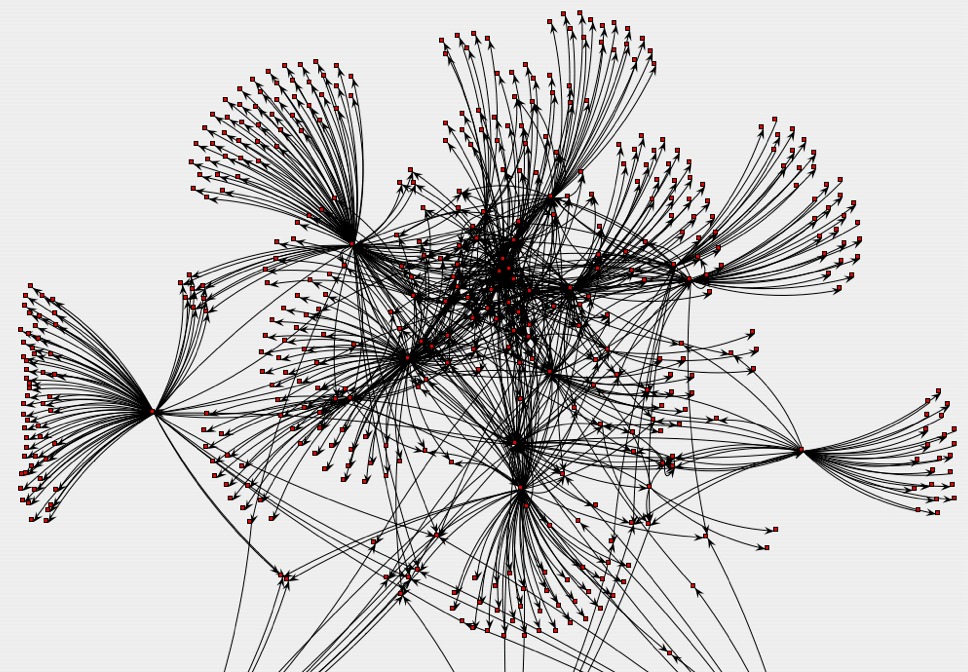

In a recent post on the CPD blog, Prof. Corneliu Bjola analyzed NATO's social media presence. The results of his analysis suggest that NATO's Twitter account is a bubble of sorts, as it is followed mainly by users from NATO...

KEEP READINGThumbnail Image:

Introducing the Digital Diplomacy Bibliography

Digital social media technologies have become part of people’s everyday life. They also have an impact on diplomatic practice and the way governments engage foreign publics. The conduct of diplomacy is ever more public and global. While the fundamental purpose of diplomacy remains the same, these new and emergent communication platforms are forcing us to rethink the structures and processes of diplomatic work. It is increasingly simple for governments to directly reach a broad international audience, whilst non-governmental actors and even individuals are empowered by interactive and instantaneous communication. Digital diplomacy presents tremendous opportunities for global engagement, but it also generates new problems and challenges. Determining digital technologies’ effects on diplomacy and international communication, and these technologies’ ability to strengthen networks and relationships, is a new frontier in public diplomacy work and diplomatic studies.

To facilitate the debate and study of this unfolding phenomenon, the USC Center on Public Diplomacy (CPD) and the Netherlands Institute of International Relations, Clingendael, are pleased to announce the joint publication of the Digital Diplomacy Bibliography. In the years ahead, both CPD and the Clingendael Institute will conduct research on diplomacy and public diplomacy in the digital age, and in the spirit of enhanced communication, we intend to share our findings at an early stage. The current edition of the Bibliography covers recent academic studies and practitioners’ discussions on topics related to digital diplomacy.

We would like to thank Sohaela Amiri and Martijn van Lith for providing invaluable research support in compiling the bibliography, and to Colin Hale for his graphic design. Special thanks to Craig Hayden for his review and suggestions.

Jay Wang, Director, USC Center on Public Diplomacy @publicdiplomacy

Jan Melissen, Senior Research Fellow, the Clingendael Institute, Professor of Diplomacy, University of Antwerp @JanMDiplo

To download the full Digital Diplomacy Bibliography, click here.

Books on Digital Diplomacy

ABOUT: The evolution of modern technology has allowed digital democracy and e-governance to transform traditional ideas of political dialogue and accountability. This book brings together a detailed examination of the new ideas on electronic citizenship, electronic democracy, e-governance, and digital legitimacy. Combining theory with the study of law and of matters of public policy, this is an essential read for academic and legal scholars, researchers, and practitioners.

Chopra, S. (2014). The Big Connect: Politics in the Age of Social Media. Random House India.

ABOUT: Are digital means of communication better than traditional bhaashans and processions? Will a social media revolution coerce armchair opinion makers to head to poll booths? Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn are changing the way the denizens of the world, and more specifically youth of this country, communicate and connect. In this book, Shaili Chopra traces the advent of social media in India and how politics and lobbying have now shifted to the virtual floor. She argues that though a post, a pin, or a tweet may not translate into a vote, it can definitely influence it. With comparisons to the Obama campaign of 2008 and 2012 and analysis of the social media campaigns of political bigwigs like Narendra Modi, Rahul Gandhi, and Arvind Kejriwal—the book discusses the role of a digital community in Indian politics.

Costigan, S. S. (2012). Cyberspaces and Global Affairs. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

ABOUT: From the "Facebook" revolutions in the Arab world to the use of social networking in the aftermath of disasters in Japan and Haiti, to the spread of mobile telephony throughout the developing world, these developments are part of how information and communication technologies are altering global affairs. With the rise of the social media, scholars and practitioners of international affairs are adapting to this new information space across a wide scale of issue areas. In conflict resolution, dialogues and communication are taking the form of open social networks, while in the legal realm, where cyberspace is largely lawless space, states are stepping up policing efforts to combat online criminality and hackers are finding new ways around increasingly sophisticated censorship. The essays and topical cases in this book explore such issues as networks and networked thinking, information ownership, censorship, neutrality, cyberwars, humanitarian needs, terrorism, privacy and rebellion, giving a comprehensive overview of the core issues in the field, complemented by real world examples.

ABOUT: This working paper series intends to illuminate this narrative by delving further into the trends in international affairs that have been accelerated or otherwise augmented by the information revolution. Because this task could easily prove unmanageable, the series will examine in particular two separate but linked phenomena enhanced by the information age: heightened transparency and increased volatility.

ABOUT: In light of the events of 2011, this book examines how diplomacy has evolved as media have gradually reduced the time available to policy makers. It analyzes the workings of real-time diplomacy and the opportunities for media-centered diplomacy programs that bypass governments and directly engage foreign citizens.

ABOUT: Inspired by Allan Gotlieb's capacity to reshape diplomacy for the times, the contributors to this volume grapple with the challenges of a digital age where information is everywhere and confidentiality is almost nowhere. With an introductory essay by renowned political scholar, writer, and commentator, Janice Gross Stein, the work is divided into 4 sections: Diplomacy with the United States in the Era of Wikileaks; The Professional Diplomat on Facebook; Personal Diplomacy in the Age of Twitter; and Where is Headquarters? Contributors include professional diplomats, award-winning journalist Andrew Cohen, former Globe and Mail editor and author Ed Greenspon, and Allan Gotlieb's wife and partner in 'social diplomacy', Sondra Gotlieb.

ABOUT: Over the past decade, scholars, practitioners, and leading diplomats have forcefully argued for the need to move beyond one-way, mass-media-driven campaigns and develop more relational strategies. In the coming years, as the range of public diplomacy actors grows, the issues become more complexly intertwined, and the use of social media proliferates, the focus on relations will intensify along with the demands for more sophisticated strategies. These changes in the international arena call for a connective mindshift: a shift from information control and dominance to skilled relationship management. This book is an essential resource to students and practitioners interested on how to build relationships and transform them into more elaborate network structures through public communication. It will challenge you to push the boundaries of what you think are the mechanisms, benefits, and potential issues raised by a relational approach to public diplomacy.

Journal Articles on Digital Diplomacy

ABSTRACT: Based on a range of interviews with foreign diplomats in London, the article explains the considerable variation in the way communication technologies both affect diplomatic practices and are appropriated by diplomats to pursue the respective countries’ information gathering and outreach objectives. The study shows that London, as an information environment, is experienced differently by each of the diplomats and embassy actors. The analysis elaborates a model of the “communication behaviour” of foreign diplomats in London based on an evolutionary analogy: foreign diplomats in the context of the British capital, within their respective embassy organizations, can each be compared to the members of a species attempting to survive in a natural environment. The nuances highlighted by the explanatory model challenge the largely homogeneous and generalized nature of current debates about media and diplomacy, as well as public diplomacy.

ABSTRACT: Due to the ongoing information revolution, diplomats find themselves in an increasingly competitive information-intensive environment where they have to prove that they still are relevant and needed. The article explores this general development by detailing how the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) has related to the technological challenge. Drawing on personal interviews with MFA staff, study of MFA documents including reports from Norwegian embassies and delegations, as well as participant observation, reasons for the relative tardiness and path-dependence in implementing IT-supported organizational change at the MFA are explored.

ABSTRACT: To meet its most important strategic goals—on global warming, the continuing economic crisis, nonproliferation and a host of regional issues—the State Department will require a practical, pragmatic digital strategy of the sort that Barack Obama employed to win the presidency.

ABSTRACT: The article discusses a study which examines the utilization of Web 2.0 technologies in the proliferation of Grey Literature in the U.S. government. It notes that the U.S. Department of State has embraced the transformation of internal and external communication towards eDiplomacy. It explores the functionality of federal government electronic models and the various ways they produce information for intra-governmental communication services and external users of information.

ABSTRACT: In recent years the United States has turned to digital technologies to buoy its response to anti-Americanism in the so-called “Muslim world.” At least three concepts appear to be shaping this effort. The first is a marketing-based strategy called “engagement.” The other two are derivations of Marshall McLuhan's “global village” and his aphorism that “the medium is the message.” This article focuses on the uses and misuses of McLuhan's work by foreign policy officials in Washington. It argues that their stated purpose—to empower people and further inter-cultural understanding through dialogue—is dubious. Indeed, pronouncements regarding these potentials now sit uncomfortably alongside Washington's use of these same technologies to manage dissent. By assessing digital engagement and a more general initiative called “internet freedom” (both in the light of what McLuhan, in fact, says), American aspirations involving digital communications are shown to be more than just contradictory; they are dangerously misguided.

ABSTRACT: The Obama administration has embraced ‘engagement’ as the dominant concept informing U.S. public diplomacy. Despite its emphasis on facilitating dialogue with and among Muslims overseas, this article demonstrates that, in practice, engagement aims to leverage social media and related technologies to persuade skeptical audiences to empathize with American policies. Indeed, its primary means of implementation – participatory interactions with foreign publics – is inherently duplicitous. Through the authors’ description of how engagement is rooted in long-standing public relations and corporate marketing discourses, and in light of the historical and structural foundations of anti-Americanism, this contemporary public diplomacy strategy is shown to be both contradictory and, ultimately, delusional. As an alternative, the authors argue that an ethical public diplomacy should be pursued, i.e., a public diplomacy that embraces genuine (rather than contrived) dialogue. Although this approach is difficult to achieve (primarily because it implies a direct challenge to entrenched U.S. foreign policy norms), it constitutes a mode of public diplomacy that better reflects the idealized principles of American democracy.

ABSTRACT: Networks and connectivity, rather than specific platforms or technologies, are the hallmarks of the globalization age. The concept of the V Tower embeds these qualities, as well as the nature, culture, and content of the enabled activity. By favoring these elements over the previously unassailable characteristics of control, hierarchy, and physical place, the values of the V tower will be more in tune with the de-territorialized and fluid dynamics of the twenty-first century. As the center of gravity in the international system migrates away from states, innovative, even radical, approaches to representation and communication will have to be identified and implemented if governments are to stay on as players in an ever-changing game. A shift towards virtual platforms, as represented by the construction of a V Tower or something like it, represents barely a start. But it may be, at least, that.

ABSTRACT: This essay reviews the early work of the U.S. Information Agency (1953–1999) in the field of computer and on-line communications, noting the compatibility of a networking approach to USIA's institutional culture. The essay then traces the story forward into the work of the units within the U.S. Department of State which took over public diplomacy functions in 1999. The article argues that this transition deserves a large part of the blame for the difficulty which the risk-averse State Department displayed in embracing first the web and then the full range of qualities associated with Web 2.0. The essay also notes the challenge of a non-diplomatic agency—the Department of Defense—playing a dominant role in digital and other forms of outreach at some points in the process. The essay ends by noting the recent evolution of the State Department's approach to digital media and the emergence of a non-governmental model for American digital outreach (known by the acronym SAGE) which may overcome many of the institutional limits experienced thus far and provide a way to bring together the relational priorities of the New Public Diplomacy with the relational capacities of Web 2.0 technology.

ABSTRACT: “Twiplomacy” is the title of a convention that took place in Turin, hosting among others Alec Ross, the social media strategist for the U.S. Secretary of State, and the Tunisian blogger Lina Ben Mhenni, who played a key role during the popular rise against Ben Ali. But more than a convention, digital diplomacy is a relevant change in the way embassies, movements and institutions spread information in real time, turning into powerful news-hubs. This is an adjustment that is largely due to the new needs related to the digital democracy that marks our age of digital communication, such as transparency and effectiveness.

ABSTRACT: Understanding, planning, engagement and advocacy are core concepts of public diplomacy. They are not unique to the American experience. There is, however, an American public diplomacy modus operandi with enduring characteristics that are rooted in the nation’s history and political culture. These include episodic resolve correlated with war and surges of zeal, systemic trade-offs in American politics, competitive practitioner communities and powerful civil society actors, and late adoption of communication technologies. This article examines these concepts and characteristics in the context of U.S. President Barack Obama’s strategy of global public engagement. It argues that as U.S. public diplomacy becomes a multi-stakeholder instrument and central to diplomatic practice, its institutions, methods and priorities require transformation rather than adaptation. The article explores three illustrative issues: a culture of understanding; social media; and multiple diplomatic actors. It concludes that the characteristics shaping the U.S. public diplomacy continue to place significant constraints on its capacity for transformational change.

ABSTRACT: This paper focuses on the phenomenon of digital diplomacy, critically analyzed from the perspective of philosophical psychoanalysis. The study aims to elaborate the theoretical underpinnings of digital diplomacy through employing the conceptual framework of collective individuation and psycho-technologies developed by French critical philosopher Bernard Stiegler. Stiegler’s philosophical conception of contemporary politics under the condition of globalized cultural and economic capitalism is employed in this work to explain the dramatic changes in diplomatic relations taking place on the international arena at the beginning of the new century.

Hallams, E. (2010). Digital Diplomacy: The Internet, the Battle for Ideas & U.S. Foreign Policy. CEU Political Science Journal, 4, 538-574.

ABSTRACT: This paper explores how the Internet and new media technologies are playing a growing role in transforming U.S. public diplomacy programs, as part of broader efforts to counter the “Grand Narrative” of radical Islamic extremism. The Internet is at the heart of “digital diplomacy,” communicating ideas, promoting policies and fostering debate and discussion aimed at undermining support for Al-Qaeda and crafting a credible alternative narrative. Programs such as Public Diplomacy 2.0 are becoming increasingly important as the U.S. seeks both to revitalize its tools of soft power and reach out and engage the “youth generation” of the Muslim world. The paper examines the way in which Al-Qaeda has created a virtual battle space that is growing in importance as Western military forces seek to dominate the physical battle space. It explores how U.S. policymakers have begun to grasp the importance of fusing soft power, public diplomacy and information strategies, an approach at the heart of the technologically-savvy Obama Administration.

Hayden, C. (2012). Social Media at State: Power, Practice, and Conceptual Limits for U.S. Public Diplomacy. Global Media Journal-American Edition, 11(21), 1-20.

ABSTRACT: Social media technologies represent a significant development for U.S. public diplomacy: both in practice and in conceptualization. This article analyzes policy discourse regarding social media's role in U.S. public diplomacy to characterize conceptual development of U.S. public diplomacy practice. It critically assesses U.S. strategic arguments for technology and public diplomacy, the relation of public diplomacy to traditional diplomacy after the so-called “public diplomacy 2.0” turn, and how the collaborative potential of these developments complicate the utility of soft power to justify public diplomacy.

ABSTRACT: Nation-state efforts to account for the shift in the global communication environment, such as “public diplomacy 2.0,” appear to reflect inter-related transformations – how information and communication technologies (ICTs) change the instruments of statecraft and, importantly, how communication interventions serve as strategically significant foreign policy objectives in their own right. This paper examines two cases of foreign policy rhetoric that reveal ways in which the social and political role of ICTs is articulated as part of international influence objectives: the case of “public diplomacy 2.0” programs in the United States and Venezuela’s Telesur international broadcasting effort. These provide evidence of the increasing centrality of ICTs to policy concerns and demonstrate how policy makers translate contextualized ideas of communication effects and mediated politics into practical formulations.

ABSTRACT: The elections of President Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012 provided pivotal moments in U.S. relations with foreign publics. Examining the kind of communication cultivated between public diplomacy practitioners and publics, this article focuses on social media discourse about the 2012 U.S. election posted to U.S. diplomacy efforts on Facebook. We analyze information generated by U.S. embassy sites in Bangladesh, Egypt, and Pakistan to understand the qualities of the communication engendered by these public diplomacy overtures, the nature of public argument via the media platform, and how the election served as a process to further contemporary U.S. public diplomacy. We found that the discussion that took place in response to the announcement of Obama’s reelection did not resemble a deliberative forum for debating U.S. foreign policy or regional implications. Rather, much of the messaging on these sites constituted what we term “spreadable epideictic.” Implications are charted for research and practice.

ABSTRACT: This introductory essay highlights the key findings, methodological tool kit, and production process of this Special Issue. We argue that communication researchers are uniquely positioned to analyze the relationships between social media and political change in careful and nuanced ways, in terms of both causes and consequences. Finally, we offer a working definition of social media, based on the diverse and considered uses of the term by the contributors to the collection. Social media consists of (a) the information infrastructure and tools used to produce and distribute content that has individual value but reflects shared values; (b) the content that takes the digital form of personal messages, news, ideas, that becomes cultural products; and (c) the people, organizations, and industries that produce and consume both the tools and the content.

ABSTRACT: The internet is enabling new approaches to public diplomacy. The U.S. Digital Outreach Team (DOT) is one such initiative, aiming to engage directly with citizens in the Middle East by posting messages about U.S. foreign policy on internet forums. This case study assesses the DOT's work. Does this method provide a promising move towards a more interactive and individualized approach to connecting with the Middle East? What are the strategic challenges faced by "public diplomacy 2.0?"

ABSTRACT: In the final quarter of 2010, public diplomacy and traditional diplomacy were often at the forefront of news stories in the media. Referred to as Cablegate, the biggest story for traditional diplomacy was the decision by online media source, WikiLeaks, to post tens of thousands of U.S. diplomatic cables to its website.

Lengel, L., & Newsome, V. A. (2012). Framing Messages of Democracy through Social Media: Public Diplomacy 2.0, Gender, and the Middle East and North Africa. Global Media Journal, 11(21), 1-18.

ABSTRACT: This study examines how U.S. public diplomacy directed toward the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and public diplomacy from the MENA to other regions, including the U.S., uses social media. It analyzes how messages regarding recent events in the MENA are constructed for Western audiences, how public diplomacy rises from this construction, and the resulting the benefits and challenges within intercultural communication practice. Utilizing a framework for social media flow the processes of gatekeeping are examined, from both state and non-state actors representing MENA voices, and western actors who receive those voices, to illustrate public diplomacy from the MENA is a “glocal” construct of the traditions of both of those localities.

Metzgar, E. T. (2012). The Medium is Not the Message: Social Media, American Public Diplomacy & Iran. Global Media Journal-American Edition, 11(21), 1-16.

ABSTRACT: This article discusses communication concepts associated with the practice of public diplomacy 2.0, applying those concepts to analysis of American implementation of PD 2.0 directed toward Iran. Although interaction between the United States and the Iranian people may be limited, may not always take place in real time, and certainly cannot serve as a substitute for the interactions facilitated by a bricks-and-mortar embassy on the ground, the Virtual Embassy Tehran and its social media accouterments represent an interesting application of American public diplomacy priorities. The effort is consistent not only with the goals of 21st Century Statecraft, but also with the Administration’s stated preference for engagement while still pursuing vigorous economic sanctions toward the Iranian regime. The effort also has potent symbolic value given the United States’ promotion of global internet freedom as a foreign policy goal.

ABSTRACT: In 2010 the U.S. State Department funded an “Apps4Africa” contest to encourage development of socially conscious mobile applications for Africa. The initiative marked a significant departure from traditional public diplomacy efforts to expand diplomatic outreach beyond traditional government-to-government relationships. This case study analyses Apps4Africa to reveal its appropriateness as a model for future efforts and concludes Apps4Africa succeeded primarily because it responded to the changing dynamics of the 21st Century.

ABSTRACT: States articulate their identity and foreign policy interests in the international system, seeking to influence the perceptions of others and to create an environment in which their goals and efficacy as an actor are viewed as legitimate. In the age of mass communication technologies and new media, the public diplomacy initiatives utilized to communicate these narratives have gone digital. This article studies how India has utilized this new media environment for its public diplomacy and argues that digital diplomacy should be conceptualized as a larger set of practices that form an integral part of diplomacy itself: to communicate foreign policy goals and decisions, construct a strategic narrative of Indian foreign policy and counter narratives inimical to Indian interests.

ABSTRACT: This article examines how South Korean and Japanese public diplomacy organizations employ digital media to embrace the principle of ‘networked public diplomacy’ through analyses of the web and social media practices. The results of content analysis suggest that both South Korea and Japanese public diplomats focused on promoting their cultural products and national values through their use of texts and visual images. In addition, user profile analysis gaged the degree of users' engagement in the organizations' profiles and identified the demographic features of users. Comparative data suggest the Korean public diplomacy organization was more successful at attracting and engaging with foreign public than the Japanese public diplomacy organization. These results imply that although these two countries had similar sociopolitical backgrounds and perspectives of public diplomacy, they had distinct forms of internal information networks, communication strategies, and social networking performances with public.

ABSTRACT: Rapid advancements in communication and transportation technologies in recent history have created new and emerging tools that make it possible for every individual to share information with a global audience. Social networking technologies, especially, have revolutionized the possibilities of person-to-person communication, particularly by making obsolete the geographical boundaries that once divided cultures and nationalities. Diplomacy, an international relations activity traditionally claimed as the domain of the nation-state, has become more accessible to ‘ordinary’ citizens and advocacy groups and is taking new forms as individuals and groups initiate grassroots public diplomacy activities. This paper presents the case studies of two such initiatives—Turkayfe.org and the Rediscover Rosarito Project—that have successfully implemented new communications technologies and Web 2.0 strategies in their international outreach campaigns.

ABSTRACT: Technology matters but do not neglect the importance of people. Hierarchies can collapse and unpredictable actors may emerge, particularly during crisis. Amidst information, misinformation and disinformation, trust is the most highly prized commodity. Social media literacy is a new, crucial component of diplomacy. Diplomatic structures must adapt to stay relevant.

ABSTRACT: We live in an era of pervasive connectivity. At an astonishing pace, much of the world’s population is joining a common network. The proliferation of communications and information technology creates very significant changes for statecraft. But we have to keep in mind that the Internet is not a magic potion for political and social progress. Technology by itself is agnostic. It simply amplifies the existing sociologies on the ground, for good or ill. And it is much better at organizing protest movements than organizing institutions to support new governments in place of those that have been toppled. Diplomacy in the twenty-first century must grapple with both the potential and the limits of technology in foreign policy, and respond to the disruptions that it causes in international relations.

ABSTRACT: This paper specifies two main areas in which diplomacy is changing as a result of evolving social patterns. First, we look at the relationship between representation and governance: if anything, diplomatic work is traditionally about representing a polity vis-à-vis a recognized other. To the extent that such representation now increasingly includes partaking in governing, however, a whole array of questions about the relationship between diplomats and other actors emerges. Most prominently, are the governing and representing functions compatible in practice, or do they contain inherent tensions? Second, we focus on the territorial-nonterritorial character of the relation between the actors who perform diplomatic work and the constituencies on whose behalf they act and from which they claim authority. Building on these distinctions, contributors to this issue use their empirical findings to reflect not only on the evolution of diplomacy, but also on broader debates on the changes in world politics.

ABSTRACT: study identifies perspectives of relationships publics have about countries other than their own and examines whether publics engaged through social media-based public diplomacy programs demonstrate different relationship perspectives. Q methodology and survey research were used to investigate these issues. Data come from South Korean adult internet users, including members of Café USA, an online community run by the U.S. Embassy in Seoul. Three relationship perspectives were identified: outcome-based, sincerity-based, and access-based. Compared with other groups, Café USA members put more emphasis on sincerity in their relationships with the United States. The results of this study indicate that individuals’ subjectivity should be considered as far more contextualized and nuanced than has been the case in previous research on national image or country reputation.

Slaughter, A. (2009). America's Edge: Power in the Networked Century. Foreign Affairs, 94-113.

ABSTRACT: In a networked world, the United States has the potential to be the most connected country; it will also be connected to other power centers that are themselves widely connected. If it pursues the right policies, the United States has the capacity and the cultural capital to reinvent itself. It need not see itself as locked in a global struggle with other great powers; rather, it should view itself as a central player in an integrated world. In the twenty-first century, the United States' exceptional capacity for connection, rather than splendid isolation or hegemonic domination, will renew its power and restore its global purpose.

ABSTRACT: This exploratory study examines national governments’ increasing information dependencies on non-state actors. The impact of new government information partnerships afford non-state actors with a more influential role in diplomatic processes. Using the U.S. Department of State as the case study, this work synthesizes literature on the nature, functions, and information assets involved in diplomacy to explicate how digital government is changing state and non-state communicative dynamics and influences.

Vanc, A. (2012). Post-9/11 U.S. Public Diplomacy in Eastern Europe: Dialogue via New Technologies or Face-to-Face Communication? Global Media Journal-American Edition, 11(21).

ABSTRACT: Has the fabric of communication between the United States and the countries once behind the Iron Curtain changed from simply delivering messages through international broadcasters to collaborative relationships built on dialogue? This work seeks to discern whether diplomats have embraced and applied dialogic principles with foreign publics by examining how U.S. diplomats engage with foreign publics and what tools they use to engage in dialogue. Interviews with U.S. diplomats in Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia show that U.S. diplomats embraced and applied dialogic principles, and employed dialogue to establish long-term collaborative relations with people abroad. Communicating with foreign publics in transitional societies required a multifaceted approach that required a variety of communication tools, among which the prevailing preference was for face-to-face communication.

Williamson, W. F., & Kelley, J. R. (2012). # Kelleypd: Public Diplomacy 2.0 Classroom. Global Media Journal-American Edition, 11(21), 1-19.

ABSTRACT: This paper looks at innovative strategies for how to effectively teach Public Diplomacy by integrating technology into the classroom. The results are based on a Foundations of Public Diplomacy class taught at American University in Spring 2012. The course explored recent shifts in public diplomacy toward virtual statecraft. As part of this focus, the syllabus integrated an ongoing social media dimension over the duration of the course. From the beginning, the course had a dedicated Twitter hashtag (#kelleypd) that gained traction and became part of the larger dialogue around the topic of public diplomacy. The second half of the class featured student presentations, which were required to include technology components. The results from the class showed a high level of participation and interaction within the class and into the larger community. In addition, the students gained skills in media creation that helped them to understand which tools would be appropriate in diverse situations.

ABSTRACT: This article examines the role of social media in public diplomacy. Using the cases of the Iranian riots and the Xinjiang riots in 2009, the article investigates the emerging strategic implications of social media such as Twitter, Facebook and YouTube in national and international politics. The research identifies web-based public diplomacy as an increasingly important trend in foreign policy strategies. This strategic asset is based on technology-enabled word-of-mouth communication, implemented through social media, facilitated by anonymous proxy. An inadvertent result of web-based public diplomacy is the creation of ‘smart mobs’, a consequence that may be intentionally used by groups with certain political agendas. Finally, the article recommends that China utilize the full potential of social media to achieve its public diplomacy goals and to enhance its global agenda-setting power.

Zaharna, R. S., & Rugh, W. A. (2012). Issue Theme: The Use of Social Media in U.S. Public Diplomacy. Global Media Journal-American Edition, 11(21), 1-8.

ABSTRACT: The rise of social media is revolutionizing how state and non-state actors communicate with publics in the international community. While governments across the globe are scrambling to adjust, U.S. public diplomacy has emerged as a clear leader in the field according to a new report (Hanson 2012). This special issue explores the various dimensions of the use and impact of social media on U.S. public diplomacy and the public diplomacy of other state and non-state actors directed at the U.S. public.

ABSTRACT: This research proposed that social media use in public diplomacy should first be a strategic issue management (SIM) process. Using two case studies, the research identified four phases of the SIM process, namely the issue fermenting and going viral phase, the proactive phase, the reactive phase, and the issue receding and new issue fermenting phase. Social media are largely tactical tools in the first and the last phases. But they may become strategic tools in the proactive and reactive phases, in which diplomats may use them to reinforce a favorable viral trend, to build an agenda, and to respond to a conflict. In addition, the SIM approach argues that engagement, the Obama administration’s diplomatic doctrine, should be reassessed in a mixed-motive framework instead of being narrowly equated to dialogue.

ABSTRACT: With the evolution of communication technologies, traditional public diplomacy is transforming. This study examines the practice of the U.S. Embassy's public diplomatic communication via social media, namely Chinese mainstream blogging and micro-blogging, sites using Tencent for a case study. This study analyzes the embassy's blog and micro-blog entries and an interview with the embassy's public diplomacy officer. Based on the content analysis and interview, this study discerns the key features of the U.S. Embassy's public diplomatic communication using social media and further suggests that the common values and interests related to the global public as well as experience-sharing and relationship-building might become the focus of new public diplomacy research.

Reports on Digital Diplomacy

Burson-Marsteller. (2014). Twiplomacy Study 2014. Twiplomacy.

ABOUT: This is an annual study that looks at the global use of Twitter by world leaders as they exercise Digital Diplomacy. According to this study, more than half of the world’s foreign ministers from every region of the world and their institutions are active on Twitter. The report discusses how Twitter is fostering "virtual diplomatic networks" as well as social marketing campaigns that rely heavily on Hashtag Diplomacy. The most 'followed' global leaders who have a strong presence on Twitter and the "most active accounts" are also highlighted in the report. Pope Francis is identified as the "most influential tweep" and Spanish as the "most tweeted language." The report shows that diplomats are exploring new technologies and social media platforms such as Twitter as they design their digital diplomacy strategies and redefine their 21st century statecraft.

ABOUT: Can Facebook and Twitter change the world? Can all the nifty new social-networking sites promote democracy and a better understanding of American values around the world? The potential is certainly there—as was seen in the invaluable Twitter updates during the post-election protests in Iran. The U.S. government is embracing Web 2.0 for an ambitious strategy of reaching previously untapped populations around the world—calls it Public Diplomacy 2.0. While the potential progress is undeniable, so is the potential danger. Public diplomacy expert Helle Dale explains the recent developments, strategies, benefits, and risks of cyber diplomacy.

Fontaine, R., & Rogers, W. (2011). Internet Freedom: A Foreign Policy Imperative in the Digital Age. Center for a New American Security.

ABOUT: The U.S. government must develop a truly comprehensive Internet freedom strategy. Over the past several years, it has taken important, positive steps in a number of areas, from providing technologies to shaping norms to engaging the private sector. It must now build on these efforts to integrate other elements, including trade policy, export control reform and others. Underlying all these efforts is a bet – essentially the same bet that the United States placed during the Cold War – that supporting access to information and encouraging the free exchange of ideas is good for America.

ABOUT: This report examines the transformational changes in diplomacy’s 21st century context: permeable borders and power diffusion, new diplomatic actors and issues, digital technologies and social media, and whole of government diplomacy. It critically assesses implications for diplomatic roles and risks, foreign ministries and diplomatic missions, and strategic planning. In an attempt to bridge scholarship and practice, the report explores operational and architectural consequences for diplomacy in a world that is more transparent, informal, and complex.

Hanson, F. (2011). The New Public Diplomacy. Lowy Institute for International Policy.

ABOUT: E-diplomacy is not a boutique extra for foreign ministries and increasingly will be central to how they operate in the 21st century. Digital platforms will require cultural change, but they also promise a wide range of benefits, whether that is taking a much more active role in managing their public diplomacy messages or engaging audiences that were previously out of reach.

ABOUT: This report argues that one of the biggest challenges for foreign ministries is adaption to a new environment in which new technologies need to be integrated into diplomacy. State is at the vanguard of this compared to other MFAs. It describes the history of eDiplomacy at State, three of its main foci (public diplomacy, internet freedom and knowledge management) and gives recommendations for other foreign ministries. These recommendations include paying more attention to social media, cooperation with like-minded states on issues of internet freedom and learning from State in terms of knowledge management. Areas in which State could improve are consular affairs, disaster response, diaspora engagement, engagement with external actors, coordination with partner governments and, from a whole of government perspective, policy planning.

Hanson, F. (2012). Baked in and Wired: Ediplomacy@ State. Foreign Policy at Brookings.

ABOUT: This article suggests ediplomacy efforts at State can be structured around eight different work programs. Using this conceptual framework, Public Diplomacy is currently the largest component of this ediplomacy effort if measured in human resources terms, although more money is probably spent on Internet Freedom, with much of the work in this space outsourced. The eight work program model, also suggests areas where future ediplomacy work could be amplified, with Policy Planning and Disaster Response, surely high priority areas. For other foreign ministries that have been concerned about developing the theory before they get to the doing, the message is clear. Ediplomacy has arrived. The choice for them is to either embrace the opportunities and advantages ediplomacy presents or to be passive and be shaped (and sidelined) by this latest technological revolution.

ABOUT: RAND researchers conducted an assessment of the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, Labor (DRL) Internet freedom portfolio for Fiscal Year 2012-13. Applying an analytical methodology employing both multi-attribute utility analysis and portfolio analysis techniques, the assessment showed good alignment between State’s strategy and the accumulative effect of the eighteen funded projects. Additionally, the portfolio was assessed to be well balanced with an unrealized potential for supporting emergent State Department needs in enlarging political space within authoritarian regimes. We found that the investment in developing Internet freedom capacity and capabilities would likely have residual value beyond the portfolio’s funded lifespan, with positive, but indirect, connections to civic freedom. Moreover, promoting Internet freedom appears to be a cost-imposing strategy that simultaneously aligns well with both U.S. values and interests, pressuring authoritarian rivals to either accept a free and open Internet or devote additional security resources to control or repress Internet activities. Finally, it was assessed that the value of such analysis is best realized over multiple stages of the portfolio’s lifecycle.

ABOUT: The Clingendael Institute was commissioned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Finland to write this report which discusses the changing environment of diplomacy in terms of four key dimensions of what is termed integrative diplomacy: contexts and locations, rules and norms, communication patterns and actors and roles. It explores the consequences of this changing diplomatic environment for the processes and structures of diplomacy, particularly ministries of foreign affairs. The report is one output from a larger and developing international project on Futures for Diplomacy.

ABOUT: This report emanates from the second annual Aspen Institute Dialogue on Diplomacy and Technology. The Dialogue addresses ways that diplomacy can and should incorporate new information and communications technologies (ICT) in the days and years ahead. Given the social, many-to-many nature of these new technologies, it naturally focuses on public and citizen diplomacy, though not exclusively. In the first year, the Dialogue explored how technology has changed the nature of diplomacy in all its facets: traditional, public, citizen, cultural and business diplomacies.

ABOUT: For nearly all of the Bush administration, America’s standing in most parts of the world remained dismally low. The reputation it left behind after 2008 stood ready for a dramatic overhaul with the arrival of the popular Barack Obama. Beginning almost immediately with a positive new message offered to the Muslim world, Obama’s public diplomacy is decidedly less notable for its substantive achievements than the strides he and Secretary Hillary Clinton have made in modernizing the means of public diplomatic discourse. During its time in office the Obama administration has worked to broaden and accelerate communications with audiences abroad by inserting social media and technology exchanges into the toolkit of the public diplomat. Yet the administration’s tendency toward strategic incoherence means public diplomacy strategy remains a mystery. As the content of public diplomacy falls behind innovations in methods to deliver it, one has to wonder: what is the world hearing?

Lane, N. F., & Matthews, K. R. (2013). 2013 Policy Recommendations for the Obama Administration. Baker Institute for Public Policy.

ABOUT: The key to Digital Diplomacy is a) the ability to shape a message quickly and adapt it as conditions change and b) to be able to actually engage in dialogue with the target audiences in the foreign country; two elements that have never before been possible. These two factors are very powerful. Governments that understand this and engage with a strategy will have an effective Soft Power tool.

ABOUT: This report is a result of the first annual Aspen Institute Dialogue on Diplomacy and Technology. The topic for this inaugural dialogue is how the diplomatic realm could better utilize new communications technologies. The group focused particularly on social media, but needed to differentiate among the various diplomacies in play in the current world, viz., formal state diplomacy, public diplomacy, citizen diplomacy and business diplomacy. Each presents its own array of opportunities as well as problems. In this first Dialogue, much of the time necessarily had to be used to define our terms and learn how technologies are currently being used in each case. To help us in that endeavor, we focused on the Middle East. While the resulting recommendations are therefore rather modest, they set up the series of dialogues to come in the years ahead. The technologies will change over time. What is important is that careful attention be paid in every generation to how they can best be used in the service of the ultimate goal of diplomacy: worldwide peace and stability. The means will change but the ends remain the same.

ABOUT: In this research the social media communication of the Finnish missions abroad is studied. The missions have implemented social media as a part of their communication mainly since 2010. It has been suggested that there is a need for re-evaluation of the theories of public relations due to the rise of social media. Therefore, in this thesis, the theories of dialogue are inspected closer. In addition, this research tested the applicability of the Communication Grid (van Ruler 2004) in the context of social media. The purpose is to offer some guidelines about social media communication in the context of public diplomacy.

Sandre, A. (2013). Twitter for Diplomats. ISSUU.

ABOUT: This is the first publication in a series designed to analyze how social media diplomacy helps create – and maintain – a true conversation between policymakers and citizens, between diplomats and foreign public. The book is not a technical manual, or a list of what to do and not to do. It is rather a collection of information, anecdotes, and experiences. It recounts episodes involving foreign ministers and ambassadors, as well as their ways of interacting with the tool and exploring its great potential. It aims to inspire ambassadors and diplomats to open and nurture their Twitter accounts – and to inspire all of us to use Twitter to better listen and open our minds.

ABOUT: This report explores public diplomacy 2.0 for the Royal Embassy of the Netherlands and its various Consulates in the United States. Public diplomacy 2.0 includes a government’s presence on social media, such as Facebook, Twitter and blogs. In 2010, the Royal Embassy of the Netherlands in Washington, D.C. and the Consulate General of the Netherlands in San Francisco, have prioritized digitalization and engagement on social media. Adding to the ongoing development and implementation of the social media strategy by the Department of Public Diplomacy, Press and Culture, a meta research on public diplomacy 2.0 was conducted. This paper explores the structure, organization, objectives, audience, regulation and evaluation of effective web 2.0 practices. Social media asks for a hybridization of open and closed communication practices.

Dissertations and Theses on Digital Diplomacy

ABSTRACT: The aim of this thesis is to investigate how American power is adapting to a changing post-Cold War global landscape. It is commonly accepted that many of the most visible cultural expressions of globalization are American. However, contemporary accounts have proven inadequate in assessing how such forces have helped provide the infrastructure for America’s global dominance. With growing debate over the decline of American influence, the thesis intends to address how American statecraft is attempting to redefine itself for a digital age.

ABSTRACT: This paper will build upon recent work that views diplomacy broadly as, among othings, a form of change management in the international system. Change is conceptualized here in two basic forms, top-down exogenous shocks and bottom-up incremental shifting. Diplomacy helps to manage both sources of change, though there is variation in process and tool effectiveness depending on the type of change that states are actively managing e-Diplomacy is defined as a strategy of managing change through digital tools and virtual collaboration.

ABSTRACT: This paper set out to gain insight into the ways Germany and Sweden conduct their public diplomacy on Twitter. It explored the ways in which the organizational structure influences the states’ conduct in social media and shed light on the difficulties that arise when trying to adapt diplomacy to a communicative situation that is said to have changed dramatically. In an exploratory study, this thesis tried to answer the larger question whether and in what way Twitter can be of use to public diplomacy.

ABSTRACT: Social media not only proved to be a powerful medium in influencing the public but also drew the attention of public diplomacy professionals, observers, and political analysts on how it could be positively utilized to enhance a country's image. The research determines the tools used in adopting ICT to cultivate public diplomacy in Kenya, its impact and challenges, and analyzes the successes of adopting ICT into diplomacy in order to ensure efficiency in public participation of government policies and other processes. It adopts the Actor-Network Theory (ANT) as an explanatory framework of analysis. The research outlines its findings in terms of knowledge and expertise in adopting E-diplomacy in Kenya and lays out strategies in curbing challenges such as cybercrime which are inter-twined with ICT.

ABSTRACT: In recent years, there were many conflicts between the United States and China in cyberspace. As shown by Secretary of State Clinton’s “Internet Freedom” speeches, “Blog Briefing” and Google’s withdrawal from China’s market, one can easily draw the conclusion that the Internet has already grown up to an important strategic space for the United States to implement diplomatic strategy. Internet diplomacy became a significant approach to supplement the traditional diplomatic modes in the process of the U.S. diplomacy on China.

ABSTRACT: This thesis argues that extended use of the Internet not only poses challenges, but also new possibilities for diplomatic actors in the European Union, especially those of small states. The study aims at the creation of a nexus between a lack of ‘traditional’ diplomatic capacities, as shown by tangible diplomatic infrastructure, and an increased use of public diplomacy in cyberspace, or ‘e-diplomacy’. The hypothesis holds that small states pursue higher efforts to leave a larger `digital diplomatic footprint' in social media, aiming at a projection of a positive image inside the public sphere.

Blogs and Essays on Digital Diplomacy

Ardaiolo, M. (2014, March 6). We’ve Upgraded to Public Diplomacy 2.1, But Does it Matter? CPD Blog.

Berthold, A. (2010, June 1). New Technology and New Public Diplomacy. PD Magazine.

Burson-Marsteller. (2012, August 2). Is 'Twiplomacy' Replacing Traditional Diplomacy? TMCnet.

Dupont, S. (2010, August 3). Digital Diplomacy. Foreign Policy.

Hanson, F. (2012, October 29). Ediplomacy: The Revolution Continues. Lowy Interpreter.

Hanson, F. (2012, October 31). DFAT Should Embrace the Digital Age. Lowy Interpreter.

Horton, T. (2011, July 20). New Technology and New Public Diplomacy. PD Magazine.

Hughes, S. (2013, May 24). Digital Diplomacy: Here to Stay and Worth the Risk? BBC.

Kerry, J. (2013, May 6). Digital Diplomacy: Adapting Our Diplomatic Engagement. DipNote.

Kraus, E. (2013, August 1). Diplomacy in a Digitally Infused World. Diplomatic Courier.

Leach, J. (2013, July 19). Digital Diplomacy: Facing a Future Without Borders. Independent Voices.

Levinson, P. (2012, September 13). Everyone is a Diplomat in the Digital Age. PD Magazine.

Lichtenstein, J. (2010, July 16). Digital Diplomacy. The New York Times Magazine.

Manfredi, J.L. (2014, April 2). Hacking Diplomacy. CPD Blog.

Manor, I. (2014, May 11). The Social Network of Foreign Ministries. Exploring Digital Diplomacy.

Morozov, E. (2009, June 9). The Future of “Public Diplomacy 2.0.” Foreign Policy.

Sandre, A. (2013, November 11). 'Fast Diplomacy': The Future of Foreign Policy? The World Post.

Sandre, A. (2014, January 15). Diplomacy 3.0 Starts in Stockholm. The Huffington Post.

Seib, P. (2012, October 17). Twiplomacy: Worth Praising, but with Caution. Canadian International Council – Canada's Hub for International Affairs.

U.S. Department of State. (n.d.) The “Internet Moment” in Foreign Policy. 21st Century Statecraft.

Multimedia Resources on Digital Diplomacy

"A Panel Discussion on Digital Diplomacy Hosted by the U.S. Foreign Press Center." (2014).

ABOUT: Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs Evan Ryan, Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of Public Affairs Douglas Frantz, and Coordinator for International Information Programs Macon Phillips discuss "Digital Diplomacy."

"Alec Ross on Twitter and Digital Diplomacy." (2013). BBC News.

ABOUT: Alec Ross, senior advisor for innovation to the former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, talks about digital diplomacy and the need for diplomats to learn how and why to use social media networks.

"A Conversation with Petrit Selimi." (2013).

ABOUT: Deputy Foreign Minister of the Republic of Kosovo, Petrit Selimi, who initiated the digital diplomacy strategy for the Republic of Kosovo, talks about digital diplomacy with James Barbour, Press Secretary and Head of Communications at the British Embassy.

"Current Trends in Digital Diplomacy: Diplomacy + Social Good." (2014).

ABOUT: Jed Shein, Digital Director at the Embassy of Israel, Sanna Kandgasharju, Press Counselor at the Embassy of Finland, and Haitham Mussawi, Digital Diplomacy Editor at the Embassy of United Arab Emirates discuss their various digital diplomacy strategies and approaches.

"Digital Diplomacy and Foreign Policy." (2014). Future Tense. [Audio podcast].

The Future Tense program hosts Ben Scott, one of the pioneers of America’s office of E-Diplomacy, who argues that digital diplomacy is far more than the likes of Twitter and Facebook. It’s about engaging with communities and ‘non-state players’ who now have a greater voice on international issues.

"Digital Diplomacy Series: Foreign Policy and Digital Engagement." (2014).

ABOUT: The Italian Embassy in Washington, D.C. partnered with Young Professionals in Foreign Policy (YPFP) to host a panel discussion: "Foreign Policy and the Future of Engagement." Digital Diplomacy is an important topic for the Millennials who are the next generation of foreign policy leaders. The video highlights messages from the panel about the role of new technology in connecting diplomats with foreign publics.

"Foreign Policy in Stereo | Digital Diplomacy Series at the Italian Embassy." (2014).

ABOUT: The Italian Embassy in Washington, D.C. hosted a conversation with Anne-Marie Slaughter and Kim Ghattas as part of the Embassy's Digital Diplomacy Series. The discussion focuses on how political leaders and foreign publics can engage and interact with each other and “listen” to the other through digital platforms.

"Future of Diplomacy, Digital Impact on Ancient Art: Diplomacy + SocialGood." (2014).

ABOUT: In this panel, Lewis Shepherd, Director of Microsoft Institute for Advanced Technologies in Governments, Erlingur Erlingsson, Counselor at the Embassy of Iceland, and Paul Lewis, Washington Correspondent for the Guardian discuss the opportunities that digital communication tools offer to diplomats to interact and engage with the public.

"StateDept: Leveraging Digital for Public Diplomacy." (2013).

ABOUT: This discussion with U.S.. State Department representatives from across public diplomacy bureaus focuses on how State is leveraging digital technologies to extend their reach and connections with foreign publics around the world.

"The Digital Ambassadors of 2020." (2013).

ABOUT: In this video, British Ambassador to Lebanon Tom Fletcher addresses Swedish diplomats at their annual conference in Stockholm August 28-29, 2013. He talks about the challenges and opportunities the social media offers modern day diplomats.

"Twiplomacy: Should Canada follow Hillary Clinton's lead?" (2012). The Current. [Audio podcast].

ABOUT: In this podcast, The Current hosts Matthias Lüfkens, Director of Digital Practice of Burnson-Marsteller across Europe, Middle-East and North Africa to discuss his new study about Twiplomacy and how world leaders use twitter. The focus of the talk is on Hillary Clinton’s approach to digital diplomacy in comparison with her Canadian counterparts.

ABOUT: In this video, Victoria Esser, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Digital Strategy from the U. S. Department of State, speaks about the State Department's use of social media which has three goals: to understand people and events more clearly; to share real-time information; and to engage people as a way of building relationships.

ABOUT: In this video H.E. Arturo Sarukhan, H.E. Harold Forsyth, Alec Ross, Sarah Wynn-Williams, Martha Boudreau, and Tom Carver discuss the statecraft of the new century and the changing role of diplomats in the era of hyper-connectivity.

The Public Diplomat. (2014). "Political Ambassadorships & Twiplomacy." [Audio podcast].

ABOUT: The PDcast is a weekly podcast featuring Jennifer Osias, Julia Watson, Adam Cyr, and Michael Ardaiolo discussing the trending public diplomacy topics. In the fifteenth episode of this podcast experts talk about political ambassadorships and the use of social media networks for political and diplomatic purposes.

The Public Diplomat. (2014). "U.S. Public Diplomacy in a Digital Context." [Audio podcast].

ABOUT: In this Podcast, Michael Ardaiolo from The Public Diplomat discusses the general state of U.S. public diplomacy and its shift toward a digital world with Dr. Craig Hayden.

To download the full Digital Diplomacy Bibliography, click here