Mixing religion and public diplomacy can produce volatile results, but in a world in which the dissemination and influence of religious beliefs are enhanced by new communications technologies, religion is a factor in most...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

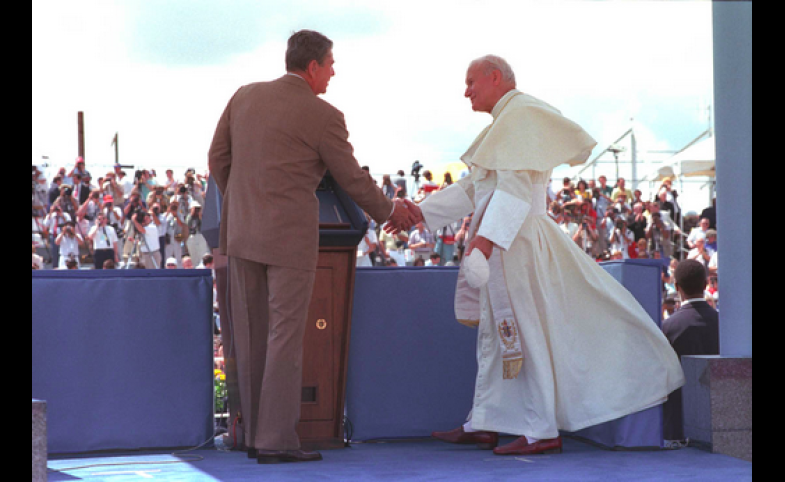

Popes and Presidents Can Make a Powerful Team

St. Peter’s Square teemed last weekend with believers witnessing the extraordinary canonization of two contemporary popes, John XXIII and John Paul II.

Americans who are critical of the church, its failings and even the sanctification process focus on recent scandals and exclusionary practices. Without minimizing these criticisms, there should also be a secular recognition of these two past popes’ international achievements, remembering that they both partnered with U.S. presidents to positively change the course of global events.

Whether helping to prevent a hot war or to end the Cold War, these two popes worked with Presidents John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan to achieve peaceful outcomes.

Pope Francis’ ascension to St. Peter’s throne creates unique opportunities for President Barack Obama to leverage a fresh, credible message of social justice and leadership aimed at Latin America. If pursued, it could be the latest collaboration between a president and a pope and potentially change the face of the Southern Hemisphere.

Rome and Washington, D.C., do not always see eye-to-eye, as during World War II or the two Vatican-opposed Iraq wars.

But ever since Woodrow Wilson’s first meeting with Pope Benedict XV in 1919, shared foreign policy goals between the White House and Vatican have often achieved success.

In October 1962, John XXIII played an effective intermediary role between Kennedy and then-Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in the heat of the Cuban missile crisis. More recently, John Paul II was the unelected, morally superior Polish opposition leader in absentia. He offered hope, peaceful resistance and a path to freedom from Soviet captivity.

I experienced the power of John Paul II’s papacy as a reporter covering his Rome meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev in 1989 – the visit itself was recognition that the pope led vast spiritual divisions. Months later, I stood amidst reverent throngs at John Paul II’s post-revolutionary victory tour to Czechoslovakia. A profound shift had taken place.

John Paul II did not act alone. As Carl Bernstein reported in “The Holy Alliance,” a 1992 Time magazine cover story, “Reagan and the pope agreed to undertake a clandestine campaign to hasten the dissolution of the communist empire.” Together they succeeded.

It is easy to bristle at the idea of a religious leader conspiring with a U.S. president. Faith in the U.S. Constitution means for most a belief in the absolute separation of church and state. But church and state sometimes need to work together to change big things.

Today, there is an opportunity for positive change in Latin America. The region is rife with corrupt and powerful populists. Exploiting the weak and preying on their passions, some of these leaders were criticized years ago for their “exhibitionism” by the man who is now Pope Francis. The first Latin American pope’s influence amongst Catholics in the Americas is comparable to the first Polish pope’s popularity behind the Iron Curtain.

Where Francis is finding fertile ground, however, the heavy hand of past U.S. interventions is still felt throughout the continent. The 1973 CIA actions against Chile’s Salvador Allende or the more recent Washington support for opponents of Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez still whips people up down south.

Grenada, Cuba, Panama, Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, Mexico, Bolivia, Colombia – there’s a long list of countries where the U.S. has engaged directly in war, supported authoritarian regimes, overthrown leaders, secretly armed groups or feigned ignorance of death squads.Throughout the region, the U.S. propped up reprehensible military leaders and created long-lasting resentments. Uncle Sam became an easy target for anti-Yankee rhetoric and attitudes.

Today, despite wariness toward U.S. engagement, there is still an opportunity to confront and counter new challenges and foreign alliances being forged in Latin America. Both the passage of time and President Obama’s light touch play a role in softening the Yank’s image. During his recent Asia trip, the president characterized his foreign policy approach as hitting singles and doubles. “Every once in a while, we may be able to hit a home run,” he said.

It may now be time to swing for the fences and for Washington to increase quiet coordination with the Vatican.

The president shares a passion and a purpose with Pope Francis. They are both committed to combating inequality. Francis offers a credible alternative voice to the loud populist leaders who trade on angry rhetoric to achieve authoritarian rule. A more prosperous and equitable Latin America would be a homer.

This piece was orginally published by The Sacramento Bee.

Read the orginal article here.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.