Ally or Adversary? Public Opinion of NATO in Post-Soviet Russia

[View PDF]

by Bret Schafer

ABSTRACT

According to the Pew Research Center, in 2015, only 12% of Russians held a favorable view of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).[1] The percentage of respondents who viewed NATO in strongly negative terms was even more striking: 50% had a “very unfavorable” view of the Alliance, a 36 percentage point increase compared to results from 2010.[2] While International Relations scholars continue to debate the causal connection between public opinion and foreign policy (Holsti 2004; Zimmerman 2002; Goldsmith 2012), the intensification of anti-NATO rhetoric that has emerged in Russian public discourse holds important and troubling implications for the future of NATO-Russia relations. Recognizing the gravity of those relations vis-à-vis global peace and security, this study aims to elucidate the causes and temporal connections between Russian attitudes towards NATO and the Alliance’s missions, policies, and public diplomacy initiatives. Through analysis of public opinion polls, this paper concludes that NATO’s popularity is largely determined by and linked to the popularity of its strongest member state: The United States. In addition, media analysis suggests that despite NATO’s public diplomacy efforts to “forge a constructive relationship with Russia,”[3] the Alliance is still almost universally portrayed by the Russian media as an adversarial and confrontational force. While these findings tend to support the theory that even sound public diplomacy cannot overcome unpopular policies, this paper also suggests that NATO’s current strategic communications strategy towards Russia has not only been ineffective but also largely counter-productive.

INTRODUCTION

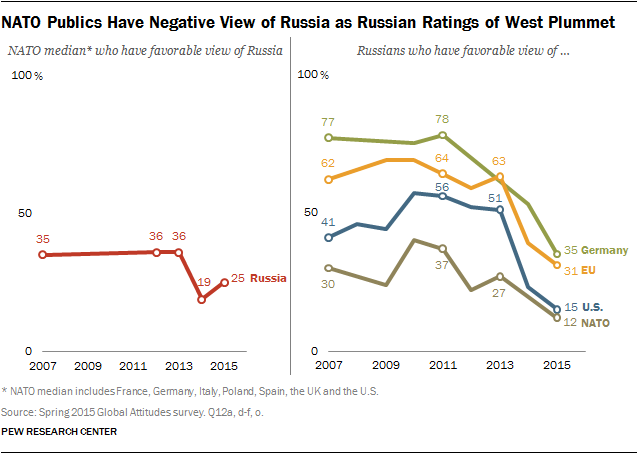

Since the Pew Research Center began polling Russian attitudes towards the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 2007, Russian views of NATO have been significantly less favorable than Russian views of the countries that contribute to the Alliance, including the United States.[4] On the one hand, it is hardly surprising that Russian opinions of NATO are less favorable than their opinions of the individual member states that compose NATO. As a military alliance, NATO lacks the soft power assets – culture, in particular – that can be employed to persuade or influence other countries through “attraction rather than coercion” (Nye 2008). Even though NATO is comprised of countries with significant soft power resources, those resources are generally attributed to the individual member states, not the Alliance. Without the currency and influence that comes with soft power, NATO’s image is therefore defined by less popular, hard power resources, namely its military clout. Indeed, if Russians were polled as to their opinions of any of the western powers’ armed forces – America’s in particular – their opinions would undoubtedly be less favorable than their opinions of the countries as a whole. Simply put, it is axiomatic that a foreign military power would be viewed less favorably than a country that can draw goodwill from its more benevolent and benign elements.

TABLE 1.1

At the same time, the fact that Russian attitudes towards NATO have consistently and, at times, substantially been less favorable than their views of their Cold War nemesis, the United States, suggests that NATO’s image problem may not be solely attributable to anti-hard power sentiments. While there has been significant literature devoted to the causes of Russia’s fractured relationship with NATO, this paper seeks to confront those potential causes systematically by studying Russian public opinion polls as well as the Russian media’s coverage of NATO. In so doing, it hopes to address several important questions:

- Are Russian opinions of NATO simply a vestige of Cold-War hostility; i.e., is the Alliance’s unpopularity among the Russian public so deep-rooted that it is unlikely to ever improve?

- Are Russian opinions of NATO independent of Russian opinions of the United States and the European Union; that is, are Russian views of NATO simply a reflection of their attitudes towards EU and U.S. foreign policy?

- Does the Russian media’s coverage of NATO reflect the sentiments of the Russian public?

- And, finally, have NATO’s public diplomacy endeavors had any positive impact on the opinions of Russians towards the Alliance?

Understanding the root causes of the Russian public’s negative attitude towards the Alliance is important for several reasons. Not least, it matters for Russian-NATO relations.

More than two decades after the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the collapse of communist regimes across Eastern Europe, the importance of Russia vis-à-vis NATO’s strategic security goals remains vitally important. From terrorism to issues as diverse as energy security and nuclear proliferation, there is not a single global security threat that is not profoundly affected by developments in Russia and the former USSR. Simply put, cooperation with Russia is essential if NATO is to mitigate those threats and achieve stability and security in Europe and the Middle East.

In addition, adverse Russian reactions to NATO policies can contribute, and likely have contributed, to regional instability. In the 1990s, Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service emphasized that NATO expansion into the Warsaw Pact would cause a “psychological storm” in Russia (Black 2000: 8). While NATO attempted to ameliorate Russian fears of its eastward expansion, its inability to successfully address Russian concerns have inflamed Russian paranoia over NATO’s geopolitical motives. The crises in Ukraine and Georgia are, at least partly, symptoms of that paranoia. In the case of Ukraine, the West’s overtures to Kiev (and vice versa) directly or indirectly contributed to Russia’s annexation of Crimea (Mearsheimer 2014). Therefore, understanding Russian public opinion is not simply a matter of popularity, it is a matter of global security.

RUSSIAN PUBLIC OPINION – CAN IT BE TRUSTED?

Before analyzing the causes of the Russian public’s negative views towards NATO, it is important to address concerns over the reliability of Russian polling data. Given Russia’s authoritarian history, the issue of whether or not public opinion polling accurately reflects the mood of the Russian public has been raised by several diplomats and journalists. According to Ben Judah, the author of Fragile Empire: How Russia Fell In and Out of Love with Vladimir Putin, Russian poll numbers cannot be trusted:

“An opinion poll can only be conducted in a democracy with a free press. In a country with no free press, where people are arrested for expressing their opinions, where the truth is hidden from them, where the media even online is almost all controlled by the government -- when a pollster phones people up and asks, 'Hello, do you approve of Vladimir Putin,' the answer is overwhelmingly yes” (Ahmed 2015).

The theory is that due to the legacy of KGB monitoring and the at times brutal repression of free speech, Russian respondents are cowed into parroting the official Kremlin-line. The data, however, does not support this claim. Daniel Treisman’s 2010 survey of Russian presidential approval ratings found that public opinion was, in fact, closely and rationally linked to perceptions of economic performance. In addition, his findings did not support the theory that Russians are somehow afraid to voice their opinions:

“Asked in 2004 whether there was more or less corruption and abuse of power in the highest state organs than a year before, 30 percent said more, 45 percent said the same amount, and only 13 percent said less. Respondents were not shy to give Yeltsin a 6 percent approval rating and Putin just 31 percent in 1999. Even as Russians swooned over Putin, his governments never won the approval of more than 46 percent, and large majorities opposed some of his policies, including—after the initial period—the military occupation of Chechnya” (Tresiman 2010: 4).

If Russians felt comfortable enough to criticize state corruption and their own presidents, it is unlikely that their views of the U.S. and NATO would somehow be swayed by a fear, rational or otherwise, that their opinions could land them a one-way ticket to Siberia. If we can therefore assume that the data is accurate, the results present a grave challenge for NATO’s public diplomacy practitioners.

HISTORICAL INFLUENCES ON PUBLIC OPINION

Given the historical animosity between NATO and the USSR, it was perhaps inevitable that the Russian public would continue to harbor mistrust of the Alliance after the collapse of the Soviet Union. For more than 50 years, NATO’s primary objective was to contain the threat of the Warsaw Pact’s expansion into Western Europe, and vice versa. With the dissolution of the Pact, the threat of NATO’s encroachment into Russia’s ”near abroad” became a more, not less, realistic threat. Therefore, NATO’s eastward expansion into former Warsaw Pact countries has undoubtedly been one of the most important developments in post-Cold War NATO-Russian relations (Zimmerman 2002).

At the heart of the debate over NATO’s ”Open Door” policy is the contestation over an alleged promise made to Moscow at the end of the Cold War. Russian officials and diplomats regularly assert that Washington and Brussels entered a pact with the Soviet Union to not expand the alliance eastward in exchange for Moscow’s tacit approval of German reunification (Sarotte 2014). While NATO explicitly rejects this claim (NATO-Russia: The Facts 2015), declassified documents from the West German foreign ministry clearly suggest that the Soviet response to the possibility of NATO’s expansion was not only a matter of discussion but also a serious geopolitical concern. West German foreign minister, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, suggested to his British counterpart, Douglas Hurd, that NATO make a public statement to express that “NATO does not intend to expand its territory to the East. Such a statement must refer not just to [East Germany], but rather be of a general nature,” he added. “For example, the Soviet Union needs the security of knowing that Hungary, if it has a change of government, will not become part of the Western Alliance” (Sarotte 2014).

Obviously, the West’s position changed. And whether or not Washington or Brussels made any formal assurances to the Kremlin, the narrative of duplicity has had a profound impact on the Russian media’s coverage of NATO’s eastward drift (Felgenhauer 1997). But did that negative coverage poison the well of Russian public opinion towards NATO?

Opinion polls from the 1990s seem to suggest that while NATO’s expansion was a salient issue for Russian elites from the very early stages of the post-Soviet transition, it only became a major policy issue for the Russian public in the late nineties after NATO’s involvement in the Balkans (Zimmerman 2002; Felgenhauer 1997). In 1995, a poll assessing Russian elite’s assessment of threats to national security indicated that NATO’s expansion was viewed as the most significant danger, more than “the growth of U.S. military power” or an “inability to resolve domestic conflicts” (Zimmerman 2002: 190). The Russian public, however, was far less concerned with NATO’s expansion. Table 2.1 indicates that the mass public viewed NATO’s expansion as a far less ominous threat than a multitude of domestic and regional issues.

TABLE 2.1

Russian Mass Public Assessment of Threats to Russian Security (1 = absence of danger; 5 = greatest danger)

|

|

1995 |

1999 |

|

“Uncontrolled growth in global population” |

2.28 |

---- |

|

“Increase in the gap between rich and poor countries” |

3.14 |

3.49 |

|

“Spread of NATO to Eastern Europe” |

3.48 |

---- |

|

“Growth of U.S. military power” |

3.74 |

4.01 |

|

“NATO intervention in internal affairs of European countries” |

----- |

4.03 |

|

“Border conflicts with the CIS” |

3.91 |

3.90 |

|

“Involvement in conflicts that don’t concern Russia” |

3.96 |

4.15 |

|

“Non-CIS conflicts” |

3.99 |

4.11 |

|

“Having key economic sectors in foreign hands” |

4.02 |

---- |

|

“Inability to resolve domestic conflicts” |

4.14 |

4.20 |

Source: Demoscope as reported in Zimmerman (2002)

In addition, the public reaction in Russia to the Alliance’s first eastward expansion (into Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic) was largely divided or, more precisely, indifferent. In 1997, 43% of respondents in Russia replied that they were not aware of NATO’s plans to expand to the East.[5] Of those who indicated that they were aware of NATO’s plans to expand, roughly half incorrectly identified the three Baltic countries (Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia) as the countries that were slated to join the Alliance, while fewer than a quarter correctly identified Hungary and the Czech Republic (42% correctly identified Poland).[6] These findings certainly suggest that the issue of NATO’s eastward expansion was of little importance before NATO adopted a more aggressive approach towards Serbia.

Writing in the Moscow Times at the end of the decade, Pavel Felgenhauer wrote of NATO’s then-Secretary General Javier Solana’s failed “charm offensive” to temper Russian concerns over eastward expansion:

“All major mainstream political forces in Russia are as adamantly against NATO today as they ever were. What is changing, however, is public opinion. Previous polls showed the majority of ordinary Russians indifferent to the NATO issue. But the results of the most recent poll carried out by the Russian Center for Public Opinion presents a different picture: 50 percent of those polled are against any former Soviet republic becoming a NATO member, with only 13 percent in favor, and 41 percent are against any East European state becoming a NATO member, with 15 percent in favor. Only 8 percent of those polled believe Russia itself should become a NATO member” (Felgenhauer 1997).

The souring of Russian public opinion over NATO’s expansion and expanded role also overshadowed the many positive steps taken by Russia and NATO in the 1990s to improve interoperability and cooperation. Russian-NATO attempts to forge closer bonds through joint peacekeeping missions in Bosnia (Operation Joint Endeavor and Operation Joint Guard/Operation Joint Forge); the 1997 Founding Act, which established a permanent Joint Council comprised of NATO countries and Russia; and the Partnership for Peace, which was initiated in 1991 to foster better relations between NATO and former Warsaw Pact members (Ponsard 2007; Saunders 2000) all failed to register with the Russian public compared to the issues of NATO’s expansion and involvement in Kosovo.

These findings suggest two critical points. First, the current unfavorable views of the Russian public towards NATO are less a vestige of Cold War thinking than a reaction to NATO’s post-Soviet policies and eastward expansion. And second, unpopular policies can overshadow public diplomacy efforts to improve engagement and cooperation. While these findings are important in understanding the general unpopularity of NATO, they do not necessarily explain the year-by-year fluctuation in NATO’s popularity with the Russian public. Because if fears of encirclement are the driving factor for negative opinions of NATO, one would assume that any period of expansion would have a detrimental effect on public opinion. But this has not necessarily been the case.

As indicated in Figure 1.1, NATO’s favorability among the Russian public skyrocketed between 2009-2010 (from 24% to 40%) at a time when the Alliance expanded to include Croatia and Albania. During that same time period, favorable opinions of America also dramatically improved (from 44% to 57%). Therefore, the results beg the question: Is NATO simply viewed as an extension of American or EU foreign policy; i.e., are Russian opinions of NATO merely a reflection of their opinions of the two “superpowers” that compose NATO?

CORRELATION BETWEEN OPINIONS OF NATO, THE EU, AND THE UNITED STATES

In order to test this theory, public opinion polls from the Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Survey from 2007-2015 were analyzed in order to track the strength of the relationship between Russian opinions of the EU and NATO, and the strength of the relationship between Russian opinions of the United States and NATO. Given the finding that Russian opinions of NATO have always been lower than opinions of the individual member states (likely due to soft vs. hard power considerations), this analysis was designed to test the correlation between the year-by-year change in the percentage of Russians who had favorable or very unfavorable views towards the EU, U.S., and NATO, rather than the correlation between the raw percentage of respondents with favorable or unfavorable views in a specific year. It was my belief that this would provide a more accurate reflection of the correlation between Russian public opinions of NATO and their opinions of the U.S. and EU.

Pew’s polling data from 2007-2015 was selected as the source of analysis because it represented the most consistent polling data, both in terms of the number of years measured and the framing of the questions respondents were asked. It would have been extremely beneficial to measure Russian public opinion of NATO going back to the early Yeltsin years; unfortunately, that data was not available. While questions about NATO were occasionally posed to Russian respondents prior to 2007, those questions often referred to specific NATO policies (e.g. expansion into Georgia or the Baltics) rather than overall opinions of the Alliance. For example, prior to 2007 (when Pew included the NATO question in its yearly surveys), questions about NATO were typically posed by Pew (as well as the Levada Center and VCIOM, two of Russia’s most reliable public research institutions) during flashpoints; e.g. before rounds of NATO expansion or during increased periods of tension between Russia and the West. As a result, that data would likely skew the results by including more negative responses than would be expected if questions were posed in a more neutral geopolitical environment. Therefore, despite the limitations of such a limited sample size, it was determined that measuring the responses in Pew’s 2007-2015 surveys would yield the most accurate results. It should also be noted that due to the fact that Pew did not survey Russian opinions of NATO in 2008 and 2014, the “year-by-year” changes in favorable and very unfavorable attitudes in 2009 and 2015 were measured against data from 2007 and 2013 respectively. This allowed the sample units to remain consistent between all variables tested.

In order to test the strength of the relationship between changes in Russian opinions of the EU and NATO and changes in Russian opinions of the United States and NATO, a regression analysis was performed using the following formula:

r = Σ (xy) / sqrt [ ( Σ x2 ) * ( Σ y2 ) ]

In the above formula, (r) represents the correlation coefficient. The absolute value of a correlation coefficient describes the direction and strength of the relationship between two variables, in this case the relationship between favorable and very unfavorable opinions of the EU and NATO, and the United States and NATO. An absolute value of 0 would indicate the weakest connection between the variables, while a correlation coefficient of 1 or -1 would indicate the strongest connection between the variables. A negative correlation would represent an inverse relationship between the two variables; i.e., if public opinion of one variable (the EU or U.S.) increased or decreased, public opinion of the other variable (NATO) would tend to move in the opposite direction. A positive correlation would mean that as public opinion of the EU or the U.S. increased or decreased, public opinion of NATO would tend to move in the same direction.[7] The closer the absolute value of (r) is to 1 or -1, the stronger the linear association between the two variables; however, strength of a relationship does not necessarily mean that it is statistically significant. In order to determine statistical significance, one must also factor in the sample size. In this case, with the percentage change of favorable and very unfavorable responses measured over six different time periods between 2007-2015, an (r) value of greater than .73 would be needed in order to be considered statistically significant.[8]

As indicated in Table 3.1, the percentage of Russians with favorable views of the U.S. and NATO decreased in the same time period four times, increased one time (2009-2010), and moved in opposite directions one time (favorable views of the U.S. increased between 2007-2009, while favorable views of NATO decreased during the same time period). As might be expected, the change in the percentage of Russians with favorable opinions of NATO proved to be highly correlated with the change in the percentage of Russians with favorable opinions of the United States (see Table 3.2). At r = .803379, the findings also proved to be statistically significant. In layman’s terms, the results indicate that when favorable opinions of the United States increase, favorable opinions of NATO also tend to increase.

TABLE 3.1

Percentage of Russians with favorable views of the United States, NATO, and EU

Pew Research Center

|

Year |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

U.S. |

41 |

46 |

44 |

57 |

56 |

52 |

51 |

23 |

15 |

|

Percentage point change of favorable views towards U.S. from previous year* |

---- |

---- |

3 |

13 |

-1 |

-4 |

-1 |

---- |

-36 |

|

NATO |

30 |

---- |

24 |

40 |

37 |

31 |

27 |

---- |

12 |

|

Percentage point change of favorable views towards NATO from previous year* |

---- |

---- |

-6 |

16 |

-3 |

-6 |

-4 |

---- |

-15 |

|

European Union |

62 |

---- |

69 |

69 |

64 |

59 |

63 |

39 |

31 |

|

Percentage point change of favorable views towards the EU from previous year* |

---- |

---- |

7 |

0 |

-5 |

-5 |

4 |

---- |

-32 |

*Due to gaps in polling data of Russian views towards NATO, percent change for Russian views towards NATO, the EU, and the United States in 2009 and 2015 were measured against poll results from 2007 and 2013 respectively.

Question 1: Please tell me if you have a very favorable, somewhat favorable, somewhat unfavorable, or very unfavorable opinion of...the United States.[9]

Question 2: Please tell me if you have a very favorable, somewhat favorable, somewhat unfavorable, or very unfavorable opinion of...NATO, that is, North Atlantic Treaty Organization.[10]

Question 3: Please tell me if you have a very favorable, somewhat favorable, somewhat unfavorable, or very unfavorable opinion of...the European Union.[11]

FIGURE 3.2

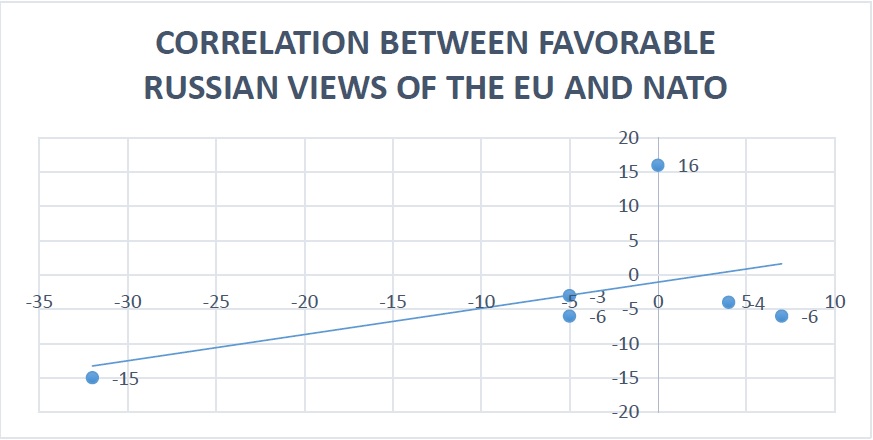

Correlation between favorable Russian views of the U.S. and NATO r = 0.803379

In comparison, the percentage of Russians with favorable views of the EU and NATO decreased in the same time period three times, and moved in opposite directions two times (between 2009-2010 there was no change in the percentage of respondents with favorable views of the EU, while favorable views of NATO increased 16 percentage points). While there was a moderate correlation (r = 0.522218) between the percentage of Russians with favorable views of EU and the percentage of Russians with favorable views of NATO, the findings were not statistically significant (see Figure 3.3), and certainly less highly correlated than the relationship between favorable opinions of the U.S. and NATO.

FIGURE 3.3

Correlation between favorable Russian views of the EU and NATO r = 0.522218

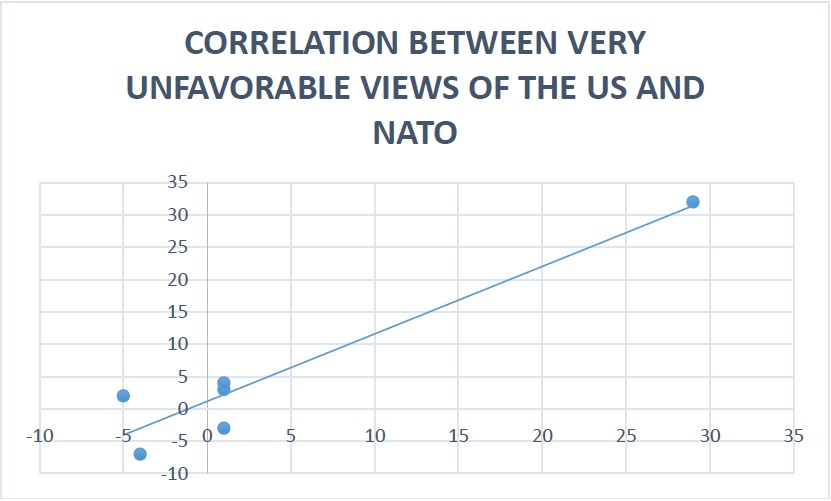

In addition, I also tested the relationship between very unfavorable opinions. As indicated in Table 3.4, the percentage of Russians with very unfavorable views of the U.S. and the percentage of Russians with very unfavorable views of NATO increased in the same time period three times, and moved in the opposite direction three times. That said, in the years where views of one improved while views of the other declined, the difference was quite small. For example, between 2012-2013 those with very unfavorable views of the United States increased by only 1%, while those with very unfavorable views of NATO decreased by only 3%. As a result, the relationship between very unfavorable views of the United States and very unfavorable views of NATO (see Figure 3.5) was even stronger (r = .954887) than the correlation between favorable views of the United States and favorable views of NATO.

TABLE 3.4

Percentage of Russians with “very unfavorable” views of the United States, NATO, and EU

Pew Research

|

Year |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

U.S. |

16 |

20 |

11 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

34 |

39 |

|

Percentage point change of very unfavorable views towards US from previous year* |

---- |

---- |

-5 |

-4 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

---- |

29 |

|

NATO |

20 |

---- |

22 |

14 |

17 |

21 |

18 |

---- |

50 |

|

Percentage point change of very unfavorable views towards NATO from previous year* |

---- |

---- |

2 |

-7 |

3 |

4 |

-3 |

---- |

32 |

|

EU |

3 |

---- |

4 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

6 |

17 |

20 |

|

Percentage point change of very unfavorable views towards EU from previous year* |

---- |

---- |

1 |

-1 |

2 |

-1 |

2 |

---- |

14 |

*Due to gaps in polling data of Russian views towards NATO, percentage point change for Russian views towards NATO, the EU, and the United States in 2009 and 2015 were measured against poll results from 2007 and 2013 respectively.

Question 1: Please tell me if you have a very favorable, somewhat favorable, somewhat unfavorable, or very unfavorable opinion of...the United States.[12]

Question 2: Please tell me if you have a very favorable, somewhat favorable, somewhat unfavorable, or very unfavorable opinion of...NATO, that is, North Atlantic Treaty Organization.[13]

Question 3: Please tell me if you have a very favorable, somewhat favorable, somewhat unfavorable, or very unfavorable opinion of...the European Union.[14]

FIGURE 3.5

Correlation between very unfavorable Russian views of the US and NATO r = 954887

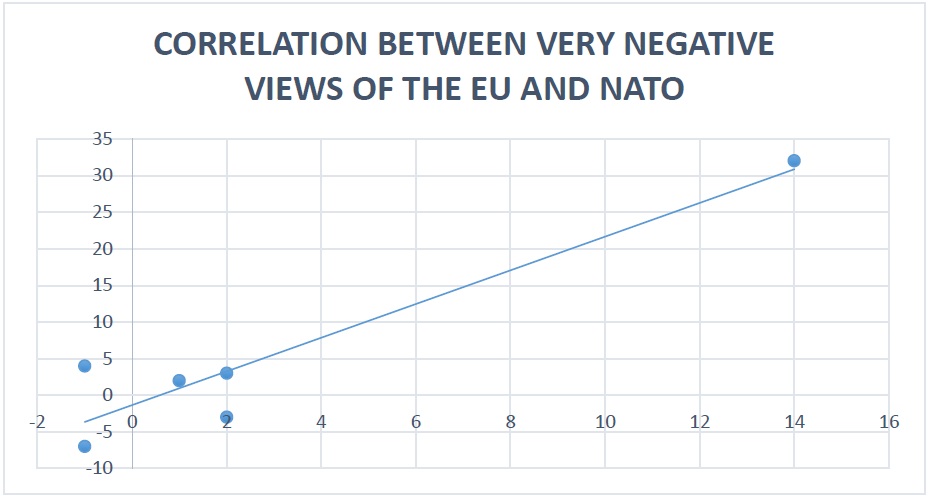

The relationship between the EU and NATO was also analyzed in order to determine if there was a correlation between very unfavorable opinions. In this case, the percentage of Russians with very unfavorable views of the EU and the percentage of Russians with very unfavorable views of NATO increased or decreased in the same time period four times, and moved in opposite directions two times. As shown in Figure 3.6, the results again indicate a very high correlation (r = .939654) between very unfavorable views of the EU and very unfavorable views of NATO (although the results are slightly less significant than the US/NATO results).

The relationship between the EU and NATO was also analyzed in order to determine if there was a correlation between very unfavorable opinions. In this case, the percentage of Russians with very unfavorable views of the EU and the percentage of Russians with very unfavorable views of NATO increased or decreased in the same time period four times, and moved in opposite directions two times. As shown in Figure 3.6, the results again indicate a very high correlation (r = .939654) between very unfavorable views of the EU and very unfavorable views of NATO (although the results are slightly less significant than the US/NATO results).

FIGURE 3.6

Correlation between very unfavorable Russian views of the EU and NATO r = 939654

These results suggest that in both cases very unfavorable views are more highly correlated than favorable views. The results also suggest that, overall, Russian views of the U.S. and NATO are more closely related than Russian views of the EU and NATO. While the analysis suggests a strong, general linkage between views of the U.S. and NATO, it is difficult to determine from quantitative data why the linkage exists, or the specific factors that drove positive and negative views of NATO and its two biggest contributors. While that analysis always calls for a degree of speculation, it is useful to look at the critical geopolitical signposts that could explain the variances and fluctuations in the data.

BEHIND THE NUMBERS

In all cases, the greatest decline in the percentage of respondents with favorable views, as well as the greatest increase in the percentage of respondents with very unfavorable views, occurred between 2013-2015, which clearly coincides with the crisis in Ukraine. The toxic cocktail of Western-backed economic sanctions, an increase in negative media rhetoric, a spike in ethnic bloodshed in Ukraine’s Russian-speaking east, and a “rallying around the flag” effect due to the annexation of Crime led to plummeting opinions of all western powers. Those findings, coupled with the astronomical and, some would argue, irrational approval ratings of Vladimir Putin[15] (especially given the state of the Russian economy) (Treisman 2010) suggest that current negative attitudes towards NATO reflect a more general anti-Western sentiment than a more specific, anti-Alliance or anti-American sentiment. This “rallying around the flag” effect makes any analysis of current trends potentially specious due to the fact that attitudes may be driven more by patriotic passions than well-reasoned logic.

In terms of identifying the effects of specific geopolitical events shaping Russian views of NATO, two time periods periods require deeper analysis: 2007-2009 and 2009-2010. Between 2007-2009, Russians with favorable views of NATO dipped from 30% to 24%, and those with “very unfavorable” views of the alliance increased from 20% to 22%. While the drop in NATO’s favorability was clearly less significant than between 2013-2015, the declining popularity of NATO came at a time when Russian views towards the West were generally positive and improving (see Table 3.1). During this same period, Russian opinions of both the United States and the European Union improved marginally (by 3% and 7% respectively). This finding provokes an interesting question: what caused opinions of NATO to worsen while opinions of its two key members improved?

First, it is necessary to identify the key geopolitical events that could have influenced Russian opinions (see Table 4.1). During 2007-2008, the most notable event vis-à-vis Russia’s relations with the West was the 2008 war with Georgia. While the war was sparked by ethnic tensions within Georgia, geopolitics and the question of NATO expansion played a significant role. When President Putin and American President George W. Bush met at the NATO summit in Bucharest in 2008, Putin allegedly warned Bush that any attempt to expand the Alliance into Ukraine or Georgia could prompt Russia to encourage the Russian-speaking territories in those countries to break away (Kramer 2008). Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov echoed that sentiment when he remarked, “Russia will do everything it can to prevent the admission of Ukraine and Georgia into NATO” (Kramer 2008: 9).

When polled in 2008, the Russian public seemed to reflect their leaders’ misgivings about the Alliance’s plans to expand. In 2008, 68% of surveyed Russians responded that Ukraine joining NATO would constitute a threat to the security of Russia. Likewise, 74% felt that Georgia’s inclusion in NATO would threaten Russian security (Levada Center 2008). This contrasts sharply with polling in the early 1990s that showed a general ambivalence towards expansion. Clearly, the prospect of NATO moving into Russia’s ”near abroad” either constituted a greater threat than earlier rounds of expansion or, possibly, the cumulative effects of NATO’s actions and twenty years of negative media coverage had coalesced to form a deep-rooted mistrust of the Alliance.

While Russia’s worsening view of NATO between 2007-2009 can easily be attributed to the Alliance’s role in the Georgian War, it does not explain why public opinions of America and the European Union improved during this time, especially given the high correlation between opinions of America and NATO. Of course, it is always difficult to distinguish between contribution and attribution when analyzing public opinion polls, but while any explanation calls for speculation, it seems very possible that the dual elections of Barack Obama and Dmitri Medvedev provided enough of a positive boost to overcome the negative effects of the war. It seems clear in this instance that NATO’s actions were not the tail that wagged the dog when it came to Russian views of America. But what about the opposite effect? Does America’s popularity (or unpopularity) among the Russian public influence opinions of NATO?

The time period between 2009-2010 would seem to suggest that, yes, the actions of the United States can have a profound impact on Russian views of NATO. In 2010, favorable views of the U.S. and NATO improved by 13% and 16% respectively compared to favorable views in 2009. During that same stretch, Russian opinion of the EU remained static. This can partly be explained by Russia’s already favorable views of the EU at the time (69% of respondents had favorable views in both years), but it still suggests that events in America had more of an impact on views of NATO than events in Europe. While it again requires speculation, it seems likely that the thawing of U.S.-Russia relations, highlighted by the signing of a nuclear reduction treaty and the shelving of American-led plans to install a missile-defense shield in Central Europe, was the primary cause of the improved attitudes towards both the United States and NATO. While it is possible that NATO’s decision to reestablish high-level contacts with Russia contributed to the improved view of the Alliance, it seems unlikely to have caused such a significant bounce in favorable opinions. In this case, NATO seems to have enjoyed the global goodwill brought forth by the Obama Administration’s efforts to bridge the transatlantic divide. But while the thawing of U.S.-Russia relations in 2009 seems to have directly improved the Russian public’s views of NATO, did it have any impact on the Russian media’s coverage of the Alliance?

TABLE 4.1

CHRONOLOGY OF KEY NATO, RUSSIA, AND U.S. EVENTS BETWEEN 2007-2010

2007

- (November) Putin signs law suspending Russian participation in the 1990 Conventional Arms Treaty

- (December) Putin’s United Russia party wins election; Western observers criticize the fairness of the elections

2008

- (March) Dmitri Medvedev wins presidential election

- (April) Putin remains in power as Prime Minister; Tensions rise in Georgia over Russian minorities in Abkhazia and South Ossetia

- (April) Albania and Croatia formally invited to join the Alliance at the Bucharest Summit; decision on Georgia and Ukraine deferred until December

- (May) NATO opens new cyber defense center in Estonia, which previously blamed Russia for weeks of cyber-attacks against its Internet structure

- (August) Russia invades Georgia; NATO temporarily suspends formal diplomatic contact with Russia and declares there will be “no business as usual…under present circumstances” (Jaap de Hoop Scheffer as qtd. by Shuster 2008)

- (September) NATO delegation visits Georgia and criticizes EU-brokered ceasefire deal for allowing Russian forces to remain in Abkhazia and South Ossetia

- (November) President Medvedev announces that Russia will deploy short-range missiles in Kaliningrad to counter America’s proposed missile shield in Central Europe

- (November) Barack Obama wins U.S. election

2009

- (January) Barack Obama inaugurated as 44th U.S. president

- (January) Russia stops gas supplies to Ukraine over unpaid debts; Russia halts plans to place missiles in Kaliningrad citing change in American leadership

- (March) Hilary Clinton presents misspelled “reset” button to Sergei Lavrov

- (March) NATO declares that high-level contacts with Russia will resume after 60th Anniversary Summit

- (April) NATO’s 60th Anniversary Summit sees the inclusion of Albania and Croatia into the Alliance

- (July) In a move aimed at replacing the 1991 Start 1 treaty, President Medvedev and Barack Obama reach an outline agreement to reduce their countries' stockpiles of nuclear weapons

- (September) U.S. suspends plans to place missile defense bases in Poland and the Czech Republic

- (July) Anders Fogh Rasmussen takes over as NATO Secretary General

2010

- (April) Presidents Obama and Putin sign new Start Deal to reduce nuclear arsenals

- (June) President Medvedev visits the White House for the first time

- (November) Under Fogh Rasmussen’s direction, a new "strategic concept" is completed at the NATO summit in Lisbon. The meeting also reaches agreement on establishment of missile defense shield in Europe, reaching a new level of understanding with Russia in the process

RUSSIAN MEDIA PORTRAYAL OF NATO

In order to test the all important framing of NATO issues in the Russian media, a limited content analysis of RT’s coverage of NATO between 2009-2010 (the peak of Russian favorable opinion towards NATO) was performed. For a means of comparison, a sample of RT’s coverage between 2013-2015 (the nadir of Russian favorable opinion towards NATO) was also analyzed. The question tested was whether or not the coverage between 2009-2010 would reflect the general attitude of the public; that is, would it be more favorable towards NATO than the coverage between 2013-2015.

Before addressing the results, it is important to provide some background on the Russian media. Russia supports its messaging efforts through a variety of mediums, including RT (formerly Russia Today), a slickly-produced, English-language satellite television network (Sinikukka 2014). In the past decade, the Kremlin has also launched dozens of radio stations and websites, including Sputnik, an English-language site giving a pro-Kremlin, anti-U.S. take on the news. The Russian government has invested heavily in these initiatives: it spends an estimated $1.4 billion dollars a year to disseminate their narratives to an audience of 600 million people across 130 countries in 30 different languages (Ziff 2015).

Studies of the Russian media’s framing of NATO have also shown that NATO issues have always been framed in strongly negative terms (Black 2000; Zimmerman 2002). This was especially true in the aftermath of the annexation of Crimea and the downing of Malaysia Airlines flight 17 when Moscow’s strategy was to “fill the domestic airwaves with so many bizarre rumors, conspiracy theories, and paranoid fantasies that a cynical public stops caring what really happened” (Bayles 2014). In a speech at the NATO Public Diplomacy Forum in 2015, NATO Deputy Secretary General Ambassador Alexander Vershbow voiced concerns over the current state of the Russian media:

“We have become used to Russian propaganda: an endlessly changing storyline designed to obfuscate and confuse, to create the impression that there are no reliable facts and therefore no truth. We saw this technique used after the shooting down of the Malaysian airliner last July. We have seen it in the use of fabricated pictures and fake atrocity claims, in the constant lies and the accusations that any Western criticism of Russian leaders is ‘inciting anti-Russian hysteria’” (Vershbow 2015).

MEDIA ANALYSIS RESULTS

In order to compare RT’s coverage of NATO, 20 videos (10 from 2009-2010 and 10 from 2013-2015) were randomly selected from RT’s YouTube channel using the search word “NATO.” Each video was ranked as positive, negative, or neutral depending on its coverage of the Alliance. Rankings were determined by the language used to describe the organization, the context, the visual framing, and the video’s title.

In all ten videos viewed from 2013-2015, RT’s coverage of NATO was deemed “negative.” A sampling of video titles included: “More NATO troops in E Europe: ‘Increasing tension to justify existence;’” “Ukraine joining NATO could trigger all out war;” and “Massive NATO military drills near Russia’s border are underway.” Given RT’s connection to the Kremlin, the lack of neutrality in RT’s post-Crimea coverage is hardly unsurprising. But what about during the reset? While the majority of the videos viewed were still “negative” towards NATO (6 out of 10), there was a definite shift in the overall tone. Four of the videos were deemed neutral, providing coverage that could be considered “fair and balanced” (Entman 2004). Those neutral videos included: “NATO: US anti-missile plans shelving a positive step;” and “Russia, Alliance re-launch co-op.” The results are hardly significant given the limited sample size; however, as a snapshot, they do suggest that the positive feelings engendered by the Obama-Medvedev reset carried over into the media.

CONCLUSION: NATO PUBLIC DIPLOMACY TOWARDS RUSSIA

In conclusion, the findings in this paper generally support a long-held axiom of public diplomacy practitioners: public diplomacy cannot overcome unpopular policies. Or, to use the words of NATO’s Deputy Secretary General Ambassador, Alexander Vershbow, “Actions will always speak louder than words” (Vershbow 2015). That, however, is not to suggest that NATO’s messaging cannot and does not have an affect on Russian public opinion.

This paper, in fact, was originally intended to provide quantitative data that could be used to evaluate the successes of NATO’s various strategic messaging campaigns directed at the Russian public. Unfortunately, the irregularity of polling data and the general framing of the questions posed to the Russian public did not allow for a meaningful evaluation of NATO’s public diplomacy work. Therefore, this section cannot provide the hard data necessary to support claims that NATO’s public diplomacy work has been ineffective at winning the proverbial ”hearts and minds” of the Russian public. At the same time, as a scholar of public diplomacy, it seems warranted for me to provide at least a cursory critique of NATO’s current approach towards countering Russian propaganda and negative messaging.

In a speech before the 2015 NATO Public Diplomacy Forum in Brussels, Alexander Vershbow stressed the importance of Russia vis-à-vis NATO’s public diplomacy objectives when he stated that the Alliance “must continue to rebut Russian propaganda: not by engaging in tit-for-tat, but by deconstructing propaganda, debunking Moscow’s false historical narrative, by exposing the reality of Russia’s actions, and by restating the international rules it is breaking” (Vershbow 2015).

Vershbow’s message is inherently contradictory: he warns against engaging in a “tit-for-tat” war of words, while at the same time championing steps that will inevitably do just that. His comments in Brussels echo similar comments made a year earlier when he stated, “Clearly the Russians have declared NATO as an adversary, so we have to begin to view Russia no longer as a partner but as more of an adversary than a partner” (Vershbow as qtd. by Klimentyev 2014). Both of these statements, if viewed through a Russian lens, seem to inflame tensions. By focusing on exposing Russian propaganda, NATO is missing what scholars consider to be the key tenet of effective public diplomacy: listening (Cull 2008). By simply dismissing or “debunking” Russian grievances – legitimate or otherwise – Vershbow provides fodder for those in Russia who believe that the West in general, and NATO in particular, has been dismissive of their concerns.

This point extends to one of NATO’s most publicized responses to Russian criticism: a document entitled NATO-Russia: Setting the Record Straight. The document responds to Russian “claims,” including, as was discussed earlier, NATO’s flat rejection of Russia’s belief that it was misled in regards to the Alliance’s plans for eastward expansion. The paper bluntly asserts that “no such promise was ever made, and Russia has never produced any evidence to back up its claim” (NATO-Russia 2015). This hardline approach seems to be misguided. At this point, proving the nebulous “facts” should be far less important than dealing with the reality of the perception. For a quarter-century, Russians – rightly or wrongly – have believed that Brussels and Washington reneged on their collective promise not to expand NATO into former Warsaw Pact countries. Any attempt to alter that belief, or any number of other long-held beliefs, is likely to provoke an adverse reaction.

NATO’s public diplomacy strategy vis-à-vis Russia, therefore, seems tailored to Alliance members and western audiences that are predisposed to anti-Russian sentiments. If that is, in fact, the target audience, then NATO’s messaging strategy may have some positive effect in terms of rallying support for the Alliance. If, however, the intention is to “engage and influence” (Cull 2005) the Russian public, NATO’s top-down, one-way approach will likely prove ineffective. Moving forward, NATO would be better served by engaging the Russian public in a constructive dialog regarding areas for future cooperation, rather than rehashing long-festering grievances. To that end, it is important that the Alliance and Russia find some common ground – whether it be counterterrorism or peacekeeping – that will allow NATO to formulate an identity divorced from its Cold War origins.

While this paper suggests that no amount of effective public diplomacy is likely to overcome the current geopolitical rift, it does offer some hope that a change in the geopolitical dynamic (as occurred between 2009-2010) can, eventually, improve Russian opinions and media coverage of the Alliance. Given that Russia remains one of the world’s greatest nuclear superpowers, the threat caused by cleavages between NATO and Russia is perhaps even greater now than it was during the relative stability of the Soviet Union (Norris 2005). For that reason alone, NATO should expend considerable energy towards improving its relationship with the Kremlin, and its messaging towards the Russian people.

WORKS CITED

Ahmed, Saeed. “Vladimir Putin's approval rating? Now at a whopping 86%.” CNN Online (26 February, 2015).

Antonenko, Oksana. “Russia, NATO and European Security After Kosovo.” Survival 41, 4 (Winter 1999-2000).

Bayles, Martha. “Putin’s Propaganda Highlights Needs for Public Diplomacy.” Hudson Institute Online. Available Online.

Black, J.L. Russia Faces NATO Expansion: Bearing Gifts or Bearing Arms? Lanham (2000). Cambridge (2008).

Cull, Nicholas J. The Cold War and the United States Information Agency.

Entman, Robert. Projections of Power: Framing News, Public Opinion, and U.S. Foreign Policy Chicago (2004).

Felgenhauer, Pavel. “NATO’s Ineffective Charm.” The Moscow Times (23 January, 1997).

Gerber, Theodore. “Foreign Policy and the United States in Russian Public Opinion.” Problems of Post-Communism 62, 2 (March 2015): 98-111.

Gorman, Eduardo B. NATO and the Issue of Russia. New York (2010).

Goldsmith, Benjamin E. and Horiuchi, Yusako. Does Foreign Public Opinion Matter for U.S. Foreign Policy? World Politics 64, 3 (July 2012).

Holsti, Ole R. Public Opinion and American Foreign Policy. University of Michigan Press. Ann Arbor (2004).

Klimentyev, Michael. “Russia Now an Adversary, NATO Official Says.” Associated Press (1 May 2014).

Kramer, Mark. “Russian Policy Towards the Commonwealth of Independent States: Recent Trends and Future Prospects.” Problems of Post-Communism 55, 6 (November/December 2008): 3-19.

Mearsheimer, John. “Why the Ukraine Crisis is the West’s Fault.” Foreign Affairs (September/October 2014). Online.

NATO. “Russia’s Accusations: Setting the Record Straight.” April 2016. Available Online. http://nato.int/cps/en/natohq/115204.htm

NATO. “NATO-Russia Relations: The Facts.” December 2015. Available Online. http://nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_111767.htm?#cl303

NATO. 2010-2011 NATO Public Diplomacy Strategy. 2011. Available Online. https://info.publicintelligence.net/NATO-PublicDiplomacy-2011.pdf

“NATO Publics blame Russia for Ukrainian Crisis but Reluctant to Provide Military Aid.” Pew Research Center (2015). http://www.pewglobal.org/2015/06/10/nato-publics-blame-russia-for-ukrainian-crisis-but-reluctant-to-provide-military-aid/russia-ukraine-report-39/

Norris, John. Collision Course: NATO, Russia, and Kosovo. Westport (2005).

Nye, Joseph S. “Public Diplomacy and Soft Power.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 616, 1 (March 2008); 94-109.

Otkay, Emel G. “Transformations of NATO and Increasing Role of Public Diplomacy.” International Relations 9, 34 (2012): 125-149.

Ponsard, Lionel. Russia, NATO and Cooperative Security. London (2006).

“Russia Votes: International Security.” The Levada Center (2008). Available Online. http://www.russiavotes.org/security/security_usa_nato.php

Saari, Sinikukka. “Russia’s Post-Orange Revolution Strategies to Increase its Influence in Former Soviet Republics: Public Diplomacy Po Russkii.” Europe-Asia Studies 66, 1 (2014): 50-66.

Sarotte, Mary Elise. “A Broken Promise: What the West Really Told Moscow about NATO Expansion.” Foreign Affairs (September/October 2014). Available Online.

Saunders, Jeremy C. “Improving US-Russian Relations Through Peacekeeping Operations.” Harvard University (November 2009).

Shuster, Mike. “NATO: ‘No Business as Usual with Russia.” National Public Radio Online (8 August 2008).

Treisman, Daniel. “Presidential Popularity in a Hybrid Regime: Russia Under Yeltsin and Putin.” American Journal of Political Science (September 2010).

Vershbow, Alexander. “Meeting the Strategic Communications Challenge.” 2015 NATO Public Diplomacy Forum (17 Feb 2015).

Voronin, A.I., “Russia-NATO Strategic Partnership: Problems, Prospects.” Military Thought (English Language Version of Voyennaya Mysl), No. 4 (2005): 23.

Ziff, Benjamin. “Testimony Before the SFRC Europe Subcommittee.” 3 Nov, 2015. http://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/110315_Ziff_Testimony.pdf

Zimmerman, William. The Russian People and Foreign Policy: Russian Elite and Mass Perspectives, 1993-2000. Princeton (2002).

[1] See Table 2 as well as: http://www.pewglobal.org/2015/06/10/nato-publics-blame-russia-for-ukrainian-crisis-but-reluctant-to-provide-military-aid/russia-ukraine-report-39/

[2] See Table 3 as well as: http://www.pewglobal.org/question-search/?qid=837&cntIDs=@41-@41.5-&stdIDs=

[3] 2010-2011 NATO Public Diplomacy Strategy: https://info.publicintelligence.net/NATO-PublicDiplomacy-2011.pdf

[4] See Table 1.1 as well as Pew Research Center Data http://www.pewglobal.org/2015/06/10/nato-publics-blame-russia-for-ukrainian-crisis-but-reluctant-to-provide-military-aid/russia-ukraine-report-39/

[5] Source: January 1997 ROMIR Omnibus Survey as referenced in Zimmerman (2002)

[6] Source: January 1997 ROMIR Omnibus Survey as referenced in Zimmerman (2002)

[7] See http://janda.org/c10/Lectures/topic06/L24-significanceR.htm for a more detailed explanation of correlation coefficients

[8] See http://www.oneonta.edu/faculty/vomsaaw/w/psy220/files/SignifOfCorrelations.htm for an explanation of statistical significance