The CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

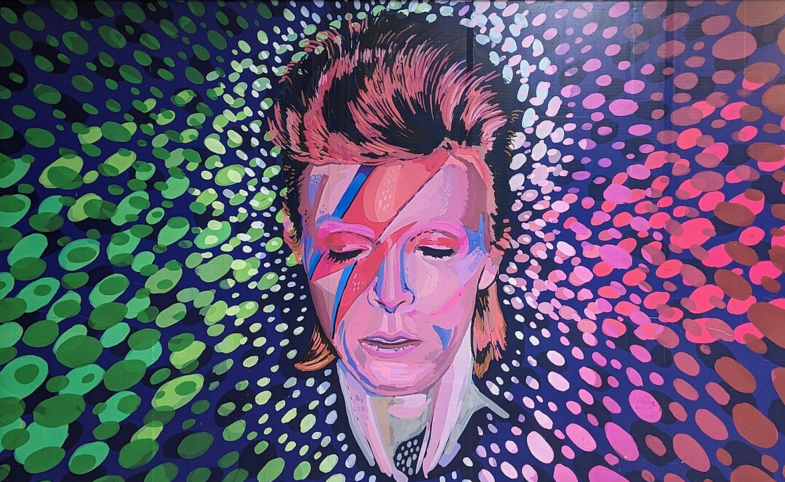

Heroes of the Wall

When David Bowie took the stage in front of a crowd of almost 80,000 West Berliners, it was quite a momentous occasion. The stage, which had been erected on the Platz der Republik, an open square in front of the Reichstag, hosted the Concert for Berlin, a celebration of the 750th anniversary. Berlin was a city divided, and the concert was being held only a few hundred meters from the Berlin Wall. This was no mere coincidence; the concert was a carefully orchestrated act of public diplomacy. Through David Bowie’s cultural appeal, West Berlin organizers sought to reach East Berlin's youth, thereby weakening the GDR's hold on its people. Drawn by Western radio broadcasts and word of mouth, thousands gathered on the other side of the wall for the concert stage. Through sound diplomacy, soft power, and authenticity, this concert served as a showcase of effective public diplomacy.

This article examines the Concert for Berlin not only as a significant cultural moment but also as a turning point in German unity. The use of Bowie’s cultural capital, leveraging his status as an “Honorary Berliner,” allowed the messaging to circumvent the usual cynicism associated with state-sanctioned communication. Coming from Bowie, the messaging felt more authentic to the audience, eliciting a passionate response. This case study also highlights the fallout from the concert, the dilemma that arose within the GDR, and the failed attempts to contain citizen discontent. The Concert for Berlin ultimately highlighted the immense power of cultural ideals. It is possible to erect barriers and stop physical movement, but it is impossible to prevent the spread of ideas. Through the spread of culture and ideas, the foundation was built for what would eventually lead to the fall of the Berlin Wall two years later.

A City Divided

The year 1987 marked a historic milestone for Berlin. Celebrating its 750th anniversary, the once-unified city had been divided by the Berlin Wall, with each half operating under opposing political ideologies. At the heart of the Cold War, both East and West Berlin sought to carve out distinct identities while actively working to delegitimize the other. East Berlin served as the capital of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the communist state established in the Soviet-occupied zone following the Second World War. On the other hand, the Western sectors, which had been occupied by the U.S., UK, and France, were now under the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), favoring free markets, democratic governance, and the integration of Western culture.

This ideological divide was even more prominently displayed during the anniversary celebrations. While celebrations took place on both sides of the Wall, they served an ulterior purpose: a contest for legitimacy. Both governments were keen to have their events outshine the other; a celebration that could resonate with those on the other side of the Wall would not only undermine the rival government's authority but also assert a greater claim to Berlin's true essence. This rivalry intensified amid growing discontent within the GDR. Facing economic stagnation and the repressive control of the Honecker regime, the East German population had grown increasingly disillusioned, a sentiment both sides recognized and sought to address through their respective festivities.

The Socialist Unity Party (SED), which was the ruling party in the GDR, sought to use the celebrations as an ode to their Prussian heritage, highlighting Berlin as the capital. In an attempt to celebrate continuity and highlight the city’s history, the regime reconstructed the Nikolai Quarters at the city’s medieval core. This did not connect with the disillusioned youth, however, as it failed to offer a vision for the future. The rigidity of the past was in sharp contrast to the desires of East Berlin youth. A generation that had become tired of the repression and control the GDR had over their lives and the culture they consumed, these youth were fascinated by the freedom and cultural diversity that the West offered.

The celebrations taking place in FRG were markedly different and organized around distinct ideals. In West Berlin, the celebrations echoed ideals of modernity and openness. Providing a cultural outlet through which Berliners could connect, the Concert for Berlin was organized. Placing the concert stage only a few hundred meters from the wall, in front of the Reichstag building, ensured that the sound would carry to the other side of the wall. The decision was also made to turn some of the speakers towards the Wall. In an attempt at “sonic diplomacy,” the organizers intended to permeate the physical borders and reach Berliners on the other side. Temporarily taking away the border between the Berliners, this was a calculated attempt at delegitimizing the SED’s control over its youth, as well as the culture it permitted.

The RIAS

Playing a significant role in the organization of this concert was the RIAS (Radio in the American Sector). Established following World War II, the RIAS operated from within West Berlin. Established to counter Soviet Propaganda, RIAS was one of the most widely listened-to radio stations in the GDR. Despite multiple attempts to jam RIAS broadcasts, East Germans would obtain uncensored access to news, music, and information through RIAS. For the youth, RIAS was one of the few connections to Western culture, and the concert organizers were well aware of this and exploited it.

The concert was held over three days: June 6, 7, and 8, 1987. For days beforehand, RIAS disseminated information about the time and location. By leveraging the captive audience, RIAS would play the performers' music and then announce the times they would go onstage. By broadcasting such information via radio, it was possible to circumvent the GDR’s physical borders and inform East Berlin youth when they needed to gather to listen to live performances. This was highly effective, as thousands began to congregate on the Eastern side of the wall on the day of the concert, around the same time the first songs started to play.

The Honorary Berliner

For any attempt at public diplomacy to succeed, the messenger's credibility is paramount. Given the concert's cultural and strategic importance, an artist had to be selected who would convey genuine authenticity rather than merely display manufactured solidarity. With this in mind, David Bowie was chosen to be the leading performer in the Concert for Berlin. Possessing enormous cultural capital, Bowie was not only one of the most acclaimed musicians in the world, but also someone who was considered an ‘honorary Berliner.’ Having lived in Berlin, Bowie understood the city's essence, having shared the isolation and separation that defined it. Bowie connected with the public in a way that no other visiting pop star or politician could.

Bowie’s stay in Berlin had a significant impact on his music. Moving there in 1976 in an attempt to escape the pressures of fame and rehabilitate a drug addiction, Bowie immersed himself in the culture very quickly. Living in a flat in Schöneberg from 1976 to 1978, Bowie recorded his critically acclaimed Berlin Trilogy, the albums Low, Heroes, and Lodger. Far from living in luxury, Bowie frequented working-class bars during his stay, taking in the essence of the city’s bleak artistic ethos.

For audiences on both sides of the Wall, David Bowie embodied authenticity. He was not an outsider commenting on the political situation, but a witness who had lived through it. The city had left an indelible mark on his work; the anthem Heroes emerged after he witnessed two of his friends kissing in the shadow of the Berlin Wall. To the East Berlin youth, Bowie was a credible narrator of their own reality. His return in 1987 was perceived as a homecoming, thereby granting him the moral authority to address the "friends on the other side" without appearing to be a calculated political provocation.

The Concert for Berlin

The location of the concert venue was just as important as the concert itself. A stage erected on the Platz der Republik, an open field situated directly in front of the Reichstag. The Reichstag, which had been such an essential monument to German history, now stood as a reminder of the division present within the nation. Although the building was then unused, its proximity to the Berlin Wall made it an appealing venue for the concert.

The concert was organized with consideration for listeners on both sides of the wall. Performers for the duration of the concert were briefed on the situation and informed of the concert's intended purpose. It has even been reported that David Bowie wanted to face all the speakers toward the wall, but due to logistical constraints, they were able to do so with only one-fourth of the available speakers. Using these speakers, they were able to maximize the spread of sound and permeate the physical barriers. In what can be considered an example of “sound diplomacy,” the organizers were able to take over East Berlin's auditory spaces. Through music, the barrier between the two parts of the city was less pronounced.

This was hardly the first time sound diplomacy had been attempted through the Berlin Wall. The wall, a physical embodiment of dominance, was not penetrable through physical means. To reach audiences on both sides, the only way is to use other means. Through sound, it offered opportunities to overcome this physical barrier and get to those on the other side. Sound diplomacy was demonstrated in 1961, years before the concert, when both sides of the wall used sound as propaganda. Through speakers mounted along the wall, the GDR played music insulting to the West when the chancellor of West Germany came to inspect the wall. West Germans responded with their own propaganda, deploying speaker vans along the wall and broadcasting into the East. In the first few years after the wall was erected, it was challenging to obtain Western newspapers in the East. During this period, loudspeakers broadcasting news from vans provided people with information about the outside world. West Berlin authorities targeted guards at the wall on the Eastern side during their auditory assault, trying to crack their loyalty and dedication towards the regime. The East would respond by playing folk tunes at full volume from their loudspeakers to drown out the news broadcasts. This back and forth highlights a new form of warfare being invented, one appealing to the emotions of people, rather than through weaponry and force. While these early attempts at sound diplomacy had some success, they were not at the level of the Concert for Berlin.

In this case, sound diplomacy established a shared space between people on both sides of the wall, defying physical boundaries. A shared experience, the wall could stop the physical movement of the people, but it could not stop the spread of culture. During this concert, the lines between permitted and forbidden became blurred as the SED faced a difficult decision about how to address this unwanted auditory intrusion. Whether East German authorities would be open to Western culture and permit its citizens to enjoy the spread of foreign culture, or would it be necessary to suppress citizens for defying authorities and attempting to listen to the music on the other side. One thing was certain: the people yearned for access to culture and information. Through sound diplomacy and strategic venue placement, they gained access to it.

As David Bowie got onstage in front of the Reichstag in front of over 70,000 people, it was a historic occasion. It marked the 750th anniversary celebrations for the city of Berlin; it was Bowie’s triumphant return to Berlin after over a decade; and there was an energy in the air. The location, in a place of such historical prominence, only added to that. Before he began performing, David Bowie decided to address those who had gathered on the other end of the wall, saying in German, “We send our best wishes to all of our friends who are on the other side of the Wall.” This direct acknowledgement broke down the psychological barriers between the two sides, momentarily uniting everyone.

Bowie’s set list was inspired by the Berlin Trilogy, with the songs that played embracing and echoing the city's essence. Most impactful was when Bowie began the tune for his song, Heroes. The song, which had been a result of Bowie’s take on a famous story about two lovers who crossed the Berlin Wall to meet. According to co-producer and friend Tony Visconti, Bowie drew inspiration for the lyrics after seeing Visconti and backup singer Antonia Maass share a kiss in the shadow of the Berlin Wall. The lyrics tell the story of two lovers and their dilemma caused by the Berlin Wall separating them. The song's authenticity, the emotions invested in it, and the lyrics that conveyed such power enabled Bowie to transcend the parameters of a rock concert. The song, recorded in a former concert hall that had been used by Gestapo officers during World War II as a ballroom and converted into a recording studio after the war, presented the reality that German youth faced. The lyrics, “Though nothing will keep us together, we could steal time, just for one day,” echoed not only across the side of West Berlin but also from the East.

Voices from both sides chorused across the area, with David Bowie’s music providing the backdrop for a cultural phenomenon that the GDR could not contain. The Wall was no longer there for those present, a surreal moment in time. David Bowie had later reflected on the power he felt resonating, “It was one of the most emotional performances I’ve ever done. I was in tears. God, even now I get choked up. It was breaking my heart. I’d never done anything like that in my life, and I guess I never will again.” While the concert brought a sense of togetherness for Berliners, it also sparked widespread outrage among the GDR authorities.

The Other Side

As the West Berlin organizers planned the concert, the GDR was concerned about its potential impact on its citizens. Considering it an act of ideological warfare by the “capitalist” FRG, the SED believed that since it could not stop the sound from reaching the citizens, they could move the people to a point where the sound could not get to them. They would have to devise a means of suppressing the congregation in areas near the Wall. This set the stage for a momentous historical event, a confrontation between the soft power of cultural attraction and the hard power of state coercion. It was a regime, grasping onto a fading past, against its youth who yearned for culture and connection beyond the Wall.

The crowd that gathered near the Soviet Embassy on the Eastern side of the Wall posed a security risk to the GDR. Thousands of people had begun to congregate, underscoring the youth's disillusionment with the regime. Before the concert had even started, the Volkspolizei, the national police force of East Germany, had begun dispersing groups of people gathering and chasing others with truncheons. It was at this time that the youth, as well as other participating citizens, began to chant, “Die Mauer muss weg!” which translated to “The Wall Must Go.” This was a monumental shift, signaling the desire for change. Emboldened by the sheer number of participants, these chants struck at the core of the GDR’s legitimacy. The East Berlin authorities did not take kindly to such a display of defiance, erecting barriers along the areas and making mass arrests. West Berliners would hear shrill cries from the other side, and during the concert, they saw objects such as rocks and cans being thrown over the Wall. This was merely the first day of the concert, and there were still two nights of performances following David Bowie’s show.

While the music served as a medium for highlighting people’s discontent, the movement that arose from it was purely political. Anger towards the state for arresting and taking away youth on account of simply enjoying music that the state did not approve of skyrocketed. Such a display not only exposed the cracks within the regime but also radicalized a generation, one that was beginning to understand the value of mass assembly.

The Dilemma

The bands Eurythmics and Genesis would go on to perform on the days following Bowie’s performance. The first day’s accurate metric for success was not the massive crowd that had gathered in front of the stage the first night, but rather the chaos that had erupted on the other side. By creating such instability and provoking an uprising through soft power, the West precipitated a crisis in the GDR. Their usual methods of brutal suppression through force were ineffective in the face of soft power such as music and caused panic within the SED. Such a loss of control over youth signaled a turning point, and anti-government chanting further underscored it.

This posed a significant dilemma for the SED, as its response would ultimately determine the course of events. Further suppression through violence could turn public sentiment even further, whereas allowing such gatherings in a sensitive region of Berlin could be seen as weakness and total loss of control. The crackdown on the first night, where youth were beaten and arrested on the charge of enjoying music, had sparked ordinary citizens to become political dissidents. A significant public image crisis: accounts of what had occurred were spreading rapidly among citizens.

While Western Media did its share of promoting the events of brutality that took place, the people themselves were spreading it through word of mouth. Already starting to get disillusioned with the state, this brutality took away the legitimacy that the SED had held as the “Protector” of the people. Once a cultural grievance in which youth desired access to music from over the Wall, it had become a political issue.

The Concert for Nicaragua

In a desperate attempt to appease discontent amongst the youth, the GDR organized its own concert. To please Western rock-music-loving youth, the decision was made to invite Bruce Springsteen to a concert in 1988, a year after the Concert for Berlin. Framed as the Concert for Nicaragua, the GDR attempted to highlight Bruce Springsteen as a champion of the working class, fighting against the imperial forces, forcing a connection between Springsteen and the socialist movement. This framing was not approved by Springsteen or his team either, blindsiding them when announced.

To convey soft power and display cultural capital, authenticity is essential. The public did not well receive this forceful co-option of Springsteen into the state’s ideology, and the concerts held on the other side, with their authentic identity, only heightened discontent. The Springsteen concert came after the 1988 Pink Floyd and Michael Jackson concerts in West Berlin, which had further exacerbated public defiance toward the regime. Pink Floyd’s performance of the song The Wall did not help matters either, as people hearing the music from the other side only desired change even more.

Going into the Springsteen concert, public sentiment was at a tipping point: people wanted culture and information, but the state still sought to demonstrate its control. The politicization of this show only alienated the youth. This was a display of the disconnect between the state propaganda and the true feelings of the people.

Springsteen in the East

The Bruce Springsteen concert in East Berlin in 1988 was a momentous occasion for the city. Most of the youth had never had the opportunity to attend a concert by a Western artist, far less one so well known. More than 160,000 tickets were sold, but reports indicate that nearly 300,000 people attended and breached the barriers to enter the concert. Controlling a crowd of such scale proved difficult for the Stasi, and as Springsteen took to the stage, the energy was palpable.

Recognizing the situation at hand, Springsteen seized the opportunity to address the crowd in German. He said, “I am not for or against a government. I’ve come to play rock and roll for you, in the hope that one day all barriers will be torn down.” This was a direct defiance of the East German authorities and was met with resounding approval from the crowd. The concert, which was broadcast across the GDR, had this section censored, but this did not stop word of the speech spreading. His decision to play the song "Chimes of Freedom" further resonated with the crowd, only heightening hopes that one day the Wall would come down.

This concert created a temporary space in Berlin where the regime’s authority did not apply. Springsteen became a platform for public discontent, and the performance highlighted anti-Wall sentiments. When people were able to come together in large numbers, it ignited a flame within them. It has even been suggested that this congregation was a precursor to the mass protests that broke out the following year. Through culture, people were able to come together and find a voice for themselves. The music did not bring in change, but it gave direction to the people.

Soft Power vs. Hard Power

The Concert for Berlin, as well as the events that followed, is a showcase of soft power and cultural capital confronting hard power and brutal suppression. Soft power is the ability to persuade groups of people through culture or other attractive means. In contrast to the traditional display of power through might, soft power focuses on drawing people’s attention through means that may also positively influence the image. Acts of soft power tend to make those who employ them appear in a much more positive light. The Berlin Wall was a physical manifestation of hard power, imposing its will through sheer physical presence. The SED had run East Germany through coercion and control, and the Berlin Wall signified such state authority.

Hard power is exercised through state authority; undermining such authority would render the state illegitimate. The Concert for Berlin, a showcase of soft power, aimed to do so. While the Eastern regime would require citizen participation through force and coercion, Western organizers persuaded youth in East Berlin with relative ease. By highlighting the culture and lifestyle, the concert organizers drew a massive crowd on the other side of the wall. Bowie was the highlight, whose music expressed artistic individuality and sexual fluidity, as well as themes of alienation, in sharp contrast to the state’s imposed ideals of rigidity and national unity. For youth to turn to an artist so far from state-sanctioned culture highlighted the losing grip of the GDR authorities over their people.

West Berlin organizers were aware that attraction can always overpower coercion. By offering youth the opportunity to experience such enormous cultural capital, they knew that people would congregate to listen. The West was well aware that it did not have to resort to spreading propaganda; it simply needed to showcase what the GDR regime could not offer. Something as simple as broadcasting David Bowie's Heroes could highlight the cultural attraction the West delivered. While the East Berlin authorities could underline the city's medieval core, they could not capture the minds of the youth. The expressive freedom that they could see from the other side had captured their hearts. People risked being arrested and assaulted to come and listen to the culture the West offered. That congregation was a display of how, against the coercive ideals of hard power, people would still be attracted to the attractive ideals of soft power.

Cultural Diplomacy

Soft power is adequate only when it is conveyed through authenticity and appropriately connects with the intended audience. If presented as merely information sharing, soft power will have little practical effect. It is critical to promote soft power through cultural diplomacy in ways that are more closely aligned with long-term relationship-building with an audience. Propaganda and force will repel audiences, but through a connection perceived as authentic, audiences can be persuaded.

The decision to have Bowie headline the concert proved to be the right one. Bowie carried that authenticity that audiences could turn to; he had lived in Berlin for a few years. He had embraced the city’s culture, and his music was a testament to that. To the people, he was not a tourist; he was an honorary Berliner. A visiting politician would not carry the level of credibility that Bowie had. When Bowie addressed the East Berliners, it was authentic. He was someone who understood the essence of the city; he had frequented local bars, he recorded music from a studio which overlooked the Wall, and he had participated in the city’s isolation, the bleak atmosphere that veiled over the people. Coming from Bowie, it was not some foreign musician trying to connect; it was a neighbor reaching out.

Bowie’s referral to those on the Eastern side of the Wall as “friends” left an impact as well. This was someone who understood the difficulties that this division had brought; he was a friend expressing his care. Through a cultural icon not associated with the state, West Germany was able to connect with East German youth. While the GDR regime could discredit state-sponsored propaganda or politicians from other countries, that same power did not apply to David Bowie. His connection to the people was not political; it was on a more personal level, almost. This concert demonstrated how effective cultural diplomacy can be when approached with authenticity and conveyed by an actor with whom the audience can connect deeply. A genuine human connection is always more effective in these contexts than direct instruction or coercion.

Sound Diplomacy

This concert is also a case of Sound Diplomacy being utilized with utmost effectiveness. Music has long been able to circumvent government restrictions and forge deep emotional connections with people worldwide. In many cases, it has been observed that even when certain kinds of music were outlawed in a given area, people would find ways to listen to it. This concert proved that, even at the risk of being beaten and arrested, people gathered around the Wall just to experience David Bowie live.

Concert for Berlin was a carefully orchestrated act of sound diplomacy intended to showcase growing discontentment within East Berlin. Deliberately directing speakers to face the Wall and announcing concert times via RIAS were planned efforts to take over the auditory spaces of East Berlin. Even in congregations, authorities could detain attendees, but there was no way to stop the music. The idea could not be suppressed, the message could not be silenced. This act of sound diplomacy, breaking the illusion of the state’s domination, effectively served as a psychological turning point for the people. Not only was it a display of the state's loss of control, but it was also an experience that transcended borders. Through such a shared connection, the Berlin Wall nearly disappeared, and people were united in this cultural experience. This auditory unification, coupled with Bowie's song about how the couple can remain together despite the wall between them, prompted listeners to yearn for an end to this separation.

The Power of Cultural Diplomacy

The Concert for Berlin is a case of successful cultural diplomacy and the spread of soft power. By mobilizing cultural capital, the West elicited a highly politicized response in the East, thereby delegitimizing the GDR authorities. While it would be incorrect to say that David Bowie brought down the Berlin Wall, he was among the critical catalysts that ultimately led to the mass protests that brought it down. The concert transformed silent discontent into a call for political action. Through such an act of cultural diplomacy, the GDR’s loosening grip over its people had been exposed. Such a display of its cracks had backed the GDR into a corner, leading to strategic errors in the years that followed, and within two years of the concert, the Wall came down.

One of the primary lessons from the Concert for Berlin is the use of public diplomacy to overcome physical barriers. Through the use of sounds, the organizers and RIAS were able to overcome the wall and undermine the GDR. Effective public diplomacy requires careful coordination and planning to achieve its intended goals. Public diplomacy is most effective when undertaken through strategies that exploit the opposition’s weaknesses. In this case, by playing the sound through speakers facing the wall, organizers were able to permeate the physical barrier and spread the sound into East Berlin. The concert also demonstrated the importance of authenticity in public diplomacy. What made the concert so effective was that it resonated deeply with the youth of East Berlin. By accounting for the youth’s desire for Western culture and introducing a Berlin icon, the West was able to connect with an Eastern audience. Messaging grounded in authenticity and appeals to a genuine human connection holds greater value for audiences than manufactured messaging or propaganda. Cultural figures with ties to the audience may at times carry greater credibility than official government communication.

This concert was a significant turning point for East Berlin's youth, whose desire for culture had transformed into a desire for political change. Although it did not immediately alter the structure of the GDR, it was among the earliest instances of mass chanting of anti-regime slogans in East Germany. Through David Bowie, West German organizers persuaded people toward such a change. This destabilization, which undermined the state’s control over the people, played a critical role in the eventual fall of the Wall. When David Bowie passed away in 2016, the German Foreign Office posted on Twitter, “Good-bye, David Bowie. You are now among #Heroes. Thank you for helping to bring down the #wall.” This concert has etched itself in history as not just a showcase of culture but a time of unification, when human connection overcame brute force and coercion.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.