With the ever-growing influence of social media on our day-to-day lives, it is not surprising that world leaders have made it an important part of their engagement with the public. Pope Francis issues tweets in nine...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Digital Diplomacy and the Bubble Effect: The NATO Scenario

Measuring the impact of digital diplomacy using quantitative metrics (number of followers, retweets, shares, likes and so on) has become a general practice among Ministries of Foreign Affairs (MFAs), and for good reasons. Quantitative indicators allow MFAs to see how far their message travels online (via the number of followers), how well it is received by the target audience (via the number of shares and likes) and how deeply it resonates with online communities (via the number of retweets). More sophisticated techniques calculate the lifespans of tweets, determine differences in interaction when posts are in local languages, and compare and contrast the success of various digital diplomacy campaigns.

While these methods do not directly measure influence in terms of perception or attitudinal shifts of the target audience, they nevertheless provide reasonably good proxy indicators for such mutations. However, the reliability of their conclusions much depends on a critical assumption about the nature of the population that is being observed—namely, that the latter is sufficiently diverse in its political views relative to the source of digital information. In other words, the MFAs’ digital communication campaigns are presumed not to merely “preach to the choir” of sympathetic followers, but to actually reach constituencies outside the self-reinforcing “bubble” of like-minded followers.

The academic term used to describe the tendency of individuals to associate and bond with like-minded persons is called homophily. Sociology has long confirmed the significance of homophily in the constitution of social groups, either as status homophily, in which similarity is based on informal, formal, or ascribed status (shaped by race, ethnicity, gender, age, religion), or as value homophily, which is based on values, attitudes, and beliefs (Lazarsfeld & Merton 1954). Recent studies have also found that homophily has an impact on the way in which online social networks develop, to the extent that topical similarity could capture actual friendship with 92% accuracy. These findings are perhaps not that surprising given the fact that the very business concept of some social networks such as Facebook is explicitly based on the idea of homophily (e.g., by enabling users to connect with their friends and with the friends of their friends). What is less clear though is how relevant homophily is for digital diplomacy and whether it is important to escape its pull.

Homophily may prevent NATO from engaging with those constituencies that are particular important for defusing tensions in areas of strategic importance (e.g., online users in Russia or in the Middle East).

In an effort to address these questions, I decided to examine the potential impact of homophily on NATO’s Twitter account (344,920 followers, as of Mar 2, 2016). Methodologically, I conducted this analysis in two steps. First, I used Twitonomy to collect 3,002 tweets posted by @NATO and retweeted by its followers from Feb. 28 to Mar. 3, 2016. The automatic geo-location of the tweets generated two maps of NATO followers, one global and one regional (see Fig 1 and 2). Geolocation is a relatively good method for mapping followers as it circumvents the problem of guessing the identity of Twitter users based on vague and often unreliable bio descriptions. The maps revealed that the online conversation generated by NATO via its Twitter account overwhelmingly involved audiences in the member and partner states (North America, Europe, Turkey) and only marginally in countries outside NATO’s core area of influence. Most surprisingly, the maps showed NATO to be minimally engaged with the Russian public, an interaction one would expect to take place more intensely given the current strained relationship between NATO and Russia.

Fig 1: Global geolocation of NATO followers

Fig 2: Geolocation of NATO followers in Europe/Middle East/Asia

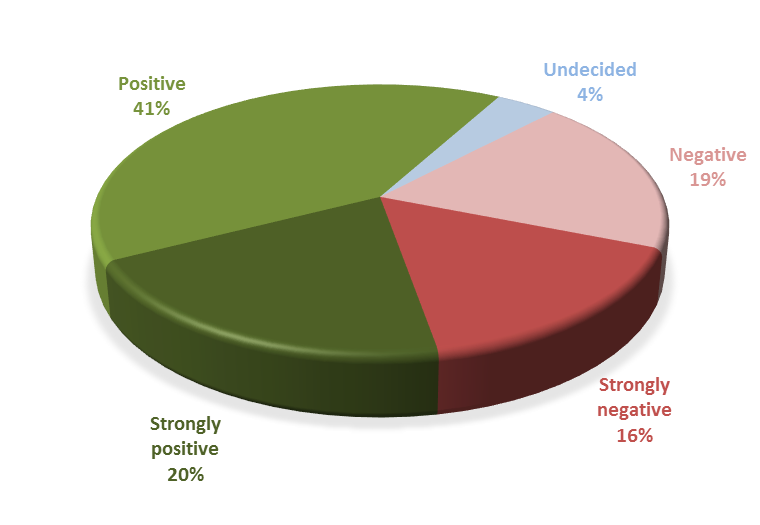

In a second step, I conducted sentiment analysis on a sample of 100 tweets from the entire data set on the assumption that a balanced or negative set of opinions against NATO would challenge the presence of homophily, while a strong show of positive attitudes would validate it. The results clearly indicated that NATO followers were overall sympathetic to messages posted by NATO in the four day period of research and by a significant margin (see Fig 3). This finding provides extra support to the conclusion drawn above from the two maps about homophily playing an important role in development of NATO’s social network. It should also be added that the scope of homophily can be more precisely determined by in-depth statistical analyses of the social-demographic characteristics of NATO followers (status homophily) and/or by longitudinal content analysis of their posts and comments (value homophily).

Fig 3: Sentiment analysis of NATO tweets and retweets

That being said, to what extent is it important for NATO to step outside the “bubble” of like-minded followers and reach out to unfamiliar constituencies? On the one hand, NATO has a clear duty to its members and partners to keep them informed about its activities and to provide political and military reassurance, especially in times of crisis. Therefore, high levels of online like-mindedness might not be that detrimental to NATO’s public diplomacy and digital outreach efforts, simply because homophily can make easier for NATO to disseminate its messages with minimal obstructions and to retain the confidence of its core audience. On the other hand, homophily may prevent NATO from engaging with those constituencies that are particular important for defusing tensions in areas of strategic importance (e.g., online users in Russia or in the Middle East). In other words, a careful balance must be struck between the imperative to maintain a healthy level of popular support in NATO countries and the need to engage with audiences of strategic relevance for NATO’s security agenda (e.g., by opening Twitter accounts in local languages and tailoring messages to events relevant for the target audience).

Photo by Eric Fischer I CC 2.0

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 2

-

December 15

-

December 17

-

December 17

-

November 25

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.