James T. McHugh, a political science professor at the University of Akron in Ohio, has published a new article. His piece, "Paradiplomacy, Protodiplomacy and the Foreign Policy Aspirations of Quebec and Other Canadian...

KEEP READINGThumbnail Image:

Can Public Diplomacy Help Bridge the Gap Between Reality and Perceptions?

The relationship between the United States and Mexico is a vital one for both countries. Increasing win-win interdependence and cooperation between the two governments has been one of the beneficial results of NAFTA since its inception, negotiation, approval, and entry into force in the early 1990s. This North American partnership is facing serious challenges, however, not the least of which is foundering public perceptions of the other nation on both sides of the border. One of the keys to surmounting this particular challenge lies in improved public and cultural diplomacy efforts, in which the strategic use of social media and digital diplomacy can play a critical role. In many ways, the opportunities and challenges of the relationship seem Dickensian, if one compares the positive synergies triggered by both governments in recent years and the generally negative public opinion perceptions of one another on each side of the border as to state of affairs of the bilateral relationship. This dichotomy between the gains and traction achieved in diplomatic relations and where public opinions stand today would suggest that it is the “best of times” and the “worst of times”!

A New, Forward-Leaning, and Strategic Relationship

NAFTA became the midwife of a profound transformation in the diplomatic ties between Mexico and the United States. Aiming for a paradigm shift in its prickly and distant relationship with the U.S., Mexico, which had traditionally had a jingoistic, inward-looking, protective, Westphalian-based outlook on foreign policy and international affairs, was forced to develop a more open, accountable, and modern world vision in the aftermath of the end of the Cold War. The dynamics of lining up votes on Capitol Hill to approve NAFTA meant convincing a very heterogeneous group of members of Congress to support the agreement, which also forced Mexico to establish a new way of doing business with a multiplicity of U.S. actors. Everything from sugar to extraditions to steel quotas had to be discussed and examined, and this forced Mexico to abandon the protective foreign policy that it had articulated throughout the 20th century, and to change the underlying dynamics and touchstones of its engagement with the United States.

Since then, NAFTA has changed the way both governments interact with one another, in part because it has been so successful. Granted, not everyone would define it as a success, but we must remember that NAFTA is and was one thing and one thing only: a free trade agreement meant to foster trade flows in North America. It is not an extreme poverty alleviation tool. Nor is it meant to promote sustainable development. It was designed to boost and trigger bilateral trade between Mexico, the United States, and Canada. And that it has done, and done so formidably well.

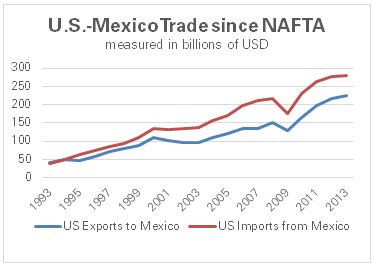

Source: U.S. Dept. of Commerce

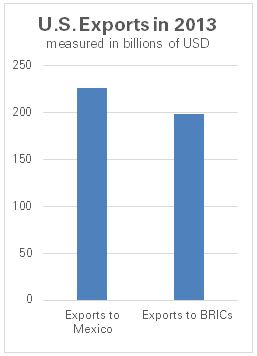

Few people realize that Mexico and the United States trade $1.4 billion dollars a day of goods across our common border. This is a stunning figure. Since NAFTA was negotiated in 1993, trade between Mexico and the United States has quadrupled. Mexico has become the U.S.’ third-largest trading partner and is the second-largest buyer of U.S. exports. To put this into context, Mexico buys more U.S. goods than all of the nations of Latin America and the Caribbean together; buys more U.S. exports than the U.K., France, Germany, and Italy put together; purchases more than the joint imports of U.S. products by Japan and China; and more than the four so-called BRIC nations combined.

Source: U.S. Dept. of Commerce

This is a very compelling success story about trade—after all, that’s what NAFTA was seeking to transform. As a result of this success and the Mexican government’s decision to use free trade agreements to create growth via exports, Mexico is now the country with the largest free trade agreement network on earth, second only to Chile. This has led to an economic boom in terms of manufacturing capabilities, and increasingly, in high value-added exports from Mexico.

Today, the two most dynamic new-growth sectors in Mexico are aerospace and I.T. Querétaro, the central part of Mexico, is the fastest-growing aerospace hub in the world. There are I.T. hubs in Guadalajara and Mexicali.

Canadian, U.S., and European companies each have established footprints in these regions and are taking advantage of the unique education “hatchery” system that has been developed in engineering in Mexico, which ties community colleges and their curricula to the labor and business footprints of the region. This ensures that local community college students will almost certainly have a job when they graduate, because they have been trained by and for the aerospace or I.T. sectors. More engineers are graduating in Mexico today than in the U.S.

This has had not only a profound impact on the Mexican economy, but will also affect the U.S.-Mexico relationship regarding an issue that has been a pernicious and constant challenge: immigration. For the past two years, migration from Mexico to the United States has reached net zero. One could argue that this is the result of a soft U.S. economy since 2009, particularly in the construction industry (one of the magnets for undocumented labor in the U.S.). One might also claim that increasing violence, transnational organized crime, and human trafficking along the border has made migrants more hesitant to cross. But these arguments overlook important factors that might give potential migrants incentives to remain in, or return to, Mexico.

The export-driven growth that has been triggered by NAFTA and Mexico’s decision to pursue free trade agreements as a means for economic growth is of paramount importance. A second factor is that since Mexico triggered a potentially devastating global financial crisis in 1994 (when the country almost defaulted and dragged all the emerging economies down with it, and the U.S. government put together a financial rescue package that allowed Mexico to stave off a very profound crisis), Mexico has put its economic house in order. Sustained, sound, and responsible macroeconomic policies have been implemented since then, regardless of which political party was in power. These regulations explain, among other things, why even after the 2009 recession, Mexico grew for 13 consecutive quarters, with an average rates of 3.1% inflation and 4% unemployment at 3.1% and 4% respectively. The third factor that has impacted immigration patterns is changing demographics. Mexico is becoming an older country, with decreasing birth rates. Last but not least is Mexico’s sustained and continued implementation since the early 90s of what is probably the most successful extreme poverty alleviation program: conditional cash transfers, targeting the female head of household and predicated on benchmarks that must be met. This program has brought 40 million people out of extreme poverty in Mexico since it was inaugurated, and has become a template for similar programs in Brazil and Peru. It’s the combination of these four factors that is profoundly impacting flows across the U.S.-Mexico land border.

In addition, both countries are starting to understand that if they are to maintain these 1.4 billion dollars a day of trade, they must completely revamp their borders. Since 9/11, there has been an emphasis on ratcheting up border security. For a country like Mexico, with a 3000 km land border with the United States, the perception of threat or an actual threat materializing on the Mexican side would have had—and could still have— profound implications for the relationship that it has been building with the United States since 1993. Therefore, it behooves Mexico to work together with the U.S. to ensure that no potential terrorist or terrorist organizations undermine U.S. security across the U.S.-Mexico border. The template developed since 2001 has allowed Mexico and the U.S. to dramatically enhance and improve intelligence-sharing and security and law-enforcement cooperation in the fight against transnational criminal organizations. The challenges, however, have been to harmonize the need for common security with the need for common prosperity, and to develop a risk-driven and risk assessment approach, much like a membrane that allows the good stuff to go through, but not the bad stuff, rather than an impermeable wall.

The test—and opportunity—will be in developing a 21st century intelligence- and technology-driven border, with modern infrastructure. If NAFTA is to continue to be an economic and trade success story, it will have to deal with the fact that whereas our trade flows and joint production platforms are 21st century, our legal framework— NAFTA itself—is from the 20th century, and our border infrastructure is from the 19th century. Mexico and the U.S. have not built a new railroad crossing the border since the days of the Mexican Revolution in 1910!

But new paradigms and policy breakthroughs are being devised and implemented every day, from water on the border to global affairs. For example, a new holistic water management framework was negotiated in 2008, and implemented through a bilateral agreement in 2012 (Act 319) on the Colorado River Basin, an historically sensitive and politically fraught issue. Unthinkable a decade ago, the agreement has allowed Mexico and the United States to jointly manage the area’s scarce water resources and repair the damaged and delicate ecosystems of the river’s delta, with the co-stakeholdership of Federal, state, and local authorities and of NGO’s. On global issues, which traditionally had not been part of the bilateral diplomatic agenda between Mexico and the U.S., greater coordination, engagement, and synergy in areas of common concern have blossomed in recent years, whether on nuclear proliferation, global economic governance in the G20, or environmental sustainability.

And as a backdrop to all of this, we have witnessed the growing political, economic, social, and cultural empowerment of the Latino community in the United States. This presents a huge opportunity for Latinos to play a greater role in how the United States engages with its partners to the south. In recent years, we have already seen that civil society leaders are starting to rethink how to engage U.S.-Mexico bilateral relationships. Southern California and Northern Mexico are increasingly becoming cultural spark plugs. There is a unique cultural dynamism in this transborder region that is changing cultural paradigms in both countries, and this is a huge asset for two global cultural and creative industries powerhouses like Mexico and the United States.

An Albatross of Public Perceptions Around the Relationship’s Neck

Why then, if the muscle tone of the relationship is as good as it is, do we face a disconnect in what publics in both countries say and perceive about the U.S.-Mexico relationship? Public perceptions in each nation regarding the other are driven by several factors.The first is immigration, which presents the unique challenge of two societies looking at the same issue through two very different lenses. For most Mexicans, when considering Mexican migration to the U.S., the main concern is fairness. Are these individuals who are contributing to the economic vitality and well-being of the United States being treated fairly? For most Americans, on the other hand, the concern is for the rule of law. Have these individuals broken the law, crossing the border illegally without papers? As long as these two disparate sets of values live side-by-side on either side of the border—in the press and in public opinion at large—creating different narratives about immigration reform within each society will continue to be vexing and will most likely remain unresolved. Because the United States failed to deliver immigration reform, especially after 2006 and 2007, and because of increasing efforts at the state and local levels to clamp down on immigration, perceptions of bilateral relations with the U.S. profoundly deteriorated in Mexico, despite the fact that both the Bush and Obama administrations have unsuccessfully used the presidential bully pulpit to push for reform. In the U.S., on the other hand, there is a perception that Mexico uses emigration as a safety valve to release pressure on unemployment inside its own borders, and that it cannot provide for its people, despite the aforementioned changes in flows across the border.

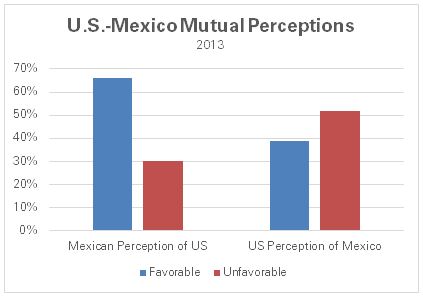

Source: Pew Global Attitudes Project

The second issue has been the violence triggered by the changing modus operandi of transnational criminal organizations over the last 10-15 years. This has been exacerbated by both countries’ mainstream media’s unfortunate adoption of tabloid practices, of simplifying and exaggerating, and of going with the “if it bleeds, it leads” dynamic. Through these practices, violence has become the main narrative about what was happening in Mexico over the past six years, and has led once again to a rather simplistic public understanding of what’s behind the surge in criminality, violence, and drug abuse. For a majority of Americans, “Mexico send the drugs” to the U.S. For a majority of Mexicans, the U.S. feeds the violence and insecurity by allowing guns and bulk cash to cross into Mexico, and by its consumption of illicit drugs.

The third issue that has not helped Mexicans’ perceptions of the U.S. has been the series of revelations about U.S. agencies’ intelligence-gathering capabilities and practices, first through WikiLeaks and more recently with the NSA-related information released to the media by Edward Snowden. Regardless of what this means for bilateral ties in concrete terms—and what motivations public opinion ascribes to those practices—or how the day-to-day diplomatic relationship is or isn’t impacted by these episodes, the truth is that perception, as always, becomes reality, and it has not helped in Mexico, nor with other global partners and allies of the U.S.

A Role for Public Diplomacy

Social media in general, and particularly digital diplomacy, have started to play an increasingly important role in relations between the U.S. and Mexico. Nowadays, government officials and diplomats have a new and unique—albeit still rather untested— tool for putting relevant information out into the public arena, and to try and engage public perceptions. The ability to articulate ideas via social media platforms, such as Twitter or Facebook, is very useful in trying to impact public perceptions on challenging issues, particularly in two nations with broad—and in the case of Mexico, growing— digital interconnection. Both our respective embassies in Washington and Mexico City, as well as most of our vast network of Consulates in either country,2 are using Twitter accounts to communicate, to listen, to correct narratives, and increasingly and gingerly, to engage, connect, and interact.

The richness of our human and social connections; the fact that each country has its largest diaspora/expat/migrant community living in the other; the economic and trade drivers that impact everything from investment, job creation, and business opportunities to lifestyles, values, and gastronomy; that for good, or occasionally for bad, so many of our challenges and opportunities are interconnected and have truly become “intermestic”3—rooted in the domestic politics, values, ideologies, constraints, and parochial interests within each nation but expressed in a complex international, cross-border dialogue between both nations—gives both governments, their foreign policy establishments, and their diplomatic corps an opportunity: to bridge some of the recurring misperceptions and lack of knowledge about the other via social media platforms, and to create a more ambitious, comprehensive, long-term, mutually reinforcing, and sustained design and implementation of public diplomacy.

Some Americans and some Mexicans may not enjoy reading this (or even agree) but there is one inescapable truth which has been developing since the early 90s, accelerating in the decade after NAFTA, and changing the face of the U.S.-Mexico relationship: Mexico and the U.S. are converging, as societies and as economies. Recent successes in the deepening and widening of our bilateral ties (notwithstanding the tyranny of past mistakes, failures, and lost opportunities), the promise of what the energy revolution in North America—and the hopes for energy reform in Mexico— could achieve for economic growth and energy independence; the potential of a middle-income Mexico solidifying over the next decade; growing societal, cultural, and transborder connectivity and synergies between communities; and the increasingly integrated production and supply chains adding economic and labor value, are all part of a vision of public diplomacy implemented by each nation to strengthen a mutually beneficial relationship, and a greater sense of co-stakeholdership on either side of the border. Properly designed and orchestrated, U.S.-Mexico public diplomacy efforts can help develop a template for strategic communications that so far has escaped both governments. And in terms of public perceptions, it can help convey the three most simple, but radically important and powerful, notions that both societies need to comprehend and assimilate: 1) a common rising tide will lift boats on both sides of our border, b) we can become partners in success instead of accomplices to failure; and c) both countries will either succeed or fail together.

1. This article is based on a lecture given at the USC Center on Public Diplomacy in November 2013.

2. In the U.S., Mexico has the largest number of career Consulates any one country has in another nation: 50. The U.S. has the largest number of Consulates any country has in Mexico.

3. Former Council on Foreign Relations president Bayles Manning coined the term “intermestic” in a 1977 Foreign Affairs article, in order to convey the changing nature of American foreign policy by underscoring how domestic politics was increasingly shaping and impacting international policy. I have liberally hijacked his term to portray the changing nature of the U.S.-Mexico relationship, the profound synergies between domestic political drivers in each country, and how they impact the day-to-day bilateral diplomatic relationship.

To download a PDF of this article, click here.

Author Biography

Arturo Sarukhan is an international strategic consultant and advisor. He is currently a Distinguished Fellow at the USC Center on Public Diplomacy. A career diplomat, Ambassador Sarukhan served for 20 years in the Mexican Foreign Service and most recently served as Mexican Ambassador to the United States from 2007 to 2013. Previous positions included Deputy Assistant Secretary for Inter-American Affairs, Chief of Policy Planning at the Foreign Ministry and Mexican Consul-General to New York City.

To read more about Ambassador Sarukhan's involvements with CPD click here.