In November 1999, on her first visit to Iran, Nancy Matthews arrived at Tehran airport at 3 o’clock in the morning. Susan Koscis followed directly behind her. As far as they knew, they were only the second group of Americans to visit since the hostage crisis.

Koscis had been part of the first group to visit Iran just a few years earlier, and had prepared Nancy as best she could. Both women were working to restart a conversation between Iran and America that had gone cold decades before.

They didn’t have the long Islamic dresses necessary to legally walk out of the airport doors onto the streets of Tehran. Instead, they would wear raincoats until they could buy the proper attire in the morning. The women wrapped scarves around their hair. Physically, they were ready.

Koscis had made the trip a few years earlier through an NGO called Search for Common Ground, when she organised a visit of American wrestlers. Nancy was now planning to find and bring Iranian artists back to the United States for an exhibition. Koscis and Nancy were cultural diplomats.

A group of Iranians sent by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance to greet them approached with gifts: scarves, in case the women forgot their own. Nancy went up to one of the men and stuck out her hand, but he declined. “Men don’t shake hands with women in Iran,” he said.

Standing in the airport in the middle of the night, missing the first social cue in what would become a long adventure, Nancy seemed unprepared for her mission. But she was practising a sophisticated American cultural diplomacy that is not pursued in the current administration of Barack Obama and has not been pursued for several decades. The intellectuals Nancy descends from believed cultural exchange could lay the groundwork for beneficial international agreements, such as the Iran nuclear deal.

Nancy was based at Meridian International, a unique cultural diplomacy nonprofit in Washington DC that receives government grants, including funding from the state department to welcome both high-profile foreigners and exchange students. Its splendid headquarters Meridian House was designed in 1920 by John Russell Pope, best known for the Jefferson Memorial, and is surrounded by three acres of manicured gardens.

By 1999 Nancy, well into life’s second phase, was vice-president of Meridian’s travelling art exhibitions, where she had expanded a fledgling showroom after beginning work there as a consultant in the 1980s.

In one of her early exhibitions, at which Meridian was exhibiting work from the Persian Gulf states and when Nancy was still a consultant, she had an ‘ah-hah’ moment. She realised how much the American people could learn about the Gulf through art if only the exhibition could travel around the US. Nancy made the decision to bring art from different countries to as many American cities as she could.

Over the next 20 years she would exhibit artists’ work from over a dozen countries with difficult relationships with the US, including Vietnam, China and Iran. In addition, she would invite the artists to the opening nights and set up historical and educational trips for them during their visits.

Over time, her reputation grew. Being known as the person who was bringing foreign art to Americans made her a rogue element in Washington at a time when the government saw foreign policy largely as a means to project Americanism around the world.

Nancy raised the funds herself to put on the exhibitions, applying for grants and developing networks to encourage corporate sponsors. Two of her supporters were Exxon Mobil and Coca-Cola. “I must have been persuasive because I was very successful,” she told me in an interview in May at her house in Missoula, Montana. Nancy is now in her 80s, short with brown eyes and golden hair. She speaks in complete, measured sentences, and smiles regularly.

In 1998, two Iranian men walked through Meridian’s majestic oak front doors. They were former UN ambassador Mohammed Mahallati and Amir Zekgroo, professor at Tehran University of Arts. Nancy and her boss, former UN Ambassador Walter Cutler, who before the Revolution had worked as a cultural attaché in Tabriz met with them.

Mahallati and Zekgroo were there to decide whether they would work with Nancy to put on a show that might begin to mend the relationship between their country and the US. In some ways, their proposition was unlikely, as Iran had largely been shut off from the west since its 1979 Revolution. Formal diplomatic ties with the US had been dissolved. On the other hand, a reformist president, Mohammad Khatami, had come to power the previous year and wanted to develop an open foreign policy known as the ‘dialogue of civilisations’.

While putting on an Iranian exhibition in America seemed like a long shot, Nancy and Cutler felt the timing was better than it had been for 20 years, and the atmosphere seemed safe enough to travel to Iran. “We briefly reached out to people to see whether it was a good idea,” says Nancy. “My boss had some networks in Iran because of his work there from before. But we didn’t think about it too much and decided to just go for it”.

Nancy had a long road ahead of her: figuring out how to ship the work from Iran to the US, finding sponsors, Iranian artists, and a partner in the country to help navigate both politics and the art scene. Such challenges are standard in Nancy’s world.

To help recall for me her first trip to Iran, Nancy took out her diary. Heavy evening traffic began at 4pm, with cars sitting bumper to bumper until late. Nancy sat in the back of the car, listening to Persian poetry on the radio, inspecting billboards. One, in particular, stood out. Translated, it read ‘hijab means dignity’.

Later, Nancy was getting ready to leave her hotel. Glancing her own hijab hanging next to the door, she realised with relief she wouldn’t have to do her hair. She simply wrapped the scarf around her head and walked out the door. “The women don’t mind wearing them,” she claimed. “They wear them only outside. When they get inside, they take them off and go about their business”.

I don’t know if Nancy was being naïve or self-censoring in glossing over political problems. It could just be part of the job to accept the cultural norms of the country when she was working there if she was to be successful.

Nancy hopped in a cab, alone. She was feeling bold, being bold. The Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance had invited her to Iran and were, at least for now, her on-the-ground partner. They were showing Nancy historical sites, taking her to university classes, but getting her no closer to contemporary art.

Nancy had a plan. Before she left for Iran, she had read a New York Times article about Sami Azar, new director of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. The museum had been commissioned by lran’s last queen, Farah Diba Pahlavi, two years before the Revolution.

Pahlavi was a Parisian-trained architect and a lover of visual arts and theatre. The museum was built to house and showcase her immense collection of modern art, one of the world’s largest. Its structure blended Persian design elements with modernism, sitting in a green field with an unusual assortment of curved cylinders peeking out from orange sawn stone blocks, arranged to emit natural light into the gallery. But until Sami Azar became the museum’s director in 1997, its collection had been hidden underground.

The driver dropped her in front of the museum, leaving Nancy to search for Azar, as she was showing up cold. “Thank God he was there,” she told me. Azar, tall and thin with large dark eyes and a heart-shaped face, invited her in and they talked for hours. Nancy believes she and Azar quickly recognised a kindred spirit; they were meant to work together. Nancy had found her partner, and guide through Tehran’s contemporary art.

“The museum had tons of staff working there. I became one of them. I showed up every day just like they did and got to work. Nancy needed more curatorial experience, more historical knowledge of Iran’s art scene. “I was looking for artists who showed Iran’s ancient culture. And it wasn’t very hard, because that culture comes through everywhere”.

She was thinking of Persian poetry on the radio, calligraphy used throughout paintings, the frequent references to Iranian identity in conversation. As interested as she was in highlighting Iran’s identity, Nancy was not seeking political art and so her show could have overlooked whomever might have been Iran’s contemporary Andy Warhol.

The museum assigned Nancy a translator from its large staff, and every day the pair left together to meet potential artists for the show. “I never needed to eat lunch because everyone set out cakes and coffee and tea for me,” she said. “We’d talk for hours. I learned a lot about Iran that way”.

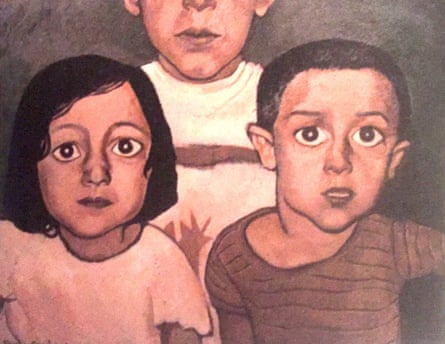

Eventually, after other visits and with the help of the museum, Nancy strung together 54 Iranians artists for her exhibition. She is adamant her selections weren’t censored. Indeed, visual art was subject to little censorship, since government saw the growing art scene as a minor threat, making it the perfect medium for a show like hers – low risk, but potentially with high reward.

A week before the exhibition was due to open at the Queens Library, New York, the Twin Towers in neighbouring Manhattan fell from al-Qaeda attacks. To Nancy’s amazement, the exhibition opened anyway. Sami Azar and the artists came to Washington DC for opening night.

“They were our big success, they were our stars,” Nancy said. “People came in droves. They wrote the most amazing things in the book of comments”. Things like how they couldn’t believe there was so much art in Iran, how beautiful the pieces were, how wonderfully nice the artists were.

The exhibition ran from 2001 until 2003, reaching nine cities across the US and receiving positive coverage ranging from the Los Angeles Times to Associated Press International. In 2002, Bush announced Iran was part of an ‘Axis of Evil’ along with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and North Korea. Nancy remembers a newspaper headline that suggested the exhibition had revealed an ‘Axis of Love’. “They played right off that,” she said.

I asked her how she measures the success of her exhibitions, politically. “Well, you can’t really measure them beyond the turnout and the media coverage but if I didn’t believe they had an effect, I wouldn’t have done them for all of those years”.

There are other, even more indirect ways to gauge effect. According to Nancy, there were two senators’ wives on Meridian’s board in 2001, one of whom was married to Chuck Hagel, who went on to become the defence secretary. Nancy releases a sly smile as she makes the connection. Former Secretary Hagel was open earlier this year in his confidence that Iran and the US would reach agreement over Tehran’s nuclear programme.

Are such connections plausible? Yes, according to Hamid Dabashi, professor of cinema at Columbia University, who told me that art has long been an important, if sometimes inadvertent tool, for “muddying the political perception of a country that has been reduced to one thing in the media.

“Iranian cinema was one of the reasons [the US] didn’t invade Iran in 2001,” he believes.

To be sure, there are other reasons, including Iran’s military and its difficult terrain. At the time of 9-11, Iran also had a stable, open president in Khatami. But what goes on in the minds of Americans when they are listening to the news about a place we’ve just invaded or with whom we’re trying to negotiate peace? Nancy believes her exhibits are most effective then – partly because they are apparently so remote from politics.

“I chose artists who show their ancient culture in their work,” she told me, pausing, delicately choosing her words. “So that I could introduce the soul of the country to Americans”.

In this way, ‘soul’ includes a group of people’s values and their motivations in making decisions. Going far back in history helps Nancy get to this thing, which is why she so concerned with Iranian identity. If she can reveal this to Americans in a language they can understand – art - then she believes they’ll be more likely to understand Iranians when it comes to politics.

This year three Iranian artists – Shirin Neshat, Monir Farmanfarmaian and Parviz Tanavoli – had major retrospectives in the United States, at the Hirshhorn, Guggenheim and Wellesley College, respectively. Maryam Eisler, an Iranian collector and arts sponsor who was a major force behind two of them, told me how hard the exhibitions were to put on, even though Iranian artists have been doing similar shows for years in Europe. It’s impossible to pinpoint how or why this was finally feasible in 2015. One reason may, however, be that Nancy worked so hard to break the seal in 2001 when she presented the first ever modern Iranian art show in the United States.

Nancy follows a line of intellectuals beginning with America’s forefathers and, roughly, ending with the late William Fulbright, a senator from Arkansas who is best known for the fellowship program bearing his name. When in the 18th century the US was raising money for its revolutionary war against Britain, it turned to France for support. But France was not an easy country to ask things from – it had a culture full of strong, impenetrable values and was difficult to approach.

To handle this, America sent its most educated, most famous son, Benjamin Franklin. According to Professor Stanley Katz from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public Policy at Princeton, Franklin represented a school of thought stemming from the Enlightenment that “highly rational and well educated people in the world – but really, that meant the western world – were part of the same universe”.

In the 20th century, this morphed into a kind of “liberal internationalism,” Katz said, based on “exchange, travel and openness”. If this had come to fruition, Nancy’s exhibits would be par for the course. “But in America in the 20th century, that was always up against a kind of ‘island of America’ that isn’t just isolationism but includes it” and the view that “what really counts is what happens here”. After the second world war, this way of thinking was predominant. The potentially vast network of cultural exchange intellectuals was relegated to Fulbright’s educational programme, which is a highly competitive international educational exchange program founded in 1946. “In many ways, Fulbright was the last of his kind,” Katz said.

The ‘island of America’ mentality fed into conservatism in politics, Katz said, “most profoundly during the Reagan administration”. Once that happened, cultural exchange died for once and for all. While Obama is a liberal president, he rules in a time after cultural exchange. He can’t approach the kind of diplomacy that Nancy practised throughout her career, and when Nancy retired in 2008, the department shrank, foregoing corporate sponsors and depending on government funds for its programs.

“Obama’s only real foreign policy vision is an economic policy, but that’s a different kind of liberalism,” said Katz. Its concern is free trade, not cultural and social values. Cultural exchange has left the room. People like Nancy are on their own.

And never more so than when governments are at loggerheads. In 2007, Nancy was gearing up for a big China exhibition at Meridian but felt it was important to put on another Iran show. Yet President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad has been in power for two years, and much of President Khatami’s work to promote cultural understanding had been undone. Sami Azar had left the Museum for Contemporary Art before he was forced out, and the museum had lost trust among many artists.

“We had less money and fewer artists, but we wanted to make sure we got it in”. Nancy pulled together 34 artists for a second exhibition, four years after the first one.

Condoleezza Rice, the secretary of state, decided to show up for the opening at Meridian. “Once the media found out she was going to be there, reporters from the New York Times, from all over, came, and we got serious attention,” Nancy told me. “She wanted to show her support for the Iranian people”.

But what Secretary Rice didn’t understand was that cultural diplomacy is a long-range game to be practised over many years, regardless of politics. If you engage sporadically, or for politics alone, you are more likely just to disturb the waters than to make political headway. Much to Nancy’s chagrin, Secretary Rice’s stunt put some of her artists in harm’s way, and all were questioned when they returned to Iran.

Politics and art “don’t belong together”, said Nancy. But how is this reconciled with the obvious endgame of cultural diplomacy: mutually beneficial political relations?

“Well, one can support the other,” Nancy says, “but that can’t be the point”.

I asked Nancy whether she put on the 2007 exhibition hoping for some impact on negotiations over Iran’s nuclear programme. “Oh, no,” she said. “That wasn’t even on the table then”.

For Nancy, cultural diplomats must believe in the means rather than just the ends. She explained this to me with a story from her second trip to Iran, in December 1999. Her knowledge of the country was becoming more nuanced and would become more so on that night. Snow covered the high mountains north of Tehran. Christmas trees were displayed in small shopping centres throughout the city, all lit up.

At a large apartment in the south of the city, 20 or so people gathered around a table as Nancy and her Iranian co-workers celebrated her birthday. As is common, Hafez poetry began the night: a guitar was played and people sang along.

Someone leaned over and shared a piece of wisdom with Nancy: “We’re patient. We don’t want another revolution. We’re patient. We’ll wait”.

Nancy believes this line reveals a deep truth about the Iranian people: politics comes and goes, but the culture is resilient. It has endured conquerors and war for thousands of years and remains intact. Iranians can be patient with their government because it’s just one in a long line.

“We don’t understand things like that in the US,” she said. “We want change right now”.

This article is part of a multimedia project by ReframeIran published in partnership with The Tehran Bureau. Contact us @tehranbureau. The reporter can be reached @aglorios

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion