Similar to many recently independent countries, densely populated Bangladesh strives to convey an attractive image to potential partners, seeking to enhance economic growth particularly through tourism. A variety of tools...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

China’s Digital Public Diplomacy Towards ASEAN Countries: How Beijing Frames the South China Sea Issue

On March 28, 2024, a significant diplomatic gathering occurred at the White House, where leaders from the United States, Japan, and the Philippines convened. Their aim? To address the mounting pressure exerted by the Beijing government on Manila concerning the contested South China Sea. President Biden reaffirmed the unwavering defense commitment of the United States and stressed, “United States defense commitments to Japan and to the Philippines are ironclad.” This renewed pledge reignited discussions about the seemingly serene South China Sea in Southeast Asia’s heart.

As Asia’s most significant political and military economy, China started upgrading its political claims on the South China Sea in 2011. It not only used the "nine-dash line" to demarcate geographical boundaries and establish jurisdiction over the entire South China Sea but also engaged in marine engineering and built artificial islands to expand its maritime territory. Although the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled in 2016 that Beijing’s nine-dash line boundary theory had no legal basis, the geopolitical undercurrents of the South China Sea dispute have not ceased. Events from the 2020 maritime standoff between Malaysia and China to the recent agreement between the Philippines and the United States to expand Washington’s military footprint in response to potential military conflicts in the South China Sea all stem from China’s military establishment, recent expansion in this region, and increasingly explicit anti-U.S. political positions.

As early as February 4, 2023, during the closing ceremony of the 32nd ASEAN Coordinating Council (ACC) meeting, Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi, acting as Chair of ASEAN, emphasized the need for Indonesia to intensify efforts in negotiating a Code of Conduct (COC) to address disputes in the South China Sea. However, it was not until August of the same year, during a visit by the Chinese foreign minister to Singapore, that this initiative of ASEAN was positively responded.

Our focus lies on China’s digital public diplomacy strategy preceding its response to the COC negotiation proposed by ASEAN. We seek to comprehend how Chinese diplomatic missions and diplomats perceive the ASEAN South China Sea issue 18 months prior to August 2023 and how they are employing narrative strategies concerning the South China Sea and ASEAN relations.

ASEAN Toward China: The Middle Ground of the East-West State Power Game

China and ASEAN established diplomatic dialogue in 1996. Geographically, China shares borders with Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam and has adjacent seas with the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia, and Indonesia, leading to border disputes. The ASEAN region serves as a middle ground for power dynamics between Eastern and Western nations. From the proposal of the Asia-Pacific Rebalancing Strategy to the adjustment to the Indo-Pacific Strategy, the strengthening of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, and the proposal of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity, as well as corresponding strategies such as the Belt and Road Initiative, making it a focal point of geopolitical competition.

Moreover, the ASEAN region boasts the largest Chinese immigrant population globally. Despite racial tensions in many ASEAN countries, economic dominance shifted to the Chinese community, shaping a diverse societal landscape. China’s integration of immigration into its foreign policy, coupled with its focus on united front work, has shaped its public diplomacy tactics within ASEAN. Cultural affinity and a tempered negotiation approach have defined China-ASEAN multilateral relations, fostering a cordial communication strategy as a cornerstone of China’s public diplomacy in the region.

How did China tell South China Sea-related stories vis-à-vis ASEAN countries online?

An examination of 158 tweets from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs unveils a strategic shift in how Chinese diplomats convey their political stances and initiatives through various text formats. First, diplomats from Beijing predominantly utilize “text accompanied by static images” to disseminate factual information concerning the South China Sea matter. Second, when expressing specific claims and viewpoints, Chinese officials opt for “text only posts” to underscore the significance of the content itself. Additionally, there is a growing trend of “text paired with live video streaming” content within Beijing’s digital public diplomacy efforts. This trend aligns with the popularity of short-form videos and live streaming in China, notably on platforms like TikTok. Such an approach allows for a linear presentation of events, fostering direct online engagement and attracting external attention.

China’s integration of immigration into its foreign policy, coupled with its focus on united front work, has shaped its public diplomacy tactics within ASEAN.

Furthermore, China strategically opted to mitigate geopolitical divisions associated with the South China Sea in its narrative approach toward ASEAN. In general, Beijing’s narrative strategy revolved around two primary axes. First, it underscored China’s commitment to peaceful and amicable international cooperation (n=74) as a significant regional power, employing various narrative tactics and initiatives to convey this message. Additionally, it advocated for mutual trust and solidarity among regional nations, substantiating its contributions to regional prosperity with factual shreds of evidence. Second, Beijing attributed the South China Sea dispute to Western attempts to destabilize the Asian region and cast China as a geopolitical adversary. Over 25.9% of the narratives (n=41) criticized Western interference in ASEAN politics.

In particular, when advocating and promoting for increased dialogue and bilateral or multilateral cooperation between China and ASEAN, Beijing often used slogan-based messaging. For instance, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying frequently tweeted slogans promoting solidarity and cooperation between China and ASEAN to underscore China’s active engagement and friendly disposition toward regional affairs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Text-only tweets published by Hua Chunying

Figure 1. Text-only tweets published by Hua Chunying

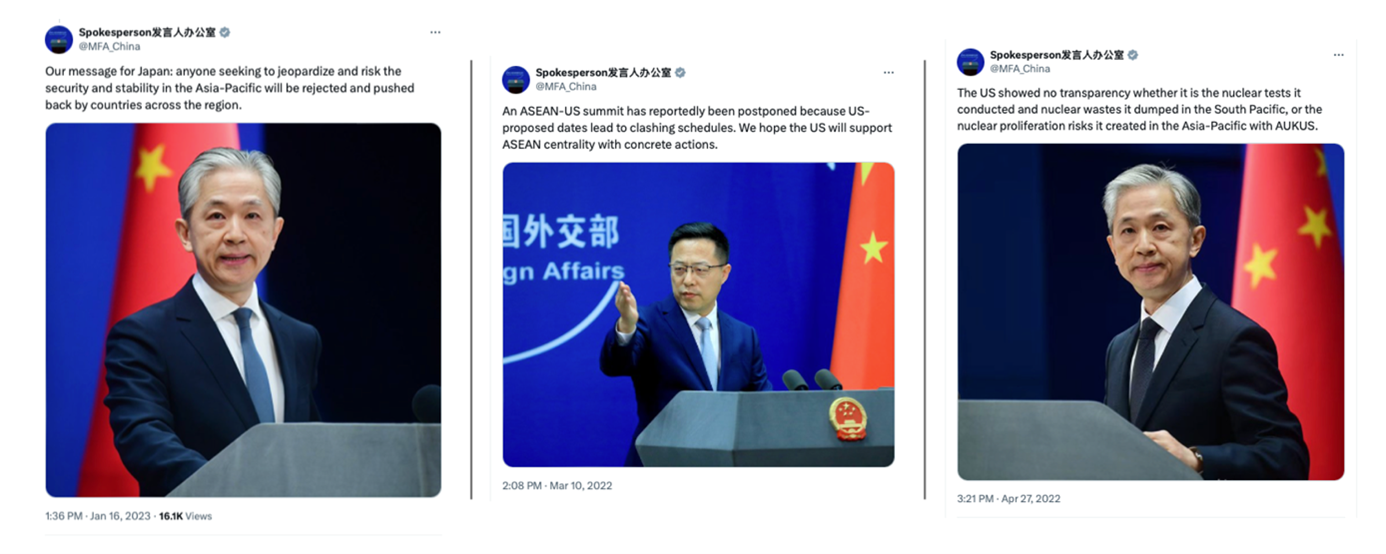

Moreover, when leveraging ASEAN as a platform for criticizing Western interference in regional affairs or challenging the legitimacy of Western influence in the ASEAN region, Chinese diplomats commonly used text combined with static images. In such narratives (see Figure 2), Beijing public diplomacy actors often incorporated portraits of foreign ministry spokespersons to lend an official and authoritative tone to its discourse. This approach conveyed the narrative content in a formal and official manner, implying China’s earnest and serious stance on the issues being addressed.

Figure 2. “Text + static image” modality in the tweets to criticize Western governments

Figure 2. “Text + static image” modality in the tweets to criticize Western governments

By analyzing an 18-month sample of narratives from China, we found that the Chinese government’s limited engagement with Twitter’s interactive features in digital diplomacy reflected a hierarchical approach to managing external propaganda for public diplomacy. Furthermore, Beijing demonstrated adeptness in leveraging various thematic hashtags to validate its initiatives. For instance, #China and #ASEAN appeared frequently in Beijing’s narratives, while the South China Sea theme has been deliberately weakened and is rarely mentioned. Network analysis of the Chinese hashtags revealed that when discussing China’s relationships with ASEAN, Beijing often illustrated the potential contributions it could make to regional development, particularly in areas such as climate and environmental protection (e.g., #Environment, #ClimatChange) and infrastructure (e.g., #BeltandRoad, #BRI, #ASeanVision2025, #HighSpeedRail). In addition, narratives about China-Africa relations (e.g., #China, #African) appeared in some narratives to support China’s advocacy of win-win cooperation within the framework of multilateralism (e.g., #multilateralism). Finally, in the China-fabricated narratives related to the topic of the South China Sea, other multilateral organizations were mentioned by Chinese diplomats, notably #NATO, #AUKUS, #TPP and #CPTPP, often used by Beijing to attack these pro-U.S. organizations for excessive geopolitical interference in the South China Sea.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

January 2

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.