The New Terrorist Training Ground

Last year, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb did something no other modern terrorist group has: conquered a broad swath of a sovereign country—Mali. Since then, despite French intervention, northern Mali has become a jihadist front, with Islamist militants flowing in from around the world. While America remains focused on threats from the Middle East and South Asia, the new face of terror is likely to be African.

Gao, the largest city in northern Mali, is a place of extremes. It’s a sprawl of one- and two-story mud-brick houses that lack power lines and running water, but it’s also home to the garish, McMansion-style estates of Cocainebougou, or “Cocaine Town,” a deserted neighborhood that once belonged to Arab drug lords who controlled the region’s smuggling routes for hashish and cocaine but fled, fearing reprisals from local citizens who blamed them for the Islamist invasion. The city has few high schools and no universities, but many of Mali’s leading guitarists and percussionists learned their craft in Gao’s decades-old youth orchestras; it is a proudly secular city that also houses the Tomb of Askia, one of the oldest mosques in Africa, built in the 15th century to honor a regional ruler. Gao was for centuries best known as the capital of the ancient Songhai Empire, which once controlled a region larger than present-day Mali. In the summer of last year, an al‑Qaeda affiliate known as AQIM, for “al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb,” took over Gao and made it the capital of the rump state the group created after forcing the Malian army out of the north. Months earlier, the Tuareg, a separatist minority long bent on independence, had laid the groundwork for AQIM and its Islamist allies when they captured the city. When I visited northern Mali in March of this year, a black-metal billboard the extremists had erected on the main road leading into the city was still welcoming visitors to the “Islamic City of Gao.”

French air and ground forces reconquered the north this past January, bringing the region back under the nominal control of Mali’s fragile central government. Camouflage pickup trucks full of Malian soldiers now rumble down Gao’s otherwise empty streets, and a handful of small bars and restaurants have reopened. Castel and other Malian beers, strictly forbidden under the Islamists, are freely available, though they’re usually served warm because of the city’s frequent power outages. I walked through the main bazaar one afternoon with Baba Douglass, an affable, rotund man who works as a top adviser to Gao’s mayor, Sadou Diallo. Teenagers hawked Nokia cellphones and women in brightly colored blue dresses and head scarves peddled warm bread and cake, calling out prices as we passed. Douglass pointed to a pair of canary-yellow bulldozers looming over a fenced-off expanse of dirt and stone. “That’s where the new central market building is going,” he told me. “If things stay quiet, it will be open by the end of the year.”

That’s a big if. Mali’s central government now runs Gao, but many locals believe that the jihadists who controlled the city last year have melted away into the surrounding countryside, where they are waiting out the French. France launched its military campaign on January 11 with a series of air strikes on insurgent targets. Thousands of French ground troops poured into the country later that month and began pushing north. At the peak of the campaign, more than 4,000 French soldiers were in Mali, but the French military has announced plans to withdraw about 3,000 of them by the end of the year. Paris will pull out the remaining troops next year, leaving behind an unspecified number of special forces and trainers to mentor the Malian security forces, and will also support a new United Nations peacekeeping force of 12,600 troops drawn from other African countries. But many ordinary Malians still fear that their country’s armed forces won’t be able to fill the void.

After saying goodbye to Douglass, I made my way through the remains of a walled compound that once housed the mayor’s offices. About a dozen militants had snuck in days before and lobbed grenades at a convoy of passing Malian military vehicles, kicking off a fierce gun battle that raged for more than seven hours. French forces relieved the overmatched Malian soldiers and eventually killed all the attackers, but the fighting left the compound in ruins, two of its yellow walls reduced to piles of scorched concrete and rebar. The ground was littered with spent cartridges, scraps of clothing, and razor-sharp shrapnel. The compound’s custodian, Hasan Haidara, led me into a garage and pointed to a splotch on the floor that looked like brown paint. “Blood from one of the jihadis,” he told me. Haidara, who’d been trapped in the compound during the attack, said several of the fighters were Arabs. “They were not from Mali,” he said emphatically. “They were not from here.”

I heard a similar refrain from an array of Malian and American security officials. Gao’s central jail is housed in a defunct two-story health clinic a short drive from the mayor’s compound. When I visited, the warden, Captain Ballo Banfa, told me that many of his prisoners had come from Algeria, Tunisia, Nigeria, and other neighboring African countries. Captain Ibrahim Sanogo, an intelligence officer at a nearby Malian military base, told me that he’d listened in on radio conversations between rebels speaking English, Fulani, and Hausa, three of the primary languages of neighboring Nigeria, and personally interrogated captured fighters from Burkina Faso and Chad. France captured two of its own citizens allegedly fighting alongside the Islamists in northern Mali and is holding them on terrorism charges. U.S. officials say foreign fighters from across Africa have been flowing into Mali to earn their jihadist bona fides and gain tactical experience battling a well-armed Western military. “Northern Mali has become a jihad front,” said a U.S. official familiar with the region, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “People think of northern Mali like they thought of Chechnya in the late ’90s—as someplace where you can go and do your part to restore the caliphate.”

The foreign militants battling Malian and French troops across northern Mali are part of a little-noticed but hugely important shift. American policy makers have long treated the Middle East and South Asia as the main battlegrounds of the war on terror, but those regions are quickly being joined by Africa, which is now home to some of the largest and most active Islamist militias in the world. The Islamist extremist group Boko Haram used a massive car bomb to demolish a UN compound in Nigeria in 2011, leaving at least 23 people dead, and has killed hundreds of other Nigerian citizens and security personnel over the past two years as it has fought to impose Sharia law in the oil-rich state. The Somali militia known as al-Shabaab has carried out suicide bombings throughout the beleaguered capital of Mogadishu and in neighboring countries like Uganda. Radicalized Africans have been involved in terror plots in the continental United States, taking advantage of the fact that they typically attract less scrutiny than Arabs or Pakistanis. The militant who tried to down a packed Northwest Airlines flight bound for Detroit on Christmas Day 2009, for instance, was a Nigerian named Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab.

The Islamist groups fighting in Mali pose a particularly dangerous threat. AQIM has already accomplished something no other al-Qaeda franchise has ever been able to pull off: conquering and governing a broad swath of a sovereign country, then using it as a base to plot sophisticated attacks outside its borders. Libyan fighters trained by AQIM took part in last September’s attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya, which killed Ambassador Christopher Stevens and three other Americans, according to another U.S. official familiar with the region, who spoke on condition of anonymity. Mokhtar Belmokhtar, at the time the top al-Qaeda commander in northern Mali, also helped the al‑Qaeda affiliate in Algeria organize the conquest of a sprawling natural-gas facility there earlier this year; at least 37 hostages, including three Americans, were killed when Algerian special forces retook the compound. In late May, Islamist fighters loyal to Belmokhtar attacked a French-owned uranium mine in northern Niger and a nearby army outpost, killing nearly two dozen Nigerian soldiers. Belmokhtar, who is still at large, and AQIM have publicly promised to carry out attacks in France in retaliation for the country’s intervention in northern Mali.

That is far from an empty threat. Mary Beth Leonard, the American ambassador to Mali, told me during a March interview in her tidy embassy office, on a small, tree-lined street in the capital city of Bamako, that the U.S. believes a Malian terror attack in Europe is a real possibility. Leonard noted that a significant number of Malians live within France’s borders, which means Malian radicals loyal to Belmokhtar or other Islamist commanders could potentially evade scrutiny amid the flow of Africans traveling between the two countries. “The most proximate fear is that the threat could reach the European homeland,” Leonard told me. Citizens of any European Union country can travel to other EU nations without a visa, and Leonard worries that Malian jihadists with French passports could spread across the continent to strike European targets, as well as American embassies, schools, and military bases.

American officials also fear that Mali’s 10 months as a de facto Islamist state allowed Belmokhtar and other local militants to operate rudimentary training camps where radicals from across Africa could train alongside one another and share tactics for building stronger bombs and mounting more-effective ambushes and attacks. A U.S. official who closely monitors Mali told me that Boko Haram had sent new recruits from Nigeria into Mali to improve their battlefield skills. Many of those hardened fighters have since returned, bolstering Boko Haram’s ranks as it intensifies its fight against the regime of Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan in an effort to establish Sharia law. Amanda Dory, the Pentagon’s deputy assistant secretary of defense for Africa, told me that Islamists from countries like Tunisia and Algeria have also started returning home from Mali, taking their new experience fighting Western militaries with them.

Fears about Africa’s emergence as a terror haven are unlikely to subside anytime soon. Africa’s Islamists are able to take advantage of the fact that many of the continent’s countries have porous borders; weak and corrupt central governments; undertrained and underequipped militaries; flourishing drug trades that provide a steady source of income; and vast, lawless spaces that are so large—and so far away from major American military bases like those in the Middle East and Afghanistan—that it would be difficult for the U.S. to mount effective counterterror efforts even if the war-weary Obama administration chose to do so. Those are precisely the reasons (along with a trove of Libyan weapons) Islamists were able to conquer northern Mali and use it as a base for planning the strikes on the uranium mine in Niger and the natural-gas plant in Algeria. Those are also the reasons American officials worry that a successful terror attack in the U.S. or Europe planned in Africa and carried out by African extremists is only a matter of time. The new face of militant Islam, in other words, is likely to be an African one.

Mali’s fall is a story of a decade of American missteps—and a cautionary tale of what could happen if the U.S. doesn’t begin devoting more attention and resources to combating Africa’s growing terrorist threat. President Obama nodded to those dangers in May in a major speech on the future of the war on terror. “What we’ve seen is the emergence of various al‑Qaeda affiliates,” he said. “From Yemen to Iraq, from Somalia to North Africa, the threat today is more diffuse.” Still, Obama cautioned that he wanted U.S. troops to focus on helping other countries battle the militants operating inside their borders, not to take unilateral action against the extremists. That approach would be in keeping with Washington’s recent policy toward the region. Successive presidential administrations failed to take stronger action against the militants who eventually conquered northern Mali, for three main reasons: bitter bureaucratic infighting between the Pentagon and the State Department; a mistaken belief that Washington’s putative Malian allies were committed to cracking down on their country’s militants; and a fundamental misreading of how much ordinary Malians had come to despise Amadou Toumani Touré.

Touré, a former army officer, took power in 1991 after helping oust the country’s then-president, Moussa Traoré, and won international acclaim for leading a successful effort to draft a new constitution and clear the way for nationwide elections. Touré, who is universally known as ATT, transferred control of the country to Mali’s first freely elected leader in 1992 and resumed his military career. He put himself forward as a presidential candidate in 2002, after retiring from the army, and was elected by a wide margin. He handily won reelection in 2007 and later promised to step down at the end of his second term, as mandated by the constitution he had helped write. The U.S., which saw Touré as a rare African leader with a genuine commitment to democracy, showered Mali with $728 million in aid, beginning in 2008 and continuing until its rules for providing aid prevented it from doing so.

That was on March 22, 2012, when ATT was ousted in a military coup, just weeks before his second and final term was slated to end. The Touré government had become wildly unpopular because of its blatant corruption, with the president’s relatives and political allies building massive mansions in Bamako while buying property in Dubai and other foreign cities, according to Malian press reports and a senior Malian lawmaker. Malian officials say that Touré also turned a blind eye to the country’s burgeoning drug trade, apparently concluding—mistakenly— that allowing the north to reap tens of millions in drug proceeds each year could prevent another uprising by members of the country’s independence-minded Tuareg minority. “The politicians who were close to ATT didn’t even try to hide all the money they were stealing,” Siaka Traoré, the deputy head of the Malian parliament’s defense committee, told me. “A colleague of mine built a house in the north that was so big, even Barack Obama couldn’t afford a house like it.”

The widespread corruption wasn’t what drove Touré from power, though. The coup was instead motivated by the military’s fury over what they saw as the leader’s weak and ineffectual response to a rebellion in the north by the Tuareg, a light-skinned Berber people who have been agitating for the creation of an independent state for more than 50 years. The Malian army had managed to put down previous Tuareg uprisings, in 1962, 1990, and 2007, but the uprising that began in full in February 2012 was very different. Thousands of young Tuareg men had served in the Libyan military during the long reign of Muammar Qaddafi. When he was deposed in 2011, the Tuareg fighters returned to Mali with mortars, anti-tank missiles, and other advanced weaponry that they’d looted from his armories. The Tuareg also had important allies: hundreds of Islamist fighters from AQIM, the local al-Qaeda affiliate; and a pair of newer extremist groups, Ansar Dine and the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa, known by its French initials, MUJAO.

Senior Malian military commanders began angling for a fight with the Tuareg and their Islamist partners when Ansar Dine overran an army base in the northern city of Aguelhok in early March 2012 and killed dozens of captured soldiers. The Islamists released photos showing rows of dead troops lying facedown in the dirt, hands tied behind their backs. The incident didn’t attract much attention outside Mali, but many army officers, primarily based in Bamako, saw it as the final proof that ATT wasn’t giving the army the resources it needed to properly combat the insurgency.

“We had 120 men in a dangerous place who didn’t have enough weapons, fuel, and ammunition, and the government hadn’t purchased helicopters that had the range to fly reinforcements to the base,” Colonel Adama Dembélé, the vice chief of the Malian army, told me in his Bamako office. “There was a feeling of shame that we didn’t have the means to protect our own soldiers, and there was a feeling of anger at ATT.”

Less than a month after the massacre, a handful of Malian officers decided that they’d had enough. A military junta led by a young captain named Amadou Sanogo deposed ATT, who went into exile in Senegal; suspended the constitution; and promised that it would take on, and defeat, the rebels who were gradually conquering the north. The coup caught the U.S. government off guard. “We were surprised,” a senior State Department official told me. Still, he added, “no one could have predicted the multiple crises that would hit Mali simultaneously and the public disappointment in ATT with elections only two months away.”

Sanogo, Mali’s new leader, ordered reinforcements to the north, but he badly underestimated the strength of the Tuareg and the Islamists. The rebels routed the Malian military, which was in disarray after the coup, and conquered Gao, Timbuktu, and Kidal—the north’s largest cities—in three days. By early April, Mali had effectively been cut in two, with the remnants of the Malian military fleeing south, leaving the north to the rebels. Belmokhtar, AQIM’s top commander at the time, publicly predicted that his forces would soon control all of Mali.

Belmokhtar was far from unknown to the U.S. military and intelligence officials who were watching Mali’s dismemberment with mounting alarm. As a teenager in the late 1980s, Belmokhtar had traveled from his native Algeria to Afghanistan to wage jihad. He lost his left eye, by his account in the fighting—a badge of honor he wore with pride. In 1993, he returned to Algeria with a new nickname—Belaouar, or “the one-eyed”—and a new target. The country’s French-backed government was locked in a bloody civil war with a loose alliance of Islamist groups, and Belmokhtar helped plan and carry out dozens of attacks against Algerian security personnel and citizens deemed loyal to the regime. By 2003, Belmokhtar was a senior leader of the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat, a violent group operating throughout West Africa. U.S. officials saw him as a growing threat to Algeria and other allies throughout the region. The question was, what to do about it?

General Charles “Chuck” Wald thought he knew the answer. Wald, a stocky, blunt-talking officer who’d been drafted by the Atlanta Falcons as an H‑back before he joined the Air Force in 1971, was the deputy commander of the Pentagon’s European Command, which at the time had responsibility for Africa. In 2003, U.S. surveillance spotted Belmokhtar at a militant training camp in a remote patch of desert just south of the Algerian border. The military had been searching for him for some time, and Wald thought this was the best chance to take him out.

Wald and his staff developed a range of options for trying to kill Belmokhtar while they had a fix on his hiding place in northern Mali. One of the highly classified plans called for sending in a B‑52 bomber to obliterate the militant outpost; another would have used air strikes by F‑16s to destroy the encampment; and a third proposed flying in a team of elite Special Operations forces to capture or kill Belmokhtar on the ground. When I spoke to Wald recently, he told me that he and his command team were never serious about using a B‑52 strike, and had put the idea forward as a “throwaway” in the internal government negotiations. His preferred option was to send in a team of U.S. commandos, which could have been done without attracting much public attention. Regardless of the method, Wald was adamant that the U.S. needed to take out Belmokhtar while it could. “We finally had this guy in our sights,” Wald, who has since retired, said. “I kept arguing that we needed to take the shot before he disappeared again.”

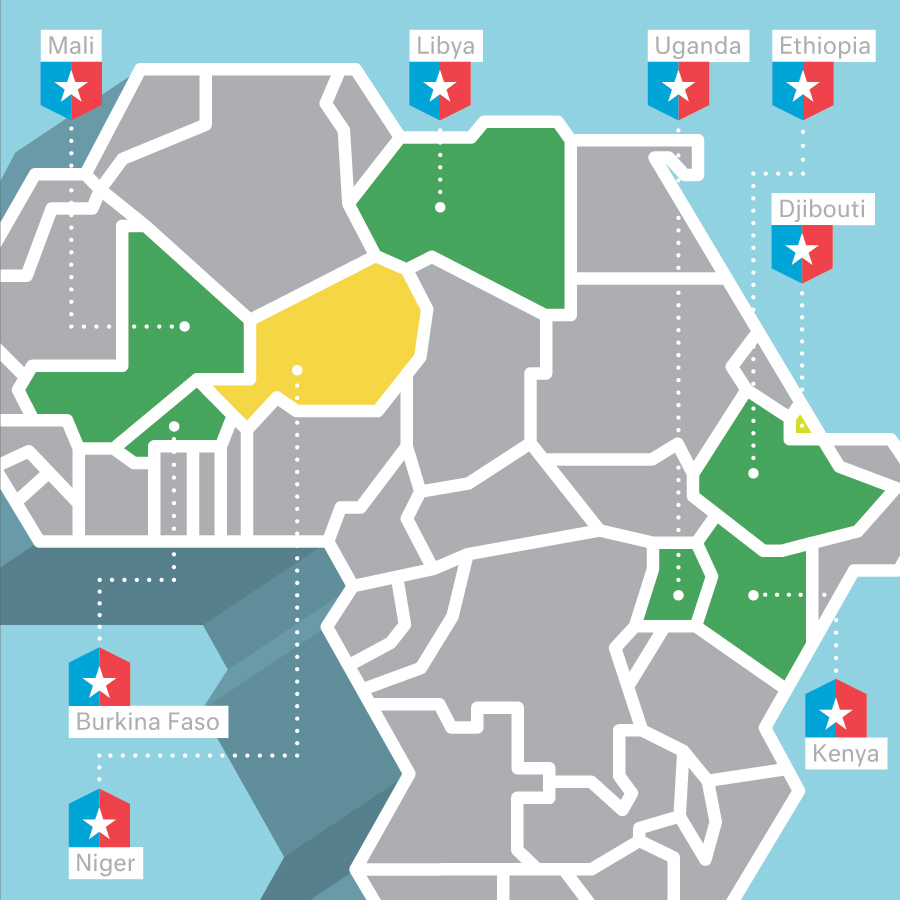

The U.S. military is expanding its presence across northern Africa. Shown here: Djibouti, which hosts Camp Lemonnier, the only official U.S. base on the continent; Niger, where the U.S. recently sent military personnel and drones to support the French mission in neighboring Mal; and the countries where the U.S. is reported to field troops, launch drones from, or both. (Map by James Bamford)

Vicki Huddleston, the U.S. ambassador to Mali at the time, felt very differently, and argued for patience during a series of tense discussions. She and her team said that the intelligence marshaled by Wald and his supporters was far from conclusive as to who exactly had been found. The U.S., she said, risked carrying out a politically sensitive operation inside a sovereign country only to find out that the target wasn’t there. And even if it had the right man, Huddleston said, she didn’t believe there was enough evidence against Belmokhtar to warrant a strike. “We didn’t even know who Belmokhtar was,” she told me. “All we knew at the time was that he was an Algerian cigarette smuggler. As far as I know, there’s no legitimacy to unilaterally killing Algerian cigarette smugglers.” Huddleston argued that taking out Belmokhtar would set a dangerous precedent, by killing someone who had not yet shown the inclination or the capacity to attack the United States. African countries were particularly sensitive about Western military operations inside their borders, and Huddleston feared that a high-profile American air strike would turn public opinion against the U.S. “Wald seemed to think you can carry out kinetic strikes without cost,” she told me. “But they can radicalize people on the ground. They do have a cost.”

Huddleston says that because the ambassador was required to sign off on any military operations, she was able to veto the strike. Belmokhtar, as Wald feared, disappeared into the vastness of northern Mali and the other countries of the Sahel. More than a decade later, the wounds are still raw. Wald derides the former ambassador as “Field Marshal Huddleston” and says she should have deferred to the military about the strike. “It was a giant missed opportunity,” he says.

Belmokhtar soon emerged as one of West Africa’s most dangerous Islamist militants. In 2005, his forces began carrying out regular strikes in Mauritania, just west of Mali, including a sophisticated assault on a military base that killed 15 soldiers and allowed his fighters to make off with huge quantities of weapons and ammunition. In 2006, Belmokhtar and the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat’s other senior leaders formally pledged allegiance to Osama bin Laden and changed the group’s name to al‑Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. The following year, the newly christened group stole a page from bin Laden’s playbook and bombed a United Nations building and a government compound just outside of Algiers, killing at least 60 people. It kidnapped dozens of Westerners, including a pair of Canadian diplomats, and collected tens of millions of dollars in ransom. The U.S. officials nervously tracking AQIM’s growth felt that it had become the strongest, best-funded, and best-organized Islamist organization in the Sahel. Washington had given Touré, still Mali’s president at the time, hundreds of millions of dollars in aid, largely to encourage him to take on AQIM. With the group growing steadily more dangerous, the Obama administration decided it was time to press Touré to mount a serious and sustained push against the militants.

On June 10, 2009, then-Ambassador Gillian Milovanovic met with Touré for an hour to deliver that message personally. She told him that AQIM’s continued operation in northern Mali was tarnishing the country’s image in the West and threatening to erode the gains Mali had made since becoming a democracy in 1992, according to a summary of the meeting in a confidential State Department cable released by WikiLeaks. Touré, according to the cable, “repeatedly blamed Algeria, Niger, and Mauritania for … abdicating their responsibility for policing the Sahel to an under-manned, under-equipped and under-trained Malian military,” but promised to take a firmer stand against AQIM. The ambassador left the meeting convinced that Touré was finally serious about confronting the group. “We believe that we can also count on President Touré’s good faith efforts to counter AQIM, despite Mali’s well-known military and financial limits,” a U.S. diplomat wrote in the cable. “ATT is ready to do something about this.”

It was a serious miscalculation. Touré never mounted a concerted push against AQIM, and instead used military equipment provided by the U.S. to crack down on the Tuareg separatists who had been rebelling against the Malian central government more or less continuously for decades. “Over time we began to realize that the ATT government was focused not on AQIM as a threat but rather on Tuaregs in the north,” a senior defense official at the Pentagon told me. “He saw a political threat and a security threat but not the kind of counterterrorism threat that we were focused on. I think that kind of mismatch is part of what was starting to unravel the partnership on [counterterrorism] when the coup happened.”

U.S. officials similarly misjudged Iyad Ag Ghali, the Tuareg extremist who would later found Ansar Dine, AQIM’s main ally in its conquest of northern Mali. During the 2007 Tuareg rebellion, Ag Ghali had helped mediate between Touré and the Tuareg independence fighters in the north, earning a reputation as a relative moderate. On May 30, 2007, Ag Ghali sat down with American Ambassador Terence McCulley, Huddleston’s successor (now the ambassador to Nigeria), in his office at the embassy to request U.S. assistance for “targeted special operations” against AQIM, a group Ag Ghali described as an extremist organization with little to no support among the residents of northern Mali. A confidential cable made public by WikiLeaks described Ag Ghali as “soft-spoken and reserved” and said he “showed nothing of the cold-blooded warrior persona created by the Malian press.” He told McCulley that he was planning to leave Mali for a diplomatic posting in either Saudi Arabia or Egypt because “he was tired of the problems in the north,” according to the document. Touré had offered him the job because of his role as a mediator between the government and the Tuareg.

Ag Ghali left for Riyadh a few months later, but he didn’t last long. Rudolph Atallah, the Pentagon’s top counterterrorism official for Africa from 2003 through 2009, told me recently that Saudi Arabian officials declared Ag Ghali persona non grata in 2008, and kicked him out for maintaining close relationships with unspecified Islamist radicals and clerics. (A Saudi official in Washington declined to comment.) Atallah believes that Ag Ghali’s time in Saudi Arabia was the final step in his evolution from a relatively moderate Muslim who was known to drink and make regular visits to Paris into a full-blown believer in violent jihad against the West. “I don’t think he was flipped there,” Atallah told me. “I think he’d already begun to change. But the fact that he was pushed out of Saudi Arabia for his ties to these groups certainly shows that his personal beliefs had begun to match up in a very tangible way with extremist ideology and behavior.” Ag Ghali periodically surfaced in Mali and Pakistan after his time in Saudi Arabia, but by 2009 he, like Belmokhtar, had largely disappeared from public view.

Both men had reemerged by early 2012 at the forefront of the Islamist forces that quickly pushed the ill-equipped and undermanned Malian army out of the northern half of the country. The Malian troops who fled south left behind pickup trucks, armored vehicles, weapons, ammunition, radios, and equipment. Much of the equipment had been donated by the U.S. for use against the Islamists. Instead the Islamists used the weapons and trucks to cement their control of Timbuktu, Gao, and the region’s other cities and towns.

The United States is racing to expand its military and intelligence capabilities in Africa, taking advantage of the fact that some governments that were once reluctant to house American military facilities on their soil are so rattled by the unrest in Mali, Somalia, and other African nations that they now welcome U.S. personnel with open arms. In March, The Washington Post reported that the United States opened a new drone base in Niamey, the capital of Niger, to complement existing facilities in Ethiopia and Djibouti. (The U.S. government denies that such a base exists.) According to the article, the Predator drones flying out of Niger are currently being used to feed surveillance footage to French and African troops on the ground in Mali, but the aircraft could easily be outfitted with missiles if the administration chose to adopt a more muscular approach to the conflict. Niger’s president, Issoufou Mahamadou, told The Post that his country needed the drones because its military was too weak to defend its borders on its own. “We welcome the drones,” he said.

The U.S. drones flying out of a Nigerien airfield near Niamey are assigned to the Pentagon’s Africa Command, or Africom, which is responsible for coordinating all American military activities on the continent (except for those in Egypt) and for carrying out the Obama administration’s strategy for countering the growing Islamist threat in Mali, Somalia, and other countries. Africom was hobbled at the outset by poor leadership, an uncertain mission, and a lack of resources. The Pentagon is now considering whether to eliminate Africom altogether as a cost-cutting measure, according to an August report in Defense News. If it’s abolished, Africom’s current responsibilities would be divvied up between Central Command and European Command. The idea for Africom originated with former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, who saw it as a way of consolidating the U.S. government’s disparate efforts to train individual African militaries. Rumsfeld’s successor, Robert Gates, saw it as a way to strengthen the capabilities of the continent’s emerging democracies, Mali very much included. Gates formally announced its creation in February 2007. Later that month a small military transition team deployed to Stuttgart, Germany, to set up what was supposed to be a temporary headquarters.

U.S. military planners wanted to move Africom to Africa, but many African nations, still haunted by the ghosts of past colonial abuses and not yet threatened by clashes on their own borders, refused to house the new organization. The only country willing to host the new command was Liberia, an isolated and impoverished country that would have presented the military with significant logistical challenges. In February 2008, after a year of fruitless searching, the Pentagon said Africom would remain in Germany, nearly 1,000 miles from the continent it was created to oversee. U.S. Central Command, which has responsibility for the Middle East, Egypt, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, is based in Tampa, Florida, but it has a large forward headquarters in Qatar. One of Africom’s subordinate commands has roughly 4,000 troops stationed at Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti: Africom’s sole significant physical presence in Africa.

Africom’s biggest shortcoming is that it is a command in name only: it has no troops, tanks, or aircraft of its own. The 2011 U.S. military intervention in Libya was the most important moment in Africom’s history, but General Carter Ham, then the commander of Africom, had to borrow aircraft and helicopters from European Command because he had none of his own. Africom controls the drones flying over Mali from the bases in Niger and other nearby countries. But any future U.S. intervention in Mali, Somalia, or other emerging terror sanctuaries on the continent—whether via air strikes, which are a possibility, or the deployment of American combat troops, which appears highly unlikely—would require Africom’s new commander, General David Rodriguez, to ask other parts of the military for aircraft, armaments, and troops.

In Mali, the U.S. is relying on the same military that fled the north in the spring of 2012 to hold the line after the French withdraw their troops later this year. The confidence seems misplaced. The Malian armed forces have about 7,000 troops, many with little to no combat training. Malian army commanders in the north are so concerned that Islamists will use purloined uniforms to slip onto their bases to mount new attacks that they’ve given loyalist soldiers swaths of red fabric to attach to their uniforms. When I asked one officer what would prevent the Islamists from simply buying identical bits of fabric, he shrugged and told me, “The future of this place is in God’s hands.”

It’s also in the hands of Colonel Didier Dacko, a fluent English speaker who serves as the Malian army’s top commander in the north and faces the difficult task of maintaining control of the region until the French withdraw their troops. Maintaining control is a job Dacko has spent his entire military career preparing for.

“The bomb hit me right here,” Dacko told me one afternoon in March, pointing to his left leg with a lit cigarette, one of the 20 or so he’d smoked since we’d driven away from his base outside Gao two hours earlier. In 2008, Dacko had heard rumors that armed Tuareg rebels were massing in a savanna-like swath of hills and valleys alongside the nearby Niger River, and he wanted to find and hit them before they could find and hit him. “I had some broken bones, but nothing too bad. I can still walk with both feet. Speaking frankly, I was surprised it hadn’t happened sooner.” Dacko was understating the severity of the injuries he’d suffered when his pickup truck rolled over a buried land mine near Mali’s northern border with Algeria; the explosion nearly severed his leg, and one of Dacko’s aides later told me that the commander almost died from blood loss.

Dacko is a rarity in the Malian army: a combat-hardened commander respected by American and French officers, who disparage many of Dacko’s colleagues as incompetent, cowardly, or in secret collaboration with the rebels. When the broken and demoralized remnants of the Malian army fled south last year after the Islamists swept through the north, Dacko was the one who formed a last-ditch defensive line outside Mopti, the final major city before the capital of Bamako. If Mopti had fallen, the militants would have had a clear path to Bamako. Dacko held the Islamists at bay until French forces arrived and began pushing the militants back north.

Dacko, a thin man whose wispy gray mustache gives him a faint resemblance to Attorney General Eric Holder, was born in the southern-Malian region of Sikasso in 1967. His father had fought in Indochina and Algeria for the French, and Dacko grew up hearing stories about the glories of combat and the unique bonds between fighting men. Still, he had vastly different ambitions. “As a child, I wanted to be a singer,” he told me, laughing over a late-night beer. “Then I realized I didn’t have a particularly good voice.”

Dacko joined the military at age 21, after studying electrical engineering at the University of Bamako. His first posting was in Kidal, the northernmost city in Mali; Dacko has spent his entire military career either fighting in northern Mali or trying to prevent others from having to do so. The bomb that nearly killed him went off outside Kidal, just as Dacko’s men were defeating the last of the rebelling Tuareg forces. He spent much of 2008 recovering from his injuries and then headed to Washington’s National Defense University in 2009 for a yearlong academic posting.

Dacko devoted his time at the school to studying counterinsurgency theory, which argues that troops looking to defeat a homegrown uprising need to gradually convince ordinary citizens to back the government, rather than the rebels, by providing them with security, jobs, and improved access to schools and hospitals. He devoured the writings of David Galula and T. E. Lawrence, the intellectual forefathers of counterinsurgency, and decided that their ideas about combating rebellions in Algeria and the Middle East held lessons for his country as well.

“What I took away was that in dealing with insurgencies, the most important thing is to work with the population and win them over without using too much force,” he told me one night over a shared plate of red rice, eggplant, and lamb. “We need the Tuareg on our side, or at least not as our enemies. We can’t win over the jihadis; we need to crush them. But we can’t do it if we’re fighting all of the Tuareg as well.”

In May 2010, Dacko distilled his thinking into a 62-page thesis for NDU called “How to Improve the Security Situation in Northern Mali.” He argued that the series of Tuareg rebellions over the previous 50 years had cleared the way for Islamist groups to move into northern Mali and use it as a haven to plan and carry out strikes in Algeria and Mauritania while developing the capability to eventually conduct terror attacks in Europe as well. Given enough time, he wrote, al‑Qaeda would move into the region. “It is possible that northern Mali could become the next Afghanistan, if the security situation is not managed at the right time,” he wrote.

Dacko is now the man most directly responsible for making sure that doesn’t happen. He lives and works out of a compound of crumbling one-story buildings in Gosi, a tiny town about an hour from Gao. It has no electricity or running water; Dacko and his men use markers to chart the movement of French and Malian troops on a laminated map taped to a stucco wall. During my night at the base, an aide carried out a small TV, plugged it into a generator, and tuned it to a French news channel. Dacko spent an hour watching video footage of a battle raging less than 50 miles away before going to sleep on a cot outside his headquarters building.

In his current post, Dacko is putting his thinking about counterinsurgency into practice. One afternoon, he and his men got into body armor and grabbed AK-47 assault rifles before leaving the compound in search of the Tuareg fighters they’d been told were hiding nearby. Dacko’s men made their way over steep hills and through dense patches of trees, but they couldn’t find any trace of the militants. On their way back, Dacko spotted the distinctive round tents of the Bella, a group of black nomads who are routinely enslaved by the Tuareg and other ethnic groups. Goats were tied to trees, watched over by young boys with wooden sticks. Herds of camels ambled in the distance, lazily chomping on mouthfuls of mottled green grass.

Dacko stepped out of his truck, flanked by a pair of soldiers, and asked the first Bella man he saw to direct him to the tribal elder. A man of about 60 emerged from one of the tents, his face largely obscured by a black-and-white scarf. Dacko extended his hand and asked whether any militants had been seen or heard nearby. The man shook his head, avoiding eye contact. Dacko told him to visit the Gosi base if he or anyone in his village spotted fighters or needed medical attention, food, or water. The man nodded and walked back inside the tent. He hadn’t said a single word the entire time. “I’ll never hear from them,” Dacko told me on the drive back. “They’re too scared. That means there are probably jihadis nearby.” He radioed one of his officers and told him to lead another patrol at sunrise.

Dacko’s offers of food and water come straight from his NDU thesis, which said that the Malian government could dislodge the militants only if they won over local residents by providing educational and economic opportunities while simultaneously conducting targeted strikes against the Islamists. Done correctly, Dacko predicted, this strategy could clear the militants out of the region within three years. “I didn’t see this current war coming,” he told me one night. “I saw why the north was ripe for another war, but I didn’t know it would come so soon, or with so much force. I thought we were stronger and they were weaker.”

The U.S. didn’t see the war coming either, and the Islamists’ conquest of the north put the White House in a bind. Washington had been tracking AQIM for years and knew that it posed a growing threat to American and Western interests across Africa, but wasn’t sure how to respond. In 2009, the White House had considered, and by most reports rejected, a covert plan code-named “Oasis Enabler,” which would have cleared the way for elite U.S. commandos to take part in counterterrorism missions inside Mali. The U.S. presence there was instead limited to a handful of Special Forces teams charged with training the Malian military and providing Bamako with satellite imagery of rebel encampments.

Washington had provided the Touré government with more than $100 million a year in foreign aid and military assistance. But under laws approved by Congress every year for decades, the U.S. had to halt all its aid programs and withdraw all its military personnel when Touré was deposed in the March 2012 military coup. That meant the United States had no troops on the ground as Mali, a close ally, was being torn apart by fighters from a terrorist group the Pentagon had been tracking for nearly a decade.

The American withdrawal had left Dacko baffled and angry. “The coup happens, we’re weaker than ever, and then you pull your aid?” he said. “We’re fighting the same enemies. Why should a coup be more important than defeating AQIM? It’s your enemy just as much as it’s ours.”

Mali held democratic elections this summer. Washington plans to reopen the aid spigot and dispatch more American military trainers as soon as Mali’s generals hand back control of the country. Still, the earlier aid cutoff meant that the U.S. was a bystander when the last major battle of the war took place, this past January, in Konna, a small town about 30 miles from Dacko’s makeshift headquarters in Mopti.

The battle began with the launch of Operation Serval, a muscular French air-and-ground assault on Islamist targets across northern Mali. French air strikes on January 11 destroyed a militant command post and several armored vehicles just outside Konna, killing dozens of fighters and pushing the survivors out of the town. French troops quickly conquered Gao, Timbuktu, and the rest of the north’s major cities. By the end of January, northern Mali had been brought back under the control of the Malian government.

I passed through Konna on my way to Gao, stopping to walk through a deserted compound that had once served as an extremist base. The ocher outside walls were pocked with bullet holes, and the half-dozen Islamist armored vehicles and jeeps closest to the main road had been reduced to blackened, melted husks. The remains of a trio of Toyota pickup trucks littered the back of the property; the owner’s manual for one of the trucks lay on the ground, opened to a page about how to operate the vehicle’s stereo system. The extremists had fled so quickly that discarded shirts and pants littered the courtyard, rustling in the slight breeze. They don’t appear to have gone very far: on March 31, a week after I left Konna, a buried bomb killed two Malian soldiers in Gao. Suicide bombers hit Timbuktu and Kidal in the following weeks. U.S. and Malian officials expect more strikes later this year as France withdraws.

Timbuktu, of course, isn’t Washington, D.C., and Kidal isn’t New York City. AQIM and its allies have hit U.S. targets in Libya and Algeria, but American officials believe that Mali’s Islamists aren’t yet capable of carrying out attacks in Europe or the U.S. “I would say that at this point it’s aspirational,” Amanda Dory, the Pentagon Africa official, told me. Still, she cautioned that Africa contained an array of potential militant targets. “If you are an American business operating in the region, if you’re an American tourist visiting in the region, if you’re an American diplomat working in the region, then there is certainly a threat.”

Washington has spent the past 12 years trying to keep tabs on militant organizations all over the world and decide which ones require immediate attention and which do not. In practice, this has meant that the U.S. is almost always reacting to attacks rather than trying to prevent new ones. In Yemen, for instance, the Obama administration didn’t begin hammering al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula with drone strikes until after the terror group came close to downing a packed passenger jet on Christmas Day and managed to sneak a pair of explosive-laden packages onto a cargo plane bound for Chicago. U.S. strikes have since killed hundreds of alleged militants in Yemen, including at least three American citizens.

“You’ve got to rack and stack these guys,” the U.S. official familiar with the region said. “At some point you have to prioritize and deal with the guys who are punching you in the face first.”

The fundamental question confronting American policy makers is whether AQIM and Africa’s other Islamist groups have become enough of a threat to warrant a concerted U.S. effort to kill their key leaders and destroy their weapons caches and training camps. Doing so would be an extremely difficult task for the U.S. military because of the region’s size and remoteness, but it wouldn’t be impossible. In the end, it would come down to a question of American will, not American capability. Send troops in too soon, and a war-weary public will accuse the administration of jumping the gun. Wait until an attack has taken place, and the same public will lambaste the White House for not taking action earlier. The U.S. has largely ignored Africa’s Islamists for more than a decade. We keep doing so at our own peril.