Note from the CPD Blog Manager: This is part 1 of a photo essay series exploring Expo 2020 Dubai through historical context, individual country participation and public diplomacy opportunities through Expos. The author...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

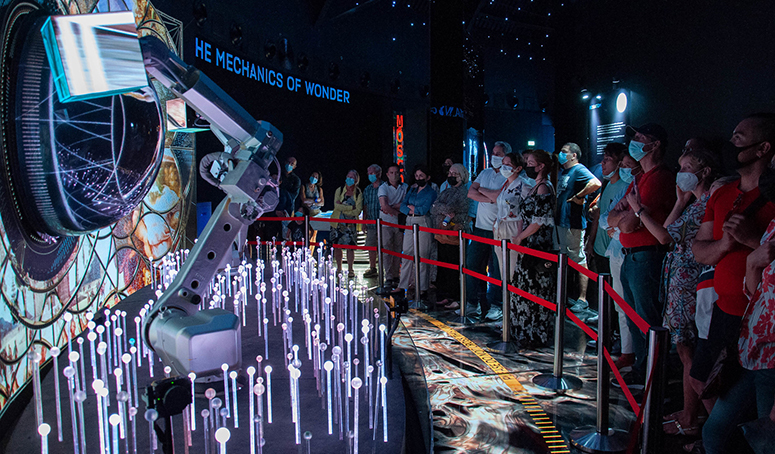

Expo 2020 Dubai: How Expos Became a Source of Inspiration for Innovation

Note from the CPD Blog Manager: This is part 2 of a photo essay series exploring Expo 2020 Dubai through historical context, individual country participation and public diplomacy opportunities through Expos. The author is CEO of ExpoMuseum.com. Read part 1 and part 3.

Historical references in this piece include: Les expositions internationales au XXe siècle et le Bureau International des Expositions by Marcel Galopin (L'Harmattan, 1997) and Fair world: A history of world’s fairs and Expositions, from London to Shanghai, 1851-2010 by Paul Greenhalgh (Winterbourne: Papadakis, 2011).

The path connecting the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations of London 1851 to Expo 2020 Dubai is complex and has demanded strong international collaboration.

Many authors wrongly portray Expos as direct descendants of trade fairs. Industry indeed is one of the motors behind the birth of Expos, and trade fairs and Expos bear some similarities. However, this approach fails to explain some essential characteristics of Expos:

- The main purpose of Expos is the education of the public.

- Expos are fundamentally non-commercial.

- Expos do not happen periodically in the same place.

- Official participants in Expos are governments of other countries—not businesses—invited exclusively through diplomatic channels.

In the U.S., the term primarily used for Expos is World Fairs, which can be misleading. Fairs (from the Latin feriae, meaning religious festivals) have historically been temporary trade sites located around religious festivals. Unlike Expos, fairs are fundamentally commercial and happen periodically in the same place.

Pavilion of Russia at Expo 2020 Dubai.

(César Corona / Expomuseum.)

The purpose of Expos is not commercial but educational. In the century before the Great Exhibition, France and the United Kingdom held national exhibitions to educate the middle classes and foster innovation.

In the aftermath of the French Revolution, France feared having to depend commercially on the British Empire. In 1797, France hosted a national exhibition that promoted national products and sent a message of self-confidence to French industry. In a second exhibition, selling was still a central objective, but French manufacturers were encouraged to work harder, consider the importance of their products’ presentation and introduce more aggressive marketing techniques. France organized eleven national exhibitions between 1797 and 1849.

The United Kingdom held similar events which, although smaller in scale, were more openly oriented toward education. The Society of Arts encouraged a positive impact of the arts on trade and industry. From 1760, it carried out exhibitions in which art was expected to have practical use. From 1837, the Mechanics Institutes followed the example of the Society of Arts and organized art and industry exhibitions in numerous cities around the United Kingdom. The purpose of these exhibitions was philanthropic, rather than economic, with the objective of stimulating the consciousness of the working class and promoting an industrial culture in general.

Pavilion of Portugal at Expo 2020 Dubai.

(César Corona / Expomuseum.)

France and the United Kingdom gave national exhibitions—which later became international—their educational character from two different perspectives. France needed to show techniques to its industry and give it the confidence to become stronger nationally and internationally. The United Kingdom was not engaged in selling but developing technology.

In 1834, Jacques Boucher de Perthes recommended that French national exhibitions become international, hoping domestic manufacturers could learn from foreign producers. In 1849, the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce of France presented the notion for the second time. However, both proposals received widespread disapproval because of generalized distrust of free trade’s effects on the French economy.

Henry Cole, the main organizer of the Exhibition of 1851 in the United Kingdom, heard the idea at the French exhibition in 1849 and presented it to Prince Albert, President of the Royal Commission for the Exposition of 1851. Prince Albert supported international participation, and Queen Victoria invited other countries to the Great Exhibition; 25 countries were represented at the first Expo.

Opening ceremony of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, London, 1851.

(Courtesy Expo 2020 Dubai.)

The popularity of Expos over the next 80 years originated several problems. Participating countries had difficulty differentiating between official and private exhibitions, with some organizers inviting foreign countries without their own government’s awareness; organizers abused customs regulations and favored monopolies; fake Expos sold prestigious awards to exhibitors; and diplomatic pressure on participating countries increased due to an uncontrollable number of Expos.

As early as 1867, during the Expo in Paris, Henry Cole, then-commissioner-general of the United Kingdom, wrote a memorandum to regulate the duration, size, classification, rotation and quality of Expos. The commissioners-general of Austria, Italy, Prussia, Russia and the U.S. supported the initiative, but it did not have any significant impact.

Several European countries continued to work with limited success toward regulation. Despite not having organized any Expo, in 1912 Germany brought together accredited representatives from 16 countries at a diplomatic conference. The Berlin Convention never entered into force, but it established several of the concepts and regulations used today.

In 1928, France convened a diplomatic conference that gathered 40 countries in Paris. The conference resulted in the Convention Relating to International Exhibitions, which entered into force on January 17, 1931. The Convention not only addressed the issues I mentioned above, but it also created the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE), an intergovernmental organization comprising 170 member countries. Three protocols and two amendments have modified the Convention of 1928, particularly regarding categories, size and frequency, which explains different patterns in denomination, site characteristics and dates.

The BIE’s General Assembly elects the host countries of Expos. Currently, five countries are bidding to host Expo 2027/2028 (Argentina, Serbia, Spain, Thailand and the U.S.), and five more to host Expo 2030 (Italy, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Korea and Ukraine).

Dimitri Ketkenzes, BIE Secretary-General.

(Courtesy Expo 2020 Dubai.)

The evolution of Expos involves different forms of diplomacy and public diplomacy, which will be discussed in the next post of this series.

Lead image: The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, Crystal Palace, London, 1851. (Courtesy Expo 2020 Dubai.)

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

January 2

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.