Globalization, Interdependency and Public Diplomacy

It is by now well-known that the process of globalization, beginning in the 1960s and picking up pace rapidly in the late 20th century, quickly changed the context for international affairs. Globalization produced increased contact among the peoples of the world, a rapid expansion of interdependence among nations, and an explosion of new actors in international affairs. At the heart of this globalization process were the sovereign decisions of countries to open their borders to the flow of goods, capital, ideas, and people, and the technological changes that enabled a rapid increase in these cross-border flows. Beyond the evident advances in transportation technologies, it was (and still is) the revolution in communications technology that has defined this latest and most profound phase of global integration.

The consequent “shrinking” or “flattening” of the world, in addition to the associated growth of new international power centers such as China and India, has profoundly influenced the con-duct of foreign policy. Issues such as trade, finance, migration, human rights, and environmental concerns – issues that resist resolution through the traditional application of hard power – have begun to matter more in global affairs. The resulting interdependencies among nations have swelled the domestic costs of attempting to coerce others to alter their behavior.

“China’s decision to play the role of an international ‘free-rider’ rather than a rising world leader tarnished its global image”

As a result, the need to build cooperation, to persuade and cajole, to build shared codes of conduct from which all actors might benefit, has grown in importance for diplomats of all stripes. This clearly does not mean that hard power has ceased to matter in the conduct of international affairs. It does mean that in the 21st century the diplomatic power to persuade matters more than ever before. Whether public or private, undertaken by nation-states or non-state actors, among actors with similar or unequal resource endowments, 21st century diplomacy must make conscious and creative use of soft power tools. Nations must therefore rethink which combination of policy tools is best suited to achieve their foreign aims.

News stories from throughout the world focusing on issues related to public diplomacy during the first weeks of 2010 reflect this revised thinking about the conduct of international affairs. These stories offer a peek into how countries are trying to adapt their foreign policy to a changed, and still changing, global context and how soft power and public diplomacy resources might be used to better effect. The stories also reflect an uncertainty as to what this really means in the practical application of policy.

Some examples of this include the Daily Star article examining how the Bangladeshi government ought to rethink its relations with India given the growing importance of economic issues; the Channel NewsAsia article reporting on efforts by the Indian government to better exploit the economic power of its diaspora in Singapore; the Financial Times article discussing the implications of the positive interdependencies that could be created from the construction of a proposed natural gas pipeline from Turkmenistan through Afghanistan to Pakistan; and the Thanh Nien News article reporting on Joseph Nye‘s visit to Vietnam where the most influential foreign policy analyst of interdependence and soft power encouraged the Vietnamese government to take advantage of holding the ASEAN presidency to the country‘s soft power.

Yet the dominant story line among these articles is, unsurprisingly, China. The Economist article, “From the Charm to the Offensive,” presents some background to the story noting the Chinese government‘s late 20th century determination not to rely on military force to fuel its global rise. This decision reflected the undisputed military dominance of the United States at the time, but it also reflected an international context increasingly defined by globalization, interdependence, and the opportunities this afforded China. China consciously relied on cooperative rather than coercive tactics to enable its rise, including bilateral negotiations to gain access to raw materials, multilateral negotiations to resolve (or ease tensions surrounding) a series of border disputes and to reach regional trade agreements. This has been coupled with the use of international Expos and participation in international forums to signal China‘s arrival as a global player and with the use of economic assistance and cultural institutes to soften international fears of China‘s growing economic might.

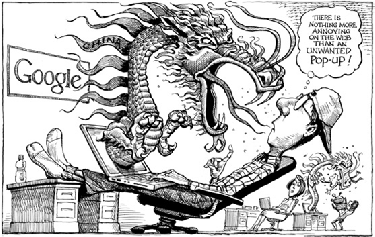

Despite these concerted foreign policy efforts to manage China‘s “soft rise.” at the beginning of the second decade of the 21st century increasing conflict appears to be in China‘s foreign policy future. Indeed, international spats have already begun to erode China‘s image in the West as The Economist article on Chinese-EU relations demonstrates. The greatest challenge potentially to China‘s ability to manage its global image, however, just hit the headlines – how China will manage the growing dispute with Google and the U.S. government over information espionage and internet access.

Kevin KAL Kallaugher

© kaltoons.com

This rocky patch for China‘s international image seems almost inevitable in hindsight. China‘s foreign policy exhibits three characteristics typical of emerging powers – its expanding power makes it crave respect as a significant international actor, yet domestic objectives continue to define its foreign policy and its recent history of weakness makes it highly sensitive to perceived international slights. China‘s performance at the Copenhagen climate change summit is instructive. Necessarily included in the core group of nations negotiating a final accord, China was willing to make only very limited domestic sacrifices to achieve a common international goal. China‘s decision to play the role of an international “free-rider” rather than a rising world leader tarnished its global image. Nothing is unique about this decision; the United States behaved similarly during its rise to global power in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But it means that China will have to rethink how it employs public diplomacy to mitigate the inevitable tensions with the West that its “emerging” status is likely to produce. While the Global Times interview with the Chinese foreign minister shows that China is aware of this challenge, effectively modifying its use of soft power and public diplomacy to contain global concerns about an increasingly powerful China will not be easy.

This will be particularly true in the run-up to the 2012 change in Chinese leadership. In this time period, the primacy of domestic economic development will dovetail with an overarching need for international and domestic stability to help political leaders in Beijing manage this transition. This situation is likely to enhance China‘s deep-rooted sensitivity to Western criticism of its commercial and exchange rate policies and lack of domestic political freedoms.

Within this policy context, China faces one of its greatest public diplomacy challenges –managing the backlash from its commercial dispute with Google and the policy response it has generated from the United States. Secretary of State Clinton took advantage of this dispute to incorporate internet freedom as a new plank of 21st century American foreign policy, which The Wall Street Journal immediately dubbed the “Clinton Doctrine.” In her January 21 speech, Secretary Clinton argued that “those who disrupt the free flow of information in our society or any other, pose a threat to our economy, our government and our civil society” and she referred specifically to China as one of the countries in which “a new information curtain” had descended. The fight against internet censorship, she argued, “needs to be part of our national brand.”

The Chinese reaction was immediate and strident. Edward Wong‘s article in The New York Times reports on “a scathing editorial in the English-language edition of The Global Times, a populist, patriotic newspaper” which described the Clinton Doctrine as a form of “information imperialism” and an attempt by the United States to use the Internet as a weapon to sustain its international hegemony. This reaction is hardly surprising, and not merely because of the Chinese sensitivities to criticism of its domestic affairs noted previously.

It also reflects the unique challenge posed by the Internet for an authoritarian emerging market like China which the Clinton Doctrine explicitly aims to exploit. Throughout most of the 20th century, U.S. public diplomacy relied on broadcast media to promote the ideas of freedom, human rights and democracy. This strategy suffered a core weakness, however: There was almost no downside for governments choosing to block these signals. The internet is different. It is an indispensable tool of development as well as the medium through which ideas at odds with authoritarian rule now traverse sovereign borders. Because of the costs for economic development this would entail China cannot simply block the Internet like the Eastern Bloc and modern-day Cuba have done with radio and TV signals. Until now the Chinese government has allowed selective use of the internet among its citizens, trying to allow in “good” ideas while blocking “bad” ones. The Google dispute and the Clinton Doctrine pose a real threat to this strategy.

How China will adapt remains unclear. Its dilemma, however, presents a striking example of how increased interdependence and new communications technologies are changing the nature of international affairs and particularly the conduct of public diplomacy in the early 21st century.

Issue Contents

Most Read CPD Blogs

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

January 2

-

January 8

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

Add comment