As Expo 2020 Dubai grows closer, we're delighted to share some of CPD's work at past expos highlighting the role of student ambassadors who bring visibility to American culture through in-person connections. The USA...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

From the "Kitchen Debate" to "Feeding the World"

“We are one in nine billion,” states a striking stainless steel sculpture at the entrance to the U.S. Pavilion at Milan Expo 2015: “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life,” which opened on May 1 and runs through the end of October. That visual statement is intended to get visitors thinking about the fact that in 2050, the world’s population is estimated to reach 9 billion, and more sustainable ways to feed people must be found.

To help present the U.S. Pavilion’s theme, “American Food 2:0: United to Feed the Planet," 120 bright young Americans from 35 states and 96 universities will serve as representatives of America at the pavilion. The group includes students conversant in 26 languages. Twenty million visitors are expected at Expo Milan during its six month run and these designated Student Ambassadors will welcome visitors and “put a living face on the experience," according to Jerry Giaquinta, Professor at the University of Southern California’s Marshall Center for Management Communication, who is serving at Chief Communication Officer for the U.S. Pavilion and was in charge of the student selection and training process.

The first student ambassador I met while visiting the U.S. Pavilion was Peter Schoemer, who just happened to be from the Pittsburgh area, where I grew up, and was studying culinary arts at Drexel University in Philadelphia. Erineka Mulligan, a student at Louisiana State University, was demonstrating an interactive display that invites visitors to experience the challenges of food production and distribution. Stafford Newsome (pictured below), a Florida native heading into his senior year at Brigham Young University, walked me through an animated series of vignettes highlighting the diversity of American food coming from cultures around the world. In conversation, I learned that he spoke Russian and Ukrainian, two of my own foreign languages, and had spent two years in Ukraine as a Mormon missionary.

U.S. Student Ambassador Stafford Newsome photographed by author

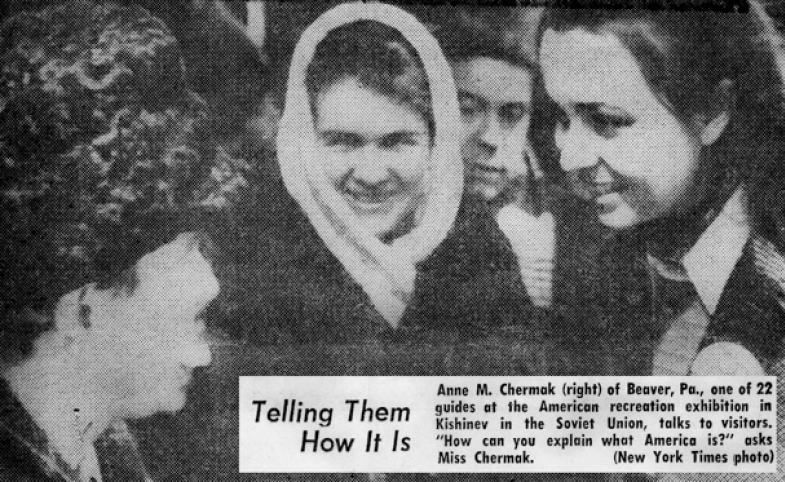

Watching the young guides in action, greeting visitors and explaining the interactive elements in the U.S. pavilion, brought to mind my own experience back in the ‘70’s, when I had just graduated from college and was selected to serve as one of 22 young American guides, all fluent in Russian, for a large U.S. government exhibit in the Soviet Union.

Our exhibit was one in a long series that began in 1959 in Moscow, best known for the famous “kitchen debate” between Vice President Nixon and Soviet Premier Khrushchev.

Those exhibits, with a new theme each year, were our showcase public diplomacy programs in the USSR during the Cold War. The theme of our exhibit was "Outdoor Recreation, USA," and upwards of 15,000 visitors lined up daily, waiting three hours in the bitter cold for a chance to walk through our exhibit, learn something new about life in America, and engage in conversation with a living, breathing young American.

For most, we were the first Americans they had ever met. At a time when news and information were strictly controlled by the Kremlin and the only access to Western news was via scratchy short wave radio broadcasts that the Soviets did their best to jam, these encounters were something quite extraordinary. Many of us who served as guides, including myself, went on to careers in the U.S. Foreign Service.

Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, the sense in the U.S. Government was that, since we’d won the Cold War, there was no more need for this type of public diplomacy, and the exhibits program was disbanded. Not only was the exhibits program eliminated, but in 1991, Congress passed legislation barring the U.S. Government from funding participation in international expositions. Any official U.S. presence would heretofore have to be funded entirely by the private sector.

Several international expos came and went with paltry U.S. participation, or none at all. The private sector was just not able to pull together the resources necessary to fund and manage a U.S. pavilion. Plus, in the digital age, with instant global connections via the Internet, weren’t these types of international exhibitions obsolete?

In 2010, the U.S. Pavilion at the Shanghai Expo came together just in time, beset by fund-raising and other obstacles, and the Mandarin-speaking American Student Ambassadors were praised as by far the best thing about the U.S. presence. Fast forward to 2015 and Expo host Milan, Italy. The goal of this Expo, with the compelling theme of how to feed the planet, is to engage participants in dialogue and develop strategies to improve the environment and the quality of life, centered on food. What an extraordinary opportunity for multi-dimensional public diplomacy, involving governments and an international public of all ages and backgrounds. Is not such an opportunity to deal with one of the most compelling issues of our time worthy of American government financial support?

Why not make U.S. participation in international expositions a financial partnership between the USG and the private sector, instead of putting all the burden to fund-raise an estimated $60 million to design, construct, and staff a pavilion and all its contents on private citizens and corporations? The past two decades since the end of the Cold War have clearly shown that the need for U.S. public diplomacy and “telling America’s story to the world” is greater than ever.

A clear message of this Expo is that even in the Internet age, people hunger for direct human connection and experience, and that 20 million people passing through an Expo are multipliers who will remember and share that experience with at least one other person, not to mention the multiplier effect through social media.

Just as we guides were in the 1970’s in the USSR, today’s student ambassadors at the U.S. Pavilion at Expo Milan are a valuable resource for just that kind of vital human connection, what the illustrious director of the U.S. Information Agency during the Kennedy Administration called, “the last three feet,” the space between people in direct conversation.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.