“The challenge of Russia disinformation is not about Donald Trump,” said Ohio Republican Senator Rob Portman as he kicked off a day-long conference on Russian disinformation last month. Narrowly speaking, that may be true...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Russia’s Wicked Power in the 2016 U.S. Election

Over 200 years ago, President George Washington warned Americans about foreign powers undermining American democracy by tampering “with domestic factions, to practice the arts of seduction, to mislead public opinion, to influence or awe the public councils.”

In the present, we are finding that old threats are new again as the United States is challenged by Russia’s strategic communication efforts targeting both our domestic politics and international interests.

Recent surveys from YouGov and Pew Research have shown that President Vladimir Putin’s favorability and Russia’s positive image have grown considerably among Republicans and Trump supporters (though still a net negative). However, Russia’s goals are not greater attraction and credibility, but rather the opposite: sowing disinformation, distrust, and dislike amongst its targets. Unlike a “soft power” strategy employed by the United States, Russia’s public diplomacy strategy is asymmetrical—what could best be called “wicked power.”

This strategy has a long legacy, with “active measures,” “dezinformatsia,” “kompromat,” and “useful idiots” regularly employed by the Soviet Union throughout the Cold War. It is no accident that a president who is a former KGB officer has focused on reviving and strengthening Russia’s capabilities in this area.

Russia’s “wicked power” and Cold War strategies have been greatly aided and abetted by two global trends over the last decade. The first is the rise of penetrating and ubiquitous communication technologies which Russia has co-opted to globally spread false or misleading information. The second is a global crisis of public faith in Western liberal democracy. This includes deepening political polarization, less confidence in established political institutions and the mass media, populism, the rise of right-wing nationalism, and the questioning of an open cosmopolitan global order in many developed democracies, including the United States.

The latter trend is what really empowers Russia’s strategic communication efforts, by providing fertile ground for disinformation and distrust—whether it is spread by Russia, non-state actors such as ISIS, or nationalist or right-wing movements in the United States and Europe.

Russia’s “wicked power” is not just about promoting false information and influencing voter preferences—it also aims to attack democratic institutions themselves.

To examine Russia’s “wicked power” more closely in the context of the recent U.S. election, our research team at Ohio State University conducted a national post-election survey of nearly 2000 Americans in December 2016 and early January 2017.

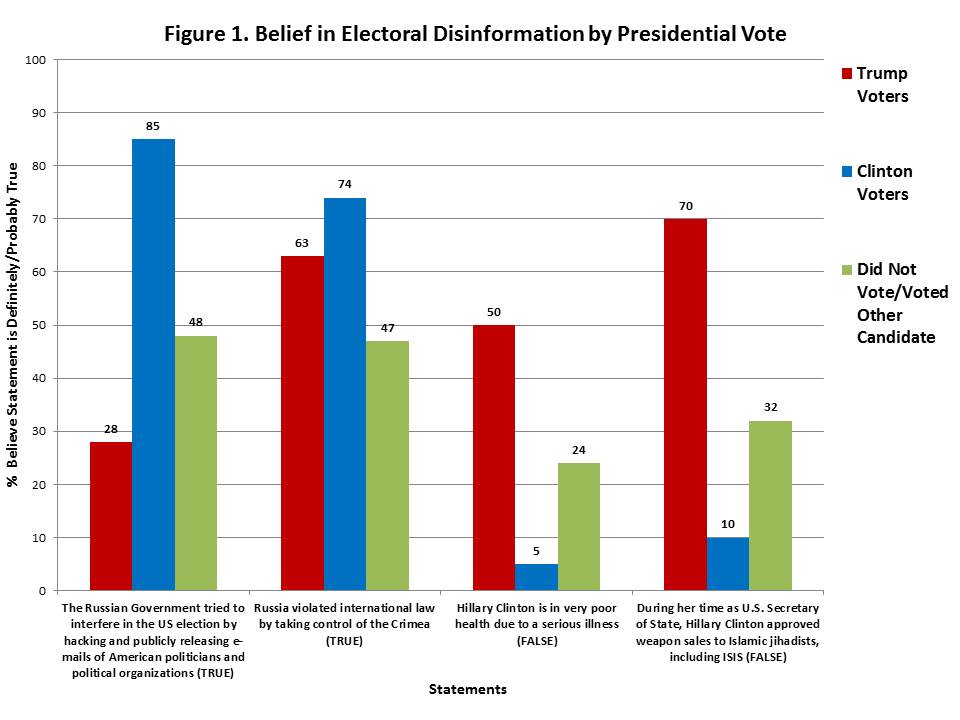

We asked respondents to answer whether a series of four statements reflecting electoral disinformation promoted directly or indirectly by Russia were true or false.

The results of our survey are shown in Figure 1 below. For example, we asked Americans whether “the Russian Government tried to interfere in the US election by hacking and publicly releasing e-mails of American politicians and political organizations.” 54% of respondents said this statement was definitely or probably true, whilst 29% said it was definitely or probably false. However, as the figure below illustrates, the perceived veracity of this statement varied greatly by voting preference. 28% of Trump voters believed this statement was true, compared to 85% of Clinton voters.

The other statement directly concerning Russia was whether Americans believed “Russia violated international law by taking control of the Crimea.” This statement reflects the Obama administration’s messaging about the conflict between Ukraine and Russia and the basis for the sanctions placed on Russia since 2014. In contrast, Trump has had contradictory messaging about Russia and Crimea, and suggested he would legally recognize the Russia’s annexation.

This contrary messaging is reflected in our poll results. 74% of Clinton voters believed this statement was true, in comparison with 63% of Trump voters (overall 62% of all Americans in our poll believed this statement was true).

These results highlight a key challenge for U.S. public diplomacy moving forward. If the American government has trouble convincing a sizable portion of its own citizens that Russia violated international law when it took over Crimea, how does American public diplomacy effectively convince foreign publics of the same?

Hillary Clinton was the primary target of Russian disinformation efforts during the 2016 election campaign. We asked Americans about two false statements about Hillary Clinton that were promoted through Russian-influenced social media and by information that was posted on Wikileaks as a result of Russian hacking. The first false statement was “Hillary Clinton is in very poor health due to a serious illness.” Overall, 26% of Americans believed this statement was true. 50% of Trump voters believed that Clinton was seriously ill, compared to 5% of Clinton voters.

The second statement was “During her time as U.S. Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton approved weapon sales to Islamic jihadists, including ISIS” was believed by 70% of Trump voters and 10% of Clinton voters. 37% of all voters believed this statement was true.

Belief in Russian-sponsored disinformation is driven by a loss of faith in traditional institutions like political parties and the news media and deep political polarization, and our own biased need for confirmation of our partisan attitudes. Yet Russia’s “wicked power” is not just about promoting false information and influencing voter preferences—it also aims to attack democratic institutions themselves.

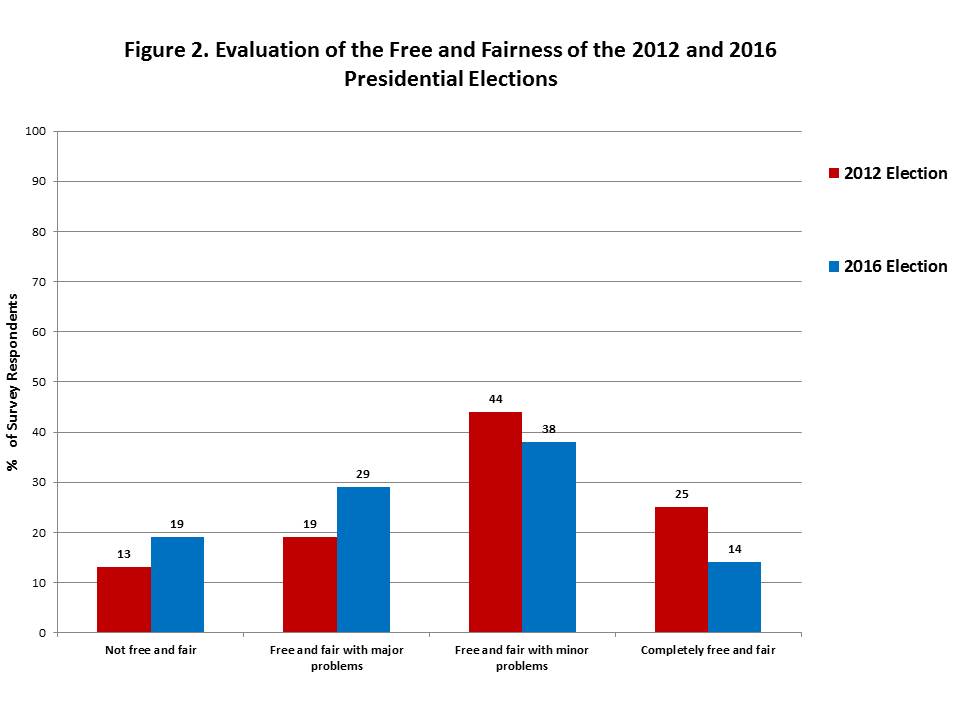

For example, in our poll we asked respondents how they would rate the fairness of the 2016 presidential election and compared their responses to similar data we collected shortly after the presidential election in 2012. The figure below shows the results.

In 2012, about one-quarter of Americans believed the presidential election was completely free and fair, compared to a much lower 14% of Americans in 2016. Likewise, the number of Americans who believed the election was not free and fair or had major problems more than doubled from 22% in 2012 to 48% in 2016.

Collectively, these survey findings demonstrate Russia’s effectiveness in co-opting the deep political divide in the United States to promote its interests in Eastern Europe and discredit a presidential candidate seen as hostile to its foreign policy goals.

However, what is truly “wicked” about Russia’s strategic communication is its potential to undermine public confidence in democratic institutions and elections—and in turn attack the foundations of Western liberal democracy as we know it.

*The survey referenced in this article was funded by the Ohio State University as part of the Comparative National Elections Project (CNEP) hosted at the OSU Mershon Center for International Security Studies. This was a nationally representative online survey of 1950 respondents conducted by the polling firm YouGov with an AAPOR response rate of 27%.

Photo by En.Kremlin.ru I CC 2.0

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

January 2

-

February 6

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.