middle east

In 2010, I returned to London to meet again with the nation-branding consultants I had interviewed three years earlier. I expected to encounter a very different portrait of the field from the one that had been painted for me a few years earlier. Aftershocks from the global financial crisis of 2008 – 2009 continued to make themselves felt, upending the foundations of market value.

The deteriorating security situation throughout much of the Arab world underscores the need to urgently search for nonviolent methods of achieving stability. At the heart of the current unrest are not only political issues but also economic failures that are wiping out the vestiges of hope that remain after the region’s recent revolutions. In conflict situations, public diplomacy must be employed carefully. Sometimes the swirl of violence becomes so pervasive that it sucks up the oxygen needed for peaceful enterprise to survive.

The deteriorating security situation throughout much of the Arab world underscores the need to urgently search for nonviolent methods of achieving stability. At the heart of the current unrest are not only political issues but also economic failures that are wiping out the vestiges of hope that remain after the region’s recent revolutions.

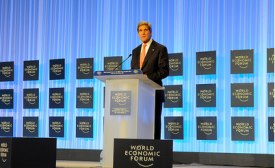

US Secretary of State John Kerry has arrived on an unannounced visit to Egypt as he begins a tour of countries in the region. Mr Kerry, the most senior American official to visit Egypt since the ousting of President Mohammed Morsi in July, will stay only a few hours. The visit comes at a time of tension between Washington and Cairo. Mr Morsi is due to go on trial on Monday.

A KFC franchise sits on Cairo's iconic Tahrir Square, the site of nearly three years of demonstrations that have helped unseat two Egyptian presidents. But in a country rife with conspiracy theories, the Colonel hasn't been able to keep away from controversy during the constant protests. In early 2011, as demonstrators called for then-Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak's resignation, rumors trying to paint them as Western puppets said they were being compensated for their fervor with KFC meals. The Los Angeles Times has the lowdown.

Iran’s new president, Hassan Rouhani, told world leaders Tuesday that his government is prepared to “engage immediately in result-oriented” talks with the United States, but also complained about American economic sanctions and military intervention in the Middle East. In a widely anticipated speech at the United Nations General Assembly, Rouhani said that Iran and the U.S. “can arrive at a framework to manage our differences,” adding that his government has no desire to increase tensions between the two longtime adversaries.

As the United States debates its role in the ongoing turmoil in Syria, we might do well to remember our initial foray into the region nearly a century ago. The very first American intelligence officer dispatched to that region was a 29 year-old man named William Yale. Until the United States entered World War I in April 1917, he had been living in Ottoman-controlled Syria as a local agent for the Standard Oil Company of New York.

It started as “a new beginning” and ended as “America is not the world’s policeman.” Between President Barack Obama’s historic 2009 address to the Islamic world in Cairo to his address to the American people on Syria last week, Obama has zigged and zagged on Mideast policy, angering supporters and detractors alike. But he has stuck to a clear pattern: reduce American engagement, defer to regional players and rely on covert operations to counter terrorism.