In recent years, Beijing’s approach to fostering cooperation with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has centered on four instruments of Eytan Gilboa’s public diplomacy concept: advocacy, broadcasting, public...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

New President “Jokowi” Needs to Revamp Indonesian Public Diplomacy

Indonesia was gripped by election fever over recent months, with talk of the impending election of a new president on the population’s lips. Unsurprising, since this person will lead the world's third largest democracy and a rising power closely watched internationally. With 185 million voters marking their choice across over 6,000 islands, and with the number of polling workers equalling the entire population of Ireland, the election in Indonesia was a massive undertaking [1]. It was, above all, a big deal in terms of its symbolic meaning.

The presidential race between the two strongest candidates, Jakarta Governor Joko Widodo, better known as Jokowi, and retired General Prabowo Subianto, not only offered Indonesians an option between divergent governing styles but also implied a symbolic choice. The vote could mark the beginning of what some consider “a historic moment for Indonesia, - a fresh break from a political system entwined with the established oligarchy dominating Indonesian politics for the last four decades.” [2]

According to the somewhat Jokowi-leaning The Economist, “he will be unlike any leader modern Indonesia has had before, coming from neither the armed forces nor an established family.” Jokowi indirectly encouraged this image by stating in his campaign that he intended to forge a different path for Indonesia, while suggesting that this could only be achieved by someone who was not hostage to the past. [3]

If his election rhetoric is translated into deeds, many believe his victory could indeed become a symbol of Indonesia’s new political direction, with a “man of the people” at the helm. It took two nail-biting weeks after voting ended on July 9th to learn the official results.

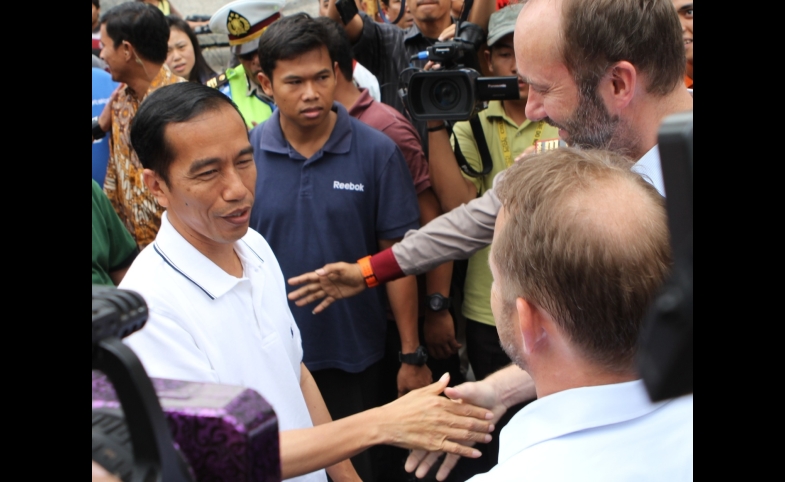

Yet in the midst of the election fever, speculation, and politicians’ shaking of millions of hands, I wondered if the attention paid to the Indonesian public during the election was of a temporary nature or not. Was it just lip service, as seen in many other elections across the globe, or was it an indication of a “new normal?”

I therefore wrote the following article for Indonesia’s (inter)national newspaper The Jakarta Post, “Does the public matter after election time?”. It briefly reflects on the campaign and on why the president-elect must continue public outreach, including involving citizens in international policy through public diplomacy, especially after election time. The article also looks critically at Indonesia's public diplomacy development, its past, present, and future, including the challenges it faces to adjust to Indonesia's evolving role as a rising power.

After the Jakarta Post piece was already published, the Indonesian election committee confirmed on the evening of July 22 that Jokowi had garnered 53% of the votes, or 8 million more than Prabowo Subianto, who garnered 47%. Jokowi is therefore the President-elect and will be sworn in no later than October 20.

There was no time for the President-elect and his followers to crow victory, however. Prabowo rejected the results, claiming that “the election had been flawed and riddled with fraud.” Though some Jokowi supporters remain uneasy with this turn of events, analysts have noted that “given the 6% victory margin, Prabowo is unlikely to successfully contest the outcome with the Constitutional Court.” Yet as this is a first for the latter, the Court’s decision will be one more test of Indonesia’s young democratic system. [4]

Despite this, Jokowi’s victory is quite remarkable. One must not forget that Indonesia’s new president is a former furniture builder who rose through popular elections to the post of mayor of the town of Solo in central Java and then to governor of the capital, Jakarta. As The Economist points out: “He did not emerge from the cronyism of Indonesia’s political business elites, but out of the Reformasi movement.” In this context, “Indonesia’s decentralised democracy, which provides greater authority to local governments, out of which Jokowi emerged, can take some credit for his ascent to the presidency.” [5]

While the future remains murky, Jokowi is known as a “man of the people” who is considered approachable by Indonesian citizens. [6] Expectations are high that he will continue with his bottom-up (Blusukan) people-centered approach, and transfer this attitude into the policy making process, hopefully including international policy.

While Jokowi may not have expressed any outspoken views or concrete vision on international policy, there are some indications he will lean towards the practice of public diplomacy. For example, he pleaded in favour of “involving people’s participation in the formulation and implementation of foreign policy” in his vision-mission paper (see the General Elections Commission website). Also, apparently a part of the mission is enhancing the diplomatic infrastructure of the Foreign Affairs Ministry, such as expanding its internal research capacity through rearrangement of priorities and organisational structure; and enhancing public diplomacy especially so as to widen public participation in foreign affairs. [7]

In short, his personal style of public outreach and his allusions to involving the public in international policy making and conduct through public diplomacy supported by a reorganization of the Foreign Affairs Ministry, and his past experiences with local governments, seem to be promising avenues for the future of Indonesia’s public diplomacy and the changes within it, as described in the Jakarta Post article. By digging Indonesian public diplomacy out of its stagnation and revamping it, it will inspire others in the region and beyond as it has done before.

For all his apparent potential, Jokowi will have his hands full, including in public diplomacy, before he can truly be considered “a break from past political directions.” [8] Only when – and if – the millions of handshakes he shared during and after the election result in concrete public diplomacy deeds will his victory become more than symbolic and “a testament to Indonesia’s democratic vibrancy.”

[1] Fransiska Nangoy and Kanupriya Kapoor, "In contested election, Indonesia's democracy on the line," Reuters, July 12, 2014.

[2] Michael Safi, Claire Phipps, "Indonesia election 2014: Jokowi and Prabowo both declare victory - as it happened," The Guardian, July 9, 2014.

[3] The Economist, "Fanfare for the common man," July 26, 2014.

[4] The Jakarta Post, "Jakarta, Election Watch," July 22, 2014; The Economist, "Jokowi’s day. Though his opponent attempts to spoil it," July 26, 2014.

[5] The Economist, "Fanfare for the common man," July 26, 2014.

[6] The Economist, "Banyan: No Ordinary Jokowi," January 18, 2014.

[7] Emirza Adi Syailendra, "Indonesia’s Post- Election Foreign Policy: New Directions?," S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Commentaries, NTU, No. 113/2014, June 13, 2014; Meidyatama Suryodiningrat, "Jokowi: the foreign policy president," The Jakarta Post, May 26, 2014; Yayan GH Mulyana, "Electoral debates and foreign policy," The Jakarta Post, June 4, 2014.

[8] The Economist, "Fanfare for the common man," July 26, 2014.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

January 2

-

February 6

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.