Cinema Diplomacy is Alive and Well…For the Time Being

The film industry like the Ottoman Empire of yore seems to be in perpetual crisis. Trade organizations – the most notable being the U.S. film industry’s MPAA – regularly deliver dire warnings about the damage wrought by DVD piracy and competition from the improvements in home viewing technology. Then there are the doomsayers who note that video gaming has long since overtaken motion pictures as a revenue generator. Yet if nation states and other practitioners of public diplomacy are anything to go by, then cinema is still seen as a central vehicle for international communication. This past month has seen a number of stories confirming the supremacy of celluloid from Ban Ki-moon’s mission to Hollywood to promote better coverage of UN issues, to the continued initiative by the Australian government to promote the country through film; from the tussle over the extent to which Arab-Israeli director Scandar Copti represents Israel, or the remarkable ability of Bollywood to bridge the divide between India and Pakistan as evidenced in the recent success of My Name is Khan. In the midst of it all the Academy Awards provided their annual showcase for the medium that still captures the collective imagination as no other.

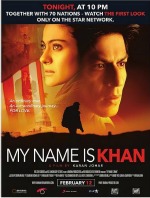

My Name is Khan, Creative Commons, © Flickr 2009

The interest of public diplomats in cinema is no surprise. Cinema diplomacy has a long history and America has led the way. In the First, Second and Cold Wars, the U.S. government worked closely with producers to get the message it needed to world audiences and turn a profit in the process. Contemporary advocates of better U.S. public diplomacy are quick to point to the enduring power of film and the need for Hollywood to maximize its ‘soft power’ potential for the greater good of the country (usually by dropping violence and crime as themes). Reading between the lines of this month’s PDiN articles, it seems that talk of changing or amplifying America’s voice may actually be missing the point. The best public diplomacy flows from listening and films offer an important mechanism to enable Americans and others to see this world through someone else’s eyes. Americans interested in listening would do well to watch My Name is Khan. The film is an amazing example of the world thinking aloud about the experience of America. It includes scenes that should alarm Americans – an Indian boy beaten to death in a U.S. high school, the devastation wrought by a hurricane in the deep South and the autistic Muslim protagonist tortured in U.S. custody – but it also reflects the hope embodied by America with the immigrants coming to the U.S. in the first place and a final reconciliation between the protagonist – Khan – and the country in the person of its enlightened new president Barack Obama. For better or worse, America is a character in the world’s dreams and hence has both a lot to live down and to live up to.

Then there is the matter of Avatar. Although it was snubbed by the Academy, Avatar is a colossus which now bestrides the world. Its 3D format has given the movie industry a product which for the time being cannot be matched on TV, and one for which the cinema owner may charge extra. As The Jazz Singer dragged the film industry of 1927 into the sound era, so Avatar has begun a stampede into 3D. It offers a powerful example to public diplomats also. The full force of Avatar’s overwhelming visual experience is harnessed to an intensely political story: a plea for indigenous rights; an indictment of big business, military contractors and the logic of ‘shock and awe’ and some pleas for diplomacy and cultural understanding that were music to the ears of public diplomacy scholars. In some ways the film depicts a cultural exchange experience – Fulbright in space. The environmental message comes through most strongly. Could Avatar do for the transnational environmental movement what Uncle Tom’s Cabin did for anti-slavery? The director James Cameron certainly hopes so. But what does Avatar say about America? Does the film speak for a national culture? Perhaps, but not the culture the world assumes. Cameron has been called many things these past months. Perfectionist – genius – obsessive – visionary. One word missing from most discussions is: Canadian. Cameron was born in Ontario and moved to California as a teenager, but his sensibilities – anti-militarism, mistrust of technology (on-screen at least), reverence for native cultures and even his foregrounding of strong female characters – reflect the world above the 49th parallel. Is his story an example of the ability of America to assimilate all-comers? Certainly. Does his enduring Canadian-ness present further evidence of Hollywood as an essentially transnational epicenter of storytelling in which the United States is sometimes merely the geographical space in which global ideas and talents converge? I think so. Whatever the case, the world is watching.

Tags

Issue Contents

Most Read CPD Blogs

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

January 2

-

February 6

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

Add comment