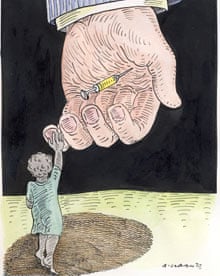

Did you drop your kids at the school gate this morning? Or perhaps you heard the chatter of a crowded school playground on the way to work? Well, imagine thousands of those voices silenced. By lunchtime on Monday, the fate of four million children across the developing world will be decided. This is the number of lives that can be saved by rolling out vaccinations in 70 of the world's poorest countries over the next five years.

The very scale of this – the zeros that bedevil global aid – makes it hard to grasp. Put a child in front of us, and most of us would do anything to protect her or his life; talk of four million, and a lot of people shrug their shoulders. On Monday morning, David Cameron – in his first major initiative in development diplomacy in the UK – will chair a summit for pledges to the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (Gavi). There's a shortfall of £2.3bn, and it's being seen as a litmus test of how well aid can survive in the age of austerity.

Quite frankly, child vaccines is the easiest sell in the aid business – if you can't raise money for this, you can't raise money for anything. Not only can you use photos of enchanting children all over your campaigning material – an opportunity that has not been missed by the NGOs that have been energetically drumming up support on both sides of the Atlantic – but the gut appeal of saving children's lives can be backed up by weighty analyses of this as one of the biggest win-win interventions in development aid.

Vaccinate a child and not only do you save lives, you also save many more children from the diseases that can cripple and stunt their physical and mental development – plus you save their families the costs of healthcare for their sick children. Disease is one of the major causes of poverty. And, if you are worried about global population growth, one of the most effective strategies is to reduce infant mortality. When more of their children survive, parents reduce their family size: the evidence is there. So even on this most neuralgic of debates – the age-old query of why do poor people have so many children – vaccinations offers the best answer.

But even with this armoury of arguments it's been tough going on making up the shortfall of £2.3bn in Europe and the US. The UK has remained admirably stalwart, but public attitudes towards development aid everywhere are sinking to an all-time low.

The One campaign's film succinctly captures a problem evident on both sides of the Atlantic. Stopping people in the street, it asked them how much the UK gave in aid. "Too much," was the near universal view – guesses came in at 10%-20% of government spending, even as much as an absurd 70%. They had little idea of what that bought: a few thousand schools perhaps?

When they were told that the true figure was 0.56%, and it saved millions of lives and bought millions more children an education, they professed to be astonished. This is the aid conundrum: resentment is deepening, awareness of the figures has gone askew and people have lost faith in its efficacy. If anything can shift some of this it would be vaccines. It's a textbook case of how aid can work, which is why Cameron and the development secretary, Andrew Mitchell, have made it a flagship policy since they arrived in government.

Their hope must be that they can begin to shift public aid scepticism ahead of the battle that lies ahead. Already Britain's aid budget is well ahead of other developed countries, at 0.56% of GDP compared with Germany's 0.38% or the US's 0.21%. Last week's sniping in the Daily Mail and the Express are only the opening skirmishes ahead of 2013, when the aid budget will jump by 33% to meet the target of 0.7% pledged for 2013.

Instead of incremental rises to meet 0.7%, the chancellor, George Osborne, plumped to backload it – significantly increasing the political risks. Cynics have been muttering about a sabotage strategy, but Cameron's passionate defence of aid at the G8 meeting last month makes it nigh on impossible now to backtrack. What's becoming clear is that the aid commitment is about more than detoxifying the Tory brand. It's about the novel notion of Britain as a "superpower of aid", as Sir John Major put it recently. The idea was quickly picked up and expanded by Mitchell. Just as the US is a military superpower, so the UK can be an aid superpower, he argued; a projection of power overseas of which the British can be as proud of as they are of the army or the monarchy.

It's a clever way to frame aid but it needs careful unpacking, because it has both some substance and the dangers of delusion – a tricky combination.

The substance lies in the fact that Britain is well out in front on aid, not just in terms of funding but also political commitment and expertise, as well as the effective advocacy and campaigning of big NGOs. Key players such as Bill Gates and the head of USAid, Rajiv Shah, are in town on Monday as Cameron plays the world statesman, tacit acknowledgement of the crucial UK role. Last month, the scourge of the aid industry as one of its most articulate sceptics, Bill Easterly, put the Department for International Development (DfID) top in his league of the world's aid agencies. We have a better reputation on doing aid than we have on fighting wars.

However, the delusions here are obvious: "superpower" is a peculiarly inappropriate term for the sensitivities of post-colonial collaboration with aid recipients. Aid has long been a way of securing status and prestige on the world stage, but this goes one step further. Ever wary of European self-aggrandisement, the term will bomb in Africa and even more so in India. Aid, it seems, is still tangled up in western power politics.

And there lies the rub, because this term speaks to an emerging debate in the US about aid as a political strategy: a way to project soft power, establish influence and spread values – which is often more useful than diplomacy or defence in a post-cold war world. This kind of argument for "smart power" also claims that aid is part of a security brief. If climate change and increasing natural disasters are likely to provoke huge disruption, aid policies on adaptation and resilience are a more constructive response than building aircraft carriers and missiles. There is plenty of sense in this – but also the risk that it skews aid priorities to serve national self-interest.

This kind of "smart power" strategy is an apt description for how China and Brazil are winning friends and admirers across the developing world. They do it without the quaint baggage of the British aid debate, with its overtones of charity and empire. The challenge ahead is all about communication, finding powerful ways to explain to a sceptical electorate that development issues such as feeding the world, water and health in the end affect us all. Stability, peace, prosperity: these cannot be simply national projects; global co-operation is a survival strategy. Four million children's lives saved by lunchtime would be a good morning's work.