Thirty-three years ago on August 9, 1974, President Richard Nixon resigned the presidency. His name is mostly associated with Watergate scandal. Putting aside all details and controversy regarding Nixon’s politics — all that...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Guerrilla Public Diplomacy: An Interview with Francisco Altschul

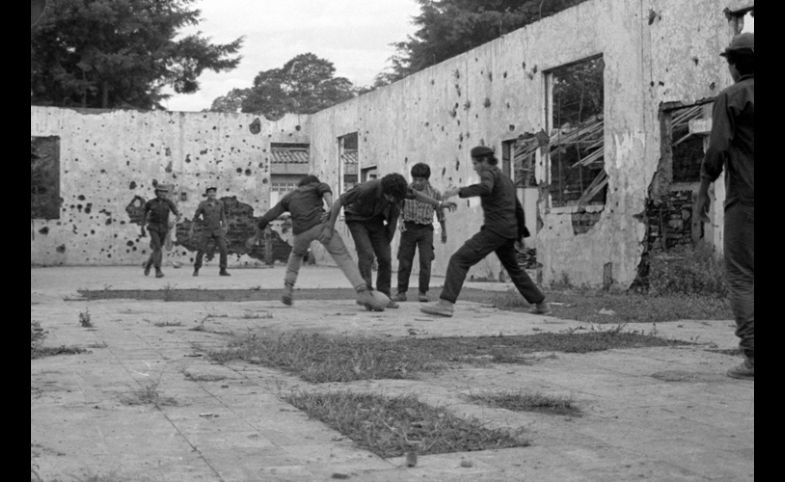

Francisco Altschul is one of the few diplomats in Washington D.C. who can brag about being both a representative of a guerrilla movement and a national diplomat at different times in his life. In the ‘80s, Altschul was a spokesperson for the Salvadoran insurgent coalition of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) and the Democratic Revolutionary Front (FDR) in the U.S. Currently, Altschul is the ambassador of El Salvador in Washington D.C., and represents the government of Salvador Sanchez Ceren, FMLN's former guerrilla commander.

Altschul talked to me about how the FMLN tried to influence U.S. policy during the Reagan administration. When Ambassador Altschul was representing the FMLN-FDR, it was at the height of the cold war. President Ronald Reagan viewed the FMLN-FDR as a communist insurgency backed by the Soviet Union and Cuba. Altschul describes the tactics of using public diplomacy and activist public relations to influence the debate on El Salvador in Washington D.C.

Ricardo Valencia: How did you end up in Washington DC in the 1980s?

Francisco Altschul: The FMLN-FDR political-diplomatic commission wanted somebody to work in the U.S. They wanted somebody fluent in English, with experience in the American way of life and so they approached me. I accepted because I felt that I could contribute to the Salvadoran process.

R.V.: How was your relationship with the FMLN general command in Mexico in terms of media relations and public relations?

F.A: It’s important to know that the FMLN-FDR had representation in Latin America and in Europe. These representatives worked both the solidarity and the diplomatic dimensions. In the case of the United States, the political-diplomatic commission decided to separate the diplomatic and the solidarity work. One dimension was the solidarity movement and the other worked strictly on the political and diplomatic efforts of the FMLN-FDR. It was the right decision, because, at the time, the United States was the adversary of the FMLN-FDR, and it was difficult to talk in the same conversation about stopping U.S. military and political support to the Salvadoran regime, and persuading the U.S. to support political negotiations.

As the representative of the political-diplomatic side, my work was fundamentally to educate the American population, but especially targeting opinion leaders, members of congress, academics, think tanks and the media.

R.V: Was your media strategy designed by the general command in Mexico or by the FMLN-FDR operators in Washington D.C?

F.A.: We had a lot of autonomy in terms of implementing the strategy. We received the information and orientation from the main office in Mexico City. However, we had a lot of freedom on how to move around. In regards to the media, we were trying to inform and educate. We did not want to be in the media all the time, but we looked for meetings with the editorial boards of U.S. newspapers in order to fundamentally change the image of the FMLN-FDR. In the media, the FMLN-FDR was described as a Marxist guerrilla organization. Of course, the image of a Marxist guerrilla is tied with the idea of camouflage and rifles, so we were trying to pitch the image that we could also dress in suits, speak in a moderate voice, and speak fluently in English. That simple thing changed many misconceptions about the FMLN.

R.V.: What was the difference in terms of media relations and communication between the political diplomatic commission and solidarity organizations such as the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES) at the time?

F.A.: First, CISPES was completely autonomous from the FMLN. It was a civil organization, but we provided analysis as we provided to many other organizations, think tanks and individuals. Mainly, as I mentioned, there was a difference between our goals and the solidarity movements' goals, which was fundamentally to stop U.S. intervention and financial support to the Salvadoran government. The FMLN-FDR's job was to promote and to sell the idea of the urgency of a political settlement in Washington, D.C. The basic idea was to make people understand that the best solution for everybody involved was the process of dialogue and negotiation, and that the FMLN was serious in its call for a political settlement, the idea of negotiations was not simple tactical move.

R.V.: What were the contacts or how was contact made between the FMLN and Reagan officials?

F.A.: In the final moments of the peace agreement, there was direct contact between the FMLN and the administration. But before that, we communicated with the administration through different parties, for example, members of congress who, eventually, would comment on our positions with administration officials. We were presented the different initiatives that the FMLN were bringing to the negotiation table.

Of course, the image of a Marxist guerrilla is tied with the idea of camouflage and rifles, so we were trying to pitch the image that we could also dress in suits, speak in a moderate voice, and speak fluently in English. That simple thing changed many misconceptions about the FMLN.

R.V.: My understanding is in the U.S., the FMLN-FDR focused on a small group of people -- decision-makers and opinion leaders, instead of trying to influence the entire U.S. population.

F.A.: That’s right. Our main job was to educate decision makers on the reality in El Salvador and then influence policy. Secondly, we promoted a negotiated, political settlement. We had contact with member of congress, editorial boards, think tanks, academics, universities and churches

R.V.: How difficult was it to sell the FMLN-FDR when the Reagan administration called it a terrorist organization?

F.A.: It was not easy, because simple labels are more effective than long arguments. The FMLN-FDR was a coalition of different organizations, some of them had Marxist orientations, but others were Social Democrats and Social Christians. We explained that we were a pluralist organization with different points of view. It was an organization that comes from inside El Salvador; not the result of a foreign intervention be it the Soviets, Cubans or Nicaraguans, as it was generally portrayed. And more importantly, that we had resorted to armed struggle as a last resort, because all democratic spaces had been closed to us. We were fighting for democracy; we were the real freedom fighters.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.