The 1970s and 1980s were a tumultuous time that tested the BBC severely. The 70s were characterised first by an apprehension of national decline and inertia, and then a panicked disorder. Yet by the mid-80s Britain was being remade at a furious pace on a new model, as an ebullient, get-rich-quick culture emerged. The Conservative government attacked, and yet in the last instance also protected, the Corporation.

The BBC had for decades helped to define Britain, yet by the late 80s, the Corporation was all too often the story, vulnerable to new commercial and political models, its capacity to exercise political balance tested by three Conservative election victories. Old sentimental certainties fell. Traditional restraints on the power of the British government appeared no longer to work.

Because state papers, previously closed, have now become available, it is possible to see the BBC in this era in a clearer light – its triumphs, its mistakes, the political assaults made on it and how it survived them. The Corporation inevitably got things wrong. It did not always question its own ideas or the conventions of the moment enough. It became defensive and arrogant. But when it blundered, the British people could demand that it try harder – which was part of its glory, because it was “ours”.

Broadcasting forged powerful collective experiences. Vast audiences gathered together every evening to watch the news. More than 20 million tuned in for critical episodes of EastEnders. This capacity to mobilise attention, allied with the BBC’s values of independence and quality, was eyed warily by politicians and commercial rivals. It is no wonder that its impartiality was bitterly disputed.

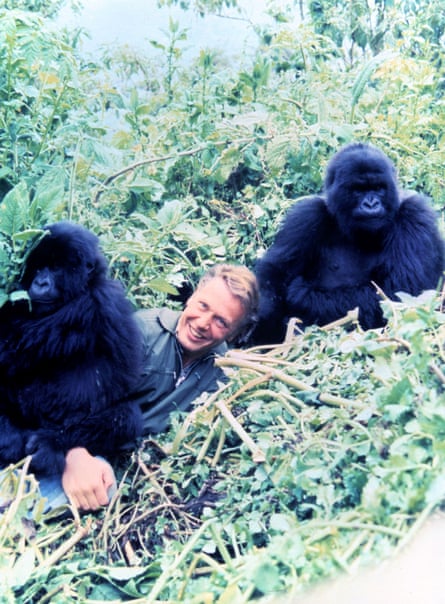

Audiences still had to choose to spend their time with the BBC. So the Corporation had to win and woo. When parts of it were out of step with the national mood, other parts were able to express that mood in surprising and successful ways. The original proposition for David Attenborough’s Life on Earth, first broadcast in 1979, was simple: that TV could be used to make a coherent intellectual argument over the 13 hours of a series. Where previous wildlife programmes had been content to show interesting animals or places, Life on Earth was Attenborough’s essay on Darwin. He thought that providing a way of “seeing” Darwin’s ideas in action would create a leap in public understanding.

The BBC represented the nation, and attention to the audience’s pleasures – through Gardeners’ World and Question Time; Blue Peter and Woman’s Hour; Dad’s Army, Radio 1, Just a Minute and the Proms – gave it unrivalled access to a cross-section of British life.

In the World Service the BBC was outward-facing. It was a precious gift to international intelligence, keenly followed by people hungry for truth but trapped in oppressive states during the cold war. After the fall of communism, it was greeted all over the former Eastern bloc with the same gratitude it met across occupied Europe at the end of the second world war. The World Service served British self-interest, but not by crassly championing government policy. Spending cuts had to be managed, and an absurd Labour plan in 1979 to reduce it to an anti-communist propaganda rump had to be fought off.

❦

The BBC continually reviewed the borders of political power. Politicians had previously pressured the Corporation, of course, but in the 70s and 80s, for the first time since it was founded, its very existence was put in question. Confrontation steadily escalated. Behind the backs of the British public, both Labour and Conservative governments considered a radical move. Labour planned to abolish the licence fee by bringing the BBC within general government expenditure. This was so controversial that relevant papers were marked “Secret” and their circulation restricted. The plans were backed by a coalition within cabinet which included, on the left, Tony Benn, who thought the BBC’s governors “undemocratic” and the licence fee an unfair poll tax on the poor, and on the right the prime minister, James Callaghan. (They agreed on little else except that they should “do” something about the BBC.)

This would have made the BBC a “state” broadcaster, competing head-on with health, education and defence for funds. Labour came in practice, if not in name, very close to doing this, when it gave the BBC three inadequate licence-fee settlements, resulting in straitened income budgets, eked out year by painful year. “Tethering” the BBC to the government in this way was driven by a desperate attempt to grapple with inflation, though there was an element of political exasperation with the BBC as well.

The challenge from the new Conservative administration, elected marginally in 1979 and triumphantly in 1983, was more fundamental. For the first time, the legitimacy of BBC values as well as their practice was directly contested. The government in the short term calmed licence-fee negotiations by taking the “permanent revolution” out of them. But it began to articulate a series of arguments: that the licence fee was a state handout inimical to free expression; that funding by advertising and greater “choice” between channels would be more democratic; that impartial news was a deception and “responsible national interest” a better value; that to articulate opposing views was biased and sometimes treacherous; that the BBC was part of an establishment that needed to be re-engineered. And so on. The BBC’s spending was seen as profligate, its plays political, its standards of taste and decency out of touch with the public. This was a strong, coherent attack on the Corporation’s founding principles, and as part of it, the BBC was forced to accommodate governors who were actively hostile, not merely critical.

❦

At the centre of this confrontation with the BBC was the formidable Mrs Thatcher. Papers in the BBC archives dating from the late 50s show her bouncing on to the BBC stage as a new MP. She was recognised straight away by the Corporation as one to watch. (As Bernard Ingham, her devoted press secretary, later said in a myth-making but accurate aside: she needed “lead weights not rocket boosters”.) The BBC never managed to steer itself into a more comfortable relationship with her; it became her “enemy”. At numerous levels within the Corporation they discussed what to do for her, with her, how to check her capacity to wipe the floor with interrogators, how to ration her appearances on Jimmy Savile’s shows. (The only discussion of Savile in the records of the BBC board of governors is a lively little debate about whether the appearances of Thatcher on his programmes – Jim’ll Fix It and his shows on Radio 1 and 2 – should be limited because she should have to face “hard” questions as well.) Thatcher bombarded the Corporation; in a sense, she wanted it to be “hers”. And remarkably, although she was usually observant of proprieties, she did not hesitate to seek approval from Rupert Murdoch for her suggestion for a new BBC chairman. No one back then seemed to find it odd.

While the BBC and the government slugged it out in public, they also cooperated in private and in the public interest over bigger issues: planning for the threat of nuclear Armageddon or the collapse of civil order. Because of this, BBC staff were vetted. The decision by the BBC, until Alasdair Milne became director-general in 1982, not merely to accept but to argue for greater vetting of its staff, was partly protective: when the Corporation was being routinely accused of infiltration by opponents of the state – of being full of pinkoes and traitors – the use of official clearance proved it was not. Even so, the offices of the DG and the chairman were regularly swept for bugs throughout this period, revealing a dark anxiety about surveillance and mutual suspicion between the BBC and the government.

❦

The conflicts in Northern Ireland and the Falklands presented a different set of problems. In Northern Ireland, as ministers flailed about, attempting to impose order amid intercommunity violence, catastrophic mistakes were made. The BBC, the messenger carrying unpalatable stories, was often blamed. The lord chief justice at one point said that “the BBC would have given Satan and Jesus Christ equal time”. Keith Kyle, reporting on Bloody Sunday, used the word “massacre”, and as a result the army, the Northern Irish government, the NI office in London, the PM’s office, all went ballistic. The head of news replied steadily that “shootings”, “killings” and “incident” were not accurate – massacre was the only word he would allow.

The BBC was seen as especially treacherous by the Protestant community, and the fine Corporation building on Ormeau Avenue, Belfast, was repeatedly targeted. (A BBC memo in 1982 cheerily reported: “Only 65 windows gone this time!”) The Labour government, in secret, considered an extraordinary intervention in the ownership of commercial Thames TV to make it more compliant, while civil servants discussed how to manage individual BBC journalists. Perhaps even more lethally, in the margins of the Privy Council, out of sight of the broadcasters, Conservative and Labour ministers formed an informal coalition against the BBC, agreeing a strategy to intervene to get the kind of reporting they wanted, to be followed by appeals to the BBC governors, and if that did not work to “reform” the governors.

Rows about programmes blew up from nowhere – not least because experience in Northern Ireland was becoming so removed from that in the metropolis. But the evidence shows too that civil servants mostly fought the imposition of a broadcasting ban for over a decade, and that William Whitelaw, the home secretary, was talking to the IRA earlier than was previously known. What did not falter was the BBC’s determination that its news about Northern Ireland should be fast, accurate and responsible.

The Falklands war was fast, furious and risky in a different way. Mrs Thatcher’s political future depended on it and something sulphurous in the relationship between the Corporation and the government emerged from it. The military campaign was touch and go, and this led to censorship, when the BBC could instead have been a trustworthy confidant.

It nevertheless won the reporting war on the frontline with model journalism. The world went on listening to the World Service’s reports on the conflict – because it remained the best, most accurate source of information. On the other hand, the Corporation lost the home front; Milne, who regarded the war as an imperial hangover, was badly damaged by a confrontation with braying MPs. Presenter Peter Snow was accused of treachery for calling the troops “the British” (rather than “our troops”) on a brilliant new invention called Newsnight, leading to unprecedented attacks from a nationalist popular press – though it turned out he was following established government policy in doing so. The press accused the BBC of reporting information that led to the death of a soldier; the briefing, however, came from a government minister.

❦

There were uncomfortable aspects of the BBC that didn’t appear on the charge sheet drawn up by politicians at the time. A new senior BBC administrator, appointed to a job in 1982 with strategic reach across the organisation, surveyed with satisfaction their new elegant wood-panelled office in Broadcasting House. A large 1930s safe with a wheeled handle seemed to signify the importance of the new post. What might it contain? The BBC Charter? The Armageddon File, with instructions for what the BBC was to do in the aftermath of a nuclear attack? A security expert arrived with the combination. After clearing staff out from the side office, he swung the safe open. It was empty except for a slim manila envelope. This contained a completed expense form, for what appeared to be the use of a prostitute on the Orient Express by George Howard, the grandee owner of Castle Howard (televised in Brideshead Revisited in 1981), chair of the Country Landowners Association, and BBC chair of governors from 1980 to 1983. The document had been left as a warning by the previous incumbent. But Howard was a man with a fine war record, a friend of the home secretary, and had been appointed by the Conservative government. To whom could the BBC turn?

By the 70s a new generation of women was thundering through the BBC, but encountering a world that seems quite alien now. They had tremendous working lives, and their history is a strong example of how disadvantaged voices have to struggle and how institutions have to be reinvented – they helped bring the contemporary world into being. The BBC had been a progressive employer and always knew its female audiences mattered. But the progress of women towards the top of the BBC is not a straightforward story of progress. Much later, when a group of women with successful careers in the Corporation met and compiled a list of men they had had “trouble” with – presenters, journalists, directors, administrators – gales of laughter greeted each name. One of them proposed they all wore T-shirts emblazoned: “We survived the groping years.” More perturbing was the sexual exploitation of other, younger, less articulate women in the audiences by BBC figures such as Savile.

❦

The Corporation was always characterised by anxiety. It did nothing casually. The worrying about values that resulted in great programmes had to go from the top (if it was working right) to the bottom. Evidence of this is everywhere in the archives. The creative processes and delicate wooing that led to Alec Guinness’s great performance as George Smiley in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1979) are displayed in a riveting set of papers. The all-important principles were considered with every broadcasting event, particularly during sensitive stories: decisions, for instance, over what to broadcast into Iran during the 1979 revolution.

Many “deep structures” functioned exceptionally well. Attenborough, for example, exemplified public-service BBC, producing great swaths of television in a distinguished career. Life on Earth could not have happened without decades of highly professional dedication in the BBC’s western region in Bristol, investment in science at the very heart of BBC programme-making, and the assembling of a team of passionate experts. The series emerged triumphantly out of rows and clashing principles, tactfully bound together by Attenborough as leader.

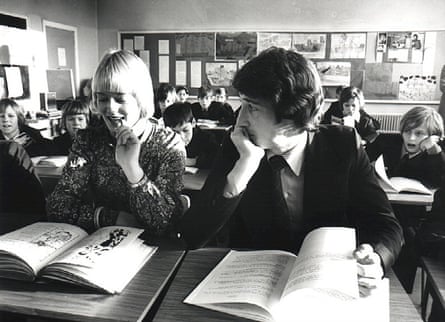

Meanwhile a programme such as the children’s drama Grange Hill, first broadcast in 1978, caused a riot of public and official complaint. It dealt with life in a gritty urban comprehensive school and had been deeply researched. The series tackled uncomfortable issues such as teenage sex, drugs, racism and bullying, and the “taste and decency” fundamentalists (who caused the BBC much political grief later in the 80s) immediately attacked it, so that it was demonised in the popular press for leading the nation’s youth astray. But “as the press launched into us and No 10 was complaining loudly to the DG”, said Anna Home, the director of children’s programming, “the Department of Health became very interested – after all we were tackling just the issues they were concerned with, but better than they could”. And Grange Hill was popular. The BBC did not do government campaigns. It did not accept direction about what issues it should take up or how to do them. It brought separate, careful intelligence to the reality of the nation’s condition.

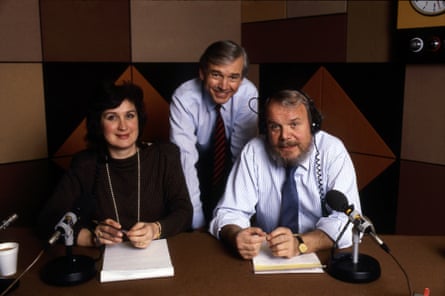

In difficult times, the BBC needed to provide everyday fun – the kind of delight derived from The Morecambe & Wise Show. Being popular was fundamental to the BBC – it had to serve everyone. It did so by inventing EastEnders in 1985, full of melodrama and matters of real public interest, but at the same time, it made programmes – Panorama, 24 Hours, Newsnight – that reinvented the news in ways that put the British public in charge of its own story. Through all of these, issues of balance, fairness and serving the public were encountered and assessed. BBC mandarins and the shock troops of programme makers tried (and sometimes failed) to find the lines that distinguished what the BBC as a public service broadcaster ought to do from the things it ought not to do.

❦

When Thatcher intervened in the constitutional conventions that had guarded the Corporation’s independence from government, Whitelaw cashed in his loyalty to the prime minister to protect the BBC. The Home Office (amid much gnashing of teeth, rows, occasional fury and plots) often came to the BBC’s aid. Home secretaries could be infuriated by the Corporation, but were often vigilant within government in protecting sacred BBC territory. The Corporation also formed and reflected attitudes towards another institution that marked British exceptionalism: the monarchy. Both institutions had an obligation to the entire nation and were providers of public spectacle. The Corporation’s royal files and records of interviews at Buckingham Palace offer a snapshot of a relationship that was vital but tested during the 80s.

BBC outside broadcasters understood how to put together a satisfying royal show, and they depended on a delicate collaboration with the Palace. Corporation papers show the monarchy, especially Prince Philip, supervising the construction of the royal image as broadcast on TV. At the heart of this relationship in these decades is the glittering royal frenzy that was the marriage of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer. The entire outside-broadcast team, seeing Diana weep at the wedding rehearsal, kept the secret, making sure the pictures did not reach the newsroom. The unit was the trustworthy guardian of a young woman’s mood. Yet later, as the royal marriage collapsed and royal fortunes wavered, the BBC often failed to apply all of its institutional intelligence to the gathering crisis.

❦

By 1987, faced by an apparently uncontrollable set of crises, everything the BBC did came under political attack. Great plays caused rows, not such good plays caused rows, the non-broadcasting of plays caused rows. There was a bleak atmosphere of panic and crisis, fantasies of plots and real plots. The director-general, Milne, was forced to resign. Yet despite all the threats, the Corporation endured. It did so because it largely told audiences things they recognised to be true. It brought them programmes they loved and showed them an image of their lives that made them thoughtful, but also cheered them up. It respected and listened to them, and even in hard economic and political times made them feel proud of their realism. It explained the world and offered them the incomparable reporting of Charles Wheeler and his like.

George Orwell wrote: “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.” The BBC paid a high price for trying to put this demanding standard into practice. Yet it survived – because informing, educating and entertaining the public meant that it was held dear. Perhaps because the only institutions that people love are those that touch the imagination.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion