Huffington Post readers may be familiar with Arianna Huffington’s campaign to redefine success away from the two metrics of money and power toward a third which includes well-being, wisdom, and our ability to wonder and give...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Culture Posts: Who is the Public in Public Diplomacy?

Over the past decade there has been a near universal surge of interest in public diplomacy. Yet, as more nations venture into the PD realm it is becoming increasingly clear that understandings of PD concepts and practices are anything but universal. One area where different views are emerging is the role of the public. Who is the “public” in public diplomacy?

Not long ago the answer was so obvious that the question was not even asked. Today, we need to ask such basic questions. It is not just that nations may see public diplomacy differently. It is also likely that their publics see it differently as well.

Rather than try to merge these different perspectives into one universal view, the goal of Culture Posts has been to explore hidden cultural assumptions to see what can be learned from them. As we see in the case of “Who is the public?” the PD assumptions of other nations often expose the vulnerable blind spots in one’s own PD approach.

Who is the “Public” in Public Diplomacy?

Up until recently, the “public” in public diplomacy meant foreign publics. In her extensive review of PD scholarship, former CPD Fellow, Kathy Fitzpatrick found “divergent views" on public diplomacy, but “widespread agreement” that it involved foreign as opposed to domestic publics.

The assumption of foreign publics was echoed in early PD definitions. In 1997, public diplomacy goals entailed “informing, influencing and understanding foreign audiences.” Even the more recent concepts of public diplomacy that stress relationship-building and engagement are about connecting to foreign publics, not one’s own domestic public.

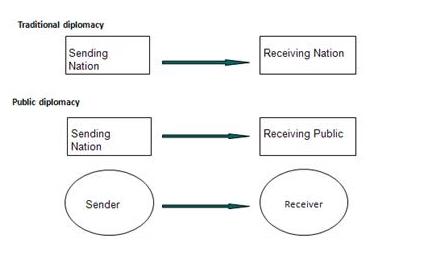

The assumption that the public is foreign or the Other resonates with dominant views of diplomacy and communication. Both play critical roles in representation (diplomacy) and transmitting information (communication) that help link individual entities and the larger society.

In traditional diplomacy, representation is between Sending nation and Receiving nation. In public diplomacy, this paradigm becomes the Sending nation and the Receiving public. In communication, the Sender transmits and exchanges messages with the Receiver.

The terms “sending” and “receiving” is revealing. The hidden assumption is that the intended receiver is the Other. Why would one send or represent something to one’s self?

Yet, one may ask, why is there the assumption that entities need to send or receive anything – unless there is the parallel assumption of separate, autonomous individuals?

What has not been readily acknowledged in the PD literature is the link between the U.S. and U.K. dominance in the PD field and the ideal of individualism. Individualism presupposes a world of separate, autonomous individuals. While many societies share the value of individuality (distinctiveness), not all share the assumption of individualism (separateness). These different assumptions produce different perspectives about the public.

Relational Spheres

In several Asian and African countries, the domestic as well as diaspora publics assume a prominent and even foundational role in the nation’s PD initiatives. China, for example, focused on its domestic public as the first point of contact for foreign visitors to the 2008 Olympics in Beijing. Other countries, such as Colombia, Indonesia, and South Africa launched their nation branding initiative with a domestic component.

The assumption that public diplomacy begins with the closest rather than the farthest public may have its origin in a relational view of communication. Relationalism assumes that individuals are not autonomous by nature but presumed to be linked to others.

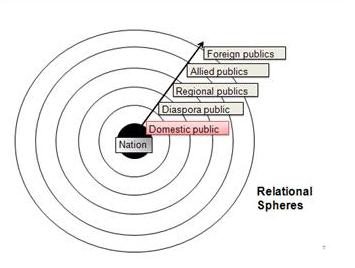

Chinese scholar Fei Xiaotong spoke of concentric circles of interpersonal and social relationships, which like the ripples of water, radiate out from each individual. These circles overlap with those of others.

The idea of concentric circles or “relational spheres” highlights the natural processes and patterns of existing relationships. Communication and diplomacy work primarily through these existing relationships rather than working to create relations.

It is possible to envision the relational spheres of a nation. The most important, or privilege relation is the domestic public. The domestic public is followed by the diaspora, then the close regional or affinity publics, then the geographical or ideological distant publics to ultimately the generic global public. The foreign public is the most distant public.

From this perspective, as Ellen Huijgh described it: “Successful public diplomacy begins at home.”

Learning from Differences: Blind Spots

What we can learn from the different assumptions about who is the public?

For one, we can expand the vision of public diplomacy. The more we know about how public diplomacy is viewed from different perspectives, the more comprehensive our understanding becomes. Second, it is not just how other nations view public diplomacy differently. It is likely that publics may hold different assumptions about public diplomacy as well.

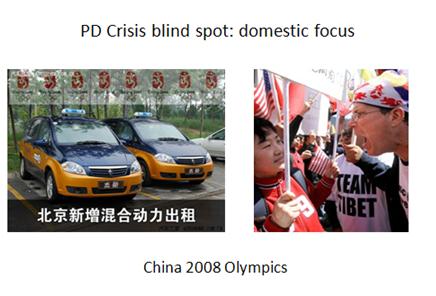

Developing a more diversified and comprehensive view can be particularly valuable when assumptions become “blind spots.” Nations are most vulnerable to their blind spots during crisis or high-stress scenarios. Under stress, the tendency is to fall back on what is familiar. Two such crisis PD scenarios are illustrative.

The first instance of crisis blind spot comes from focusing too closely on the domestic public. As the host of the 2008 Olympics, China’s focused intensively on preparing its domestic public to properly receive the expected foreign visitors. The attention to detail extended purportedly down to the color of the shirts worn by the Beijing taxi drivers. However, China appeared blindsided by the actions of foreign publics during the Olympic torch relay outside China.

The second example of a blind spot comes from overlooking the domestic public. In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, U.S. public diplomacy launched several initiatives aimed at foreign publics in Islamic world. Included was a high profile campaign called “Shared Values.” While the campaign sought to showcase religious tolerance in America, opinion polls revealed anti-Islamic sentiment was on the rise within the U.S. domestic public.

Over the years, U.S. and Chinese public diplomacy have tried to address the vulnerabilities exposed by their limited view of “the public.” China appears to have developed a keener interest in “discourse power,” as a means to develop a stronger voice that can communicate (transmit information) directly to foreign publics. U.S. public diplomacy has incorporated more relational initiatives that emphasize the link between its domestic and global publics.

Through an expanded vision of “the public,” both nations appear to be developing a more comprehensive and effective PD approach that can accommodate the diversity of views of relations between nations and publics.

Expanding the Vision of Publics

As other nations add their perspectives to the practice of public diplomacy, the field has the opportunity to expand its vision. Even better than acknowledging the legitimacy of the diverse perspectives of domestic publics is learning from them. An expanded vision of “the public” may be one of the keys to developing a more effective, global approach to public diplomacy. In a future Culture Post, I hope to look at five critical roles of the domestic public in public diplomacy.

* This Culture Post is based on a presentation at the recent Association of Public Diplomacy Scholars conference “Public Diplomacy on the Frontlines” held at the Center on Public Diplomacy, May 3, 2013.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

December 4

-

December 12

-

December 16

-

January 6

-

December 2

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.