 11

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.