How Andy Warhol Explains China's Attitudes Toward Chairman Mao

Just as the pop artist diluted and distorted the Chinese leader's image, Mao's legacy has likewise evolved in unexpected ways.

Today was the 120th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s birth, and as the event is celebrated in grand style in Beijing and around China, images of the Chairman are even more ubiquitous than usual this week: A rumored $2.5 billion was invested in celebrations in honor of the figure whose portrait watches over Tiananmen Square and is fastened to the gate of the Forbidden City.

In spite of the birthday celebrations, Mao’s status is marked by a growing ambivalence. Officially, a Communist Party Resolution dictated by Deng Xiaoping, Mao’s successor, declared that Mao was 70 percent right, and 30 percent wrong (with the most grievous errors being the disasters of the Cultural Revolution and the Great Leap Forward). And this mixed legacy makes it hard to pin down exactly what about Mao Party leaders want to celebrate, and what about him they don’t. Who could have anticipated this?

Andy Warhol.

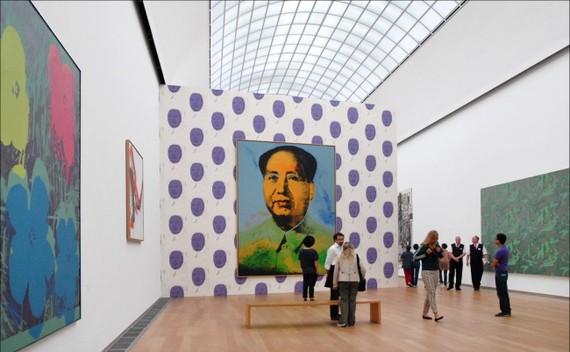

Starting in the early 1970s, the Pop artist made hundreds of images of Mao, using a portrait of the leader from the Little Red Book, a propaganda collection of Mao’s speeches and quotations from the Cultural Revolution, as his template.

Warhol’s Maos are endlessly varied—ferocious, parodic, and beautiful—gestures of paint smeared onto the reproduced outline of the Chinese leader’s head and shoulders. In one huge 1973 canvas, over 14 feet tall, Warhol rouged the Great Helmsman’s cheeks, adorned his eyes with blue pigment, and deepened the red of his lips. With these changes, the mole on Mao’s chin was transfigured into the beauty mark of a French courtesan. Warhol dolled Mao up, on the heroic scale of socialist realism.

But this is only one image of hundreds. The sheer number of Warhol’s screen prints of Mao’s face—at once persistent and reinvented—that captures, with unusual clarity, the attitude of China’s leaders today toward Mao, coloring and recoloring this legacy within an enduring outline.

As with each of his predecessors, Chinese President Xi Jinping regularly harkens back to Mao as a source of both legitimacy and continuity for the Party—in his words today, “forever.” This deference, which the lavish birthday celebrations epitomize, appeases Party conservatives and ordinary Chinese who have not shared in China’s prosperity following market reforms since 1978. Some Western commentators have even termed Xi a “neo-Maoist,” but this impression is difficult to reconcile with the pragmatic, reform-oriented economic policies announced at this year’s Third Plenum.

On the other hand, it’s hard to avoid the impression that Mao would have criticized what China and the CCP have become. Massive inequalities of wealth, opportunity, and power now define Chinese society, and the country’s ideologically mixed “socialist market economy” seems, at street level, to look like thinly-regulated capitalism. Party rule itself is ill, as deeply entrenched corruption festers and many local officials seem indifferent to the needs of ordinary people. Ironically, one of the best examples of this disconnect is the 120-pound gold and jade statue of Mao on display in Shenzhen, a city where there are more migrant laborers (semi-legal and poorly paid) than legal workers.

Mao’s quotations and ideas are repackaged and recolored to fit the needs of the present moment: a “mass line” that forbids the ostentation of the wealthy, and a “rectification” campaign that snipes off the most corrupt former and current officials. (The tension surrounding Mao’s legacy has even come into direct dialogue with Warhol’s images: When Pittsburgh’s Warhol Museum brought a survey show to China earlier this year, officials did not permit his Mao screen prints to appear alongside the rest of his works, because they risked sparking controversy.)

The Party’s use of Mao’s legacy mirrors Warhol’s use of Mao’s face. It is a recurrent and unquestioned outline, an essential structure. But it is precisely because the legacy is so often reinterpreted—and because the image is so often reproduced—that even dramatic changes to its surface do not destroy the underlying core.

In 1982, Warhol finally had the chance to visit China, and see the famous portrait of Mao looming over Tiananmen Square. In a photograph taken by one of his companions, Warhol poses in a crowd of ordinary Chinese people outside the Forbidden City. His arms are straight at his sides, his fingers fidget, and Mao’s face hangs behind him, blurry but still presiding.