Simon Anholt is an independent policy advisor to the Heads of State and governments of 57 countries. He publishes the Good Country Index, which ranks countries on their contribution to humanity and the planet. He also...

KEEP READING

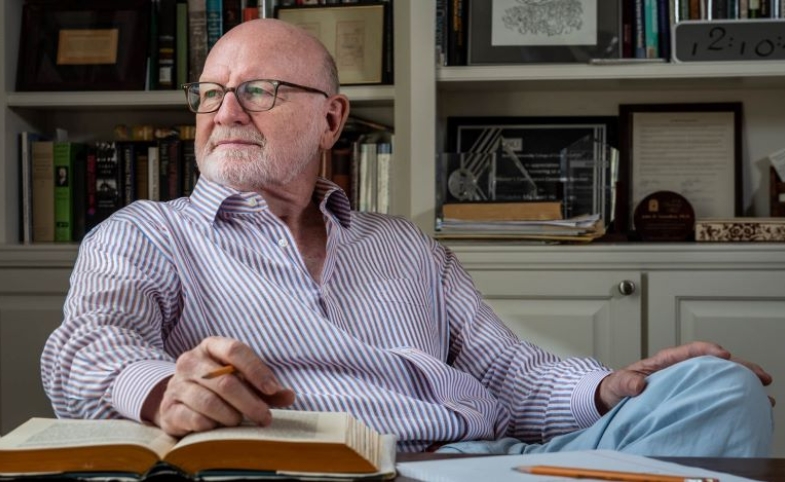

Meet the Author: John Maxwell Hamilton

John Maxwell Hamilton is the Hopkins P. Breazeale Professor of Journalism in the Manship School of Mass Communication, Louisiana State University, and a global fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars. He was previously a journalist, working chiefly on foreign affairs, and on the staffs of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and the World Bank. He is the author of seven books, including Journalism’s Roving Eye: A History of American Foreign Reporting, which won the Goldsmith Prize. His latest book, Manipulating the Masses: Woodrow Wilson and the Birth of American Propaganda, is now available.

How did the idea of a history of the Committee on Public Information (CPI) come to you, given that a lot has been written about the agency and its work?

True, histories of World War I frequently discuss the Committee on Public Information. But assertions about the CPI have been built on a small number of studies, none of which constitutes a complete, documented history. With this in mind I began with the assumption that, in order to piece together what the CPI did, it was essential to go beyond the limited CPI files in the National Archives.

This exploration brought to life aspects of the CPI that had received little or no attention, for instance, the CPI’s management style, which was a mix of brilliant entrepreneurship and chaos; its use of front organizations; its fight to take control of over-the-trenches American military propaganda in Europe and its failure to follow through when it was in charge; congressional efforts to rein in the CPI; the CPI’s bizarre post-war activities in Europe; and the closure of the CPI at a time when it, or a successor organization, could have helped Wilson’s achieve his peace goals.

Also, I came to realize that a full understanding of the CPI depended on taking account of the Democratic National Committee’s publicity bureau in Wilson’s 1916 reelection campaign, which was a test kitchen for the CPI, and on showing the CPI’s relationship to propaganda undertaken by other belligerent nations.

You write in your book: “The control of propaganda is one of the thorniest problems of democracy… Government information can either sustain democracy or destroy it.” How does government information possess such wide-ranging power in a democracy?

The government’s communication powers are like the plant deadly nightshade, which can promote sanity or bewitch, depending on how the potion is administered. The government produces vast amounts information – scientific studies, socio-economic data, maps, advisories, and the list goes on. These help citizens arrive at better personal decisions and as well as better-informed policy preferences. Government transparency about its activities is also essential. We need to know what contracts the government awards and what rules it writes. (To its credit, the CPI advanced this by creating the forerunner of the Federal Register). Finally, we want our elected leaders to personally make the case for the policies they wish pursue. That is essential to the deliberative process.

But we do not want our presidents to use the ever-growing federal information apparatus – which is meant to provide facts – to change our views. The line between wholesome and pernicious information is not always easy to draw. Even so, more could be done. Laws to fence back propaganda are wholly inadequate, and the few that do exist are rarely enforced.

Could you explain how government propaganda and “the credibility gap” increased cynicism following World War I?

We commonly mark the Vietnam War as the moment when cynicism about government took a turn for the worst. But disappointment over the Great War brought forth an equally powerful surge of cynicism that would be built on over time. The war arrested and to some extent reversed domestic reform. Wilson did not achieve the postwar goals he promised when he took the country into war. The press realized it had been used and became more suspicious of government. Books poured forth showing that propaganda had built up false expectations and had covered up facts that needed to be known. “Every new book destroys some further illusion,” progressive writer Frederic Howe lamented. “My attitude toward the state was changed. I have never been able to bring it back. I became distrustful of the state.”

What propaganda patterns did the CPI establish that persist today?

There are quite a lot. Even the use of contemporary social media has an antecedent in the CPI, as evidenced by the Four Minute Men. Those speakers, 75,000 strong, spoke on CPI-directed themes in movie theaters during the changing of reels during intermission. The experience for a movie-going American was like that of Americans today when they look at their cell phones for a little amusement and receive political message they had not asked for.

In addition to the government’s building on CPI techniques with ever-greater sophistication, we can see a continuation of attitudes. One of those is that only the other side uses propaganda. Propagandists always deny they are propagandists and always claim they are faithful to facts. That is an iron law of propaganda. So is the irresistible urge to use the power propaganda provides, when it is available.

What surprised you in researching and writing this book?

Here is an overarching one, building on what I just said above: The CPI’s history is not a story of bad people doing bad things, but of good people who used emotion, coercion, and tendentious facts to get the results that they wanted, no matter that it short-circuited the very democratic processes they claimed to be protecting. Muckraker George Creel, the hyperkinetic head of the CPI, confessed in a moment of great clarity after the war, “With the existence of democracy itself at stake, there was no time to think about the details of democracy.”

Why is Manipulating the Masses crucial reading for students of public diplomacy?

I would never presume to say that anything I wrote was crucial reading for anyone. What I can say is this.

First, I tried to the best of my ability to provide deeply researched detail on the origins of government propaganda.

Second, I wanted to show how easy it is for a president to push the boundaries of government propaganda power. It is a not a great stretch to go from President Wilson suppressing unwelcome comment by calling it “enemy talk” to President Trump calling inconvenient facts “fake news” – and falsely declaring he has won reelection while “Hail to the Chief” plays in the background.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

Popular Blogs

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

January 2

-

January 8