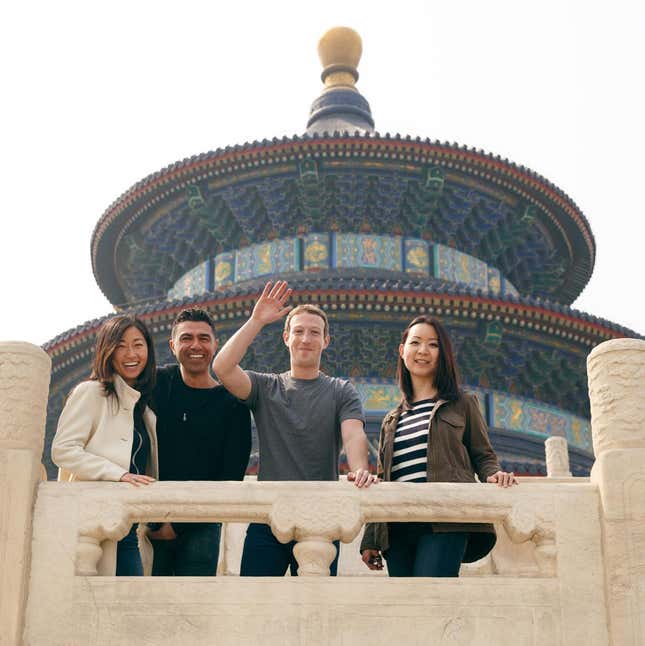

Mark Zuckerbeg’s charm offensive in China won’t let up. Over the past few days the Facebook founder and CEO published a controversial photo of himself jogging in smoggy Beijing, and met in person with China’s Minister of Propaganda—an unprecedented move for a foreign business owner. This follows his twenty-minute speech in Mandarin and meetings with Xi Jinping and China’s internet czar last year.

Zuckerberg’s goal, of course, is to bring Facebook to China, which has been blocked by Beijing since 2009. Adding just half of China’s 668 million internet users to Facebook would increase the social network’s total by 20%—and create a lucrative new market for advertising and publishing.

But launching Facebook in the Middle Kingdom as it exists in the rest of the world would be nothing short of a miracle. China’s restrictions on internet freedom and foreign tech companies have grown tighter, not looser, in the past decade. Authorities are cracking down on online dissent, journalism critical of the government, and even the use of VPNs, which were once quietly tolerated.

Instead, if Zuckerberg is lucky, authorities will permit a “localized” version of Facebook, with censored content and perhaps limited overlap with the international version. Various laws and statements, like the China Cybersecurity Law or the recent set of rules from the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television, dictate broadly how foreign internet companies ought to operate in China.

But a look at the on-the ground struggles of overseas tech companies in China is a better indicator of what to expect. Here are some steps Facebook will probably have to take if it enters China.

1. Store user data in China

A debate over how governments may or may not have the right to access company information stored overseas is currently taking place in the EU and US. Some parties, like the US government, feel that the location of a server is irrelevant, what matters is the company that owns it. While China hasn’t weighed in on actual court proceedings, its stance is nevertheless clear—data pertaining to Chinese citizens must be stored in China, where the government can access it whenever it wants.

Authorities have taken steps for this measure to be a legal requirement for all foreign companies. A draft version of the China Cybersecurity Law proposed local data storage as mandatory, but the final passed version omitted it. SARFT’s proposed regulations on foreign media companies also call for overseas media companies to do the same.

Regardless of the letter of the law, many foreign companies have already begun setting up servers in China. After a year of negotiations with authorities, Apple began storing user data from China on August 2014 in a local data center managed by China Telecom, one of the country’s state-owned carriers. Uber, LinkedIn, and Evernote have each done the same.

Facebook currently stores its user data in Oregon, North Carolina, Texas, and Sweden. But it’s already regularly compliant with local governments when it comes to requests to peek at data. Its policy statement reads:

We may access, preserve and share your information in response to a legal request (like a search warrant, court order or subpoena) if we have a good faith belief that the law requires us to do so. This may include responding to legal requests from jurisdictions outside of the United States where we have a good faith belief that the response is required by law in that jurisdiction, affects users in that jurisdiction, and is consistent with internationally recognized standards.

2. Partner with a local company

The Chinese government often requires foreign companies to form “partnerships” with domestic counterparts. The specifics of these partnerships vary depending on the business.

In January, Qualcomm announced a joint venture with the state-affiliated Guizhou Huaxintong Semiconductor Technology. It promised to invest in the development of chip server technologies, something the Chinese government has been keen to build on its own. Microsoft’s partnership with the state affiliated China Electronics Technology Group Corp, meanwhile, was designed to help “license, deploy, manage and customize” for Windows products used by government institutions.

In social media, partnerships appear to be more about entering China with trusted, well-connected hands. LinkedIn entered China through a joint venture with two domestic venture capital firms—Sequoia Capital China, which runs largely independently from its US counterpart, and CBC China, which is headed by a former colleague of the son of ex-president Jiang Zemin. Line, the Japanese chat app, partnered with local anti-virus app Qihoo 360.

During his meeting with Zuckerberg this week, China’s propaganda minister said he hoped Facebook could “share experiences and improve mutual understanding” with China’s internet companies. That statement could be empty diplomacy talk. Or it could be code for “find a buddy” and then share how the company works with them.

3. Create the “Great Firewall of Facebook”

Chinese authorities censor social media and the internet in two ways. The Great Firewall renders certain webpages inaccessible by redirecting traffic heading to blocked sites like Google or The New York Times to bogus IP addresses or error messages. They also control it by forcing internet media companies to censor content on their sites or apps. Typically, these companies use algorithms to identify posts with sensitive words and then prevent them from spreading. They also employ teams of human censors to manually remove posts that authorities might deem taboo.

Before Chinese authorities blocked it in 2015, Japanese messaging app Line relied on a keyword filtering system to make sure that politically sensitive topics couldn’t be discussed easily that was managed by partner Qihoo 360. LinkedIn, meanwhile, relies on both algorithms and in-house censors to remove content from its Chinese site, with help from two Chinese venture capital firms that helped fund its expansion.

If it were to enter China, Facebook’s massive global scale would probably call for the largest, most complicated censorship apparatus of any non-government media company on earth.

Messaging giant WeChat and the Twitter-like blogging platform Sina Weibo also actively censor content in China—but most of their users communicate in Chinese, making things somewhat easier. But on Facebook anyone can make friends, join groups, or create public pages in 140 languages, reaching people all over the world. The Chinese government is sure to want a Facebook post written in any languages about, say, Tibetan independence, blocked in China.

To do so, Facebook might borrow the playbook of a Chinese competitor.

While WeChat is accessible to users all over the world, it runs differently inside and outside China. People or organizations anywhere can register for Chinese official accounts (roughly analogous to public Facebook pages), where they’re screened for sensitive content and visible to anyone. Separate official accounts exist for people located outside of China. Data from overseas official accounts are stored on overseas servers, and not subject to the same censorship policies. They’re also not accessible to WeChat users who have registered from within China.

Facebook could employ similar tactics, in effect creating a “Great Firewall” from within Facebook itself. Chinese users might still be able to friend individuals outside the country, but be restricted from seeing some of their posts or creating pages the whole world could see. Likewise, foreign companies that create public pages might have to create separate ones for Chinese users.

Facebook did not respond to requests for comment about the company’s plans in China.

As Zuckerberg continues to ramp up his publicity stunts, the Chinese authorities seem increasingly receptive to them. Tellingly, they’ve called for negative comments about Zuckerberg to be removed from social media. That’s because a censored, altered, government-friendly version of Facebook in China would mark a major policy victory for China’s internet authorities. It’s exactly what they want.

Xi Jinping has been a strong advocate of the notion of “internet sovereignty,”—meaning that national governments have right to police the internet as they see fit, in contrast to the Western notion that the information on the internet should mostly flow across national borders freely. Already, Facebook blocks thousands of post and pictures a year deemed too “sensitive” by other governments so the social media giant isn’t blocked in these countries.

But China’s demands will make Facebook’s complicit in “internet sovereignty” to a much greater degree.

When authorities demand Facebook share information about the location or posts of an activist, a journalist, an outspoken scientist, or a local whistleblower, for example, Facebook will have to comply, or risk being blocked. And when that activist or journalist is punished, Facebook will be responsible.

Zuckerberg will put his thesis that the benefits of “connecting everybody” outweigh the costs of complying with oppressive regimes to the ultimate test.