Note from the CPD Blog Manager: This blog is part one of a two-part series. A universal exposition like the one currently unfolding in Milan on the theme of “Food: Feeding the planet, energy for life” can be too sprawling...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Looking for God at the Dubai Expo

Note from the CPD Blog Manager: This piece is the third of an occasional series by CPD Faculty Fellow Nicholas J. Cull considering the treatment of religion at World Expos over the past 12 years. Read the other installments here: "Looking for God at the Milan Expo (Part 1)," "Looking for God at the Milan Expo (Part 2)" and "Looking for God at the Shanghai Expo: Religion, Nation Branding and the Soft Power Showdown in China." Cull visited Expo 2020 Dubai with USC colleague and filmmaker Mina Chow (CPD Faculty Fellow) and Expo expert Beverly Payeff-Masey of the Masey Archives in New York City, whose observations have influenced this piece.

Expo 2020 Dubai was always going to have a religious subtext. The UAE’s bid to host the first Expo in the Middle East was closely tied to the country’s desire for a positive international image, including openness to other faiths. This is part of the Emirati brand: distinguishing the country from its neighbor Saudi Arabia. The result was an Expo in which things included and things left out both spoke powerfully. The pavilions created by the host acknowledged a religious culture at the foundation of the UAE but framed the future in terms of openness and inclusivity. The Women’s Pavilion featured female icons of achievement irrespective of national origin including Ruth Bader Ginsberg. There were other indications of Emirati tolerance: alcohol was readily available at bars and restaurants around the Expo. God was held in a diplomatic balance.

The UAE’s own national pavilion hit broad notes of inspiration rather than specific religious messages. The fabulous building—designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava in the shape of a falcon’s wings—included a religious pun. The oculus at the center of its curved roof reproduced the Expo logo (derived from a 4,000-year-old golden ring found during the excavation of an ancient trading post) while also evoking the rose windows familiar from European gothic cathedrals. The content of the pavilion featured universal messages from the UAE’s founders projected in English onto sand dunes. One read, “Unity is the way to strength, honor and the common good.” The combined effect of the building and the messaging was to underline both the UAE’s achievement and openness to contributions from outside and to do so in spectacular style.

Several national pavilions reflected religious inclusivity. The Vatican had a pavilion built around the shared notion of human fraternity based on the declaration signed by Pope Francis in the UAE in 2019. Still more impressively, as a result of the Abraham Accords of 2020, Israel also had a pavilion. Unlike the Vatican, Israel’s pavilion mostly played down religion. It mentioned the holy places only in passing during a cheesy quiz playing on a video wall in the waiting area before the main show. The pavilion’s messaging emphasized the potential for economic cooperation. The pavilion culminated in a video show in which a female host of mixed Arab-Israeli origin, filmed against a stunning beach backdrop, led the audience in song and dance to emphasize the universal ‘beat’ of life. It was the same message of shared humanity found at the Vatican but set to music, with attractive backing musicians.

More than past Expos, Dubai 2020 felt like a true meeting at a global crossroads. In many cultures, crossroads are a sacred place.

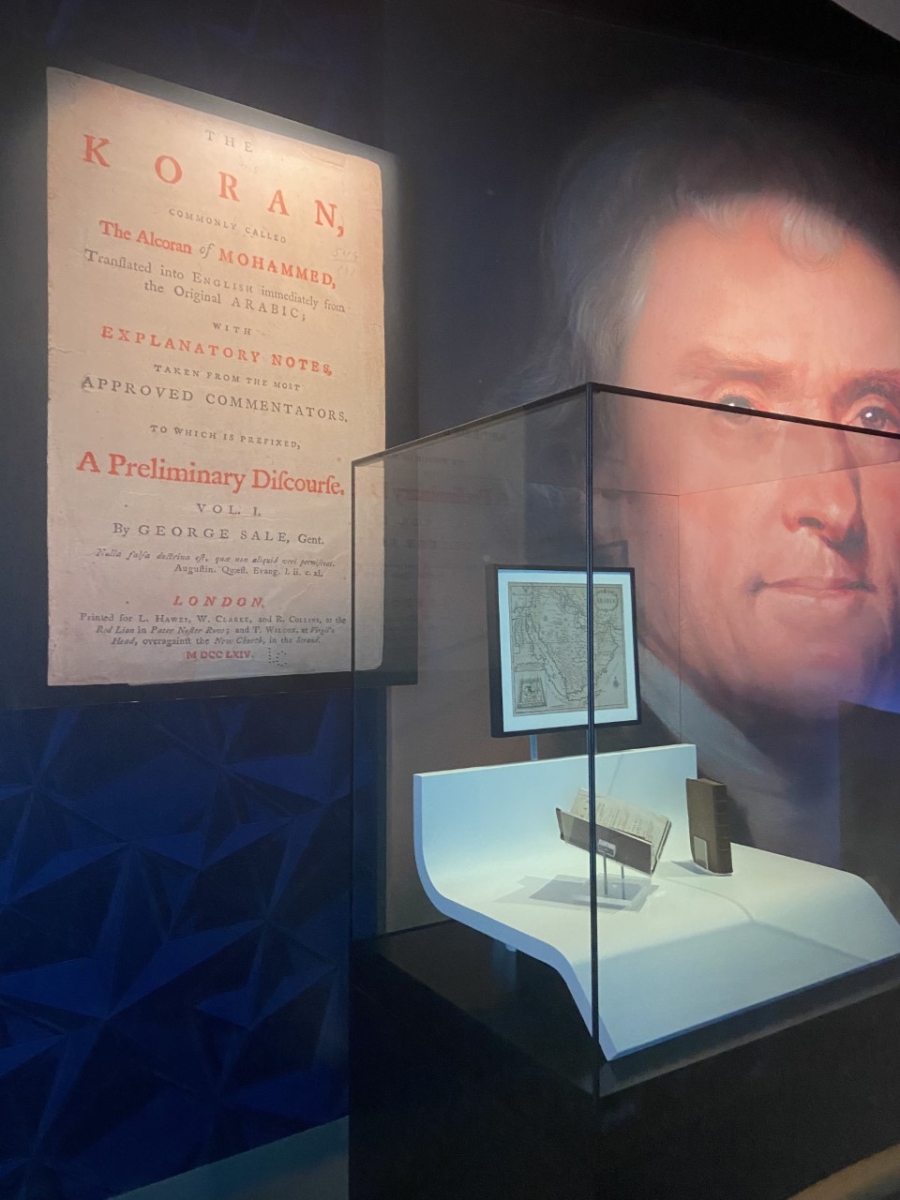

Some pavilions used religious themes to introduce themselves to Expo-goers. New Zealand, Australia and Peru rooted their self-presentation in the culture and religious practice of their original inhabitants. Armenia had sacred texts specific to its culture. The U.S. included a relic of value to both Americans and the people of the Middle East: a translation of the Quran once owned by Thomas Jefferson. The object had obvious impact on visitors, second only to the touchable piece of moon rock displayed in the pavilion’s space exhibit.

Some pavilions used religious themes to introduce themselves to Expo-goers. New Zealand, Australia and Peru rooted their self-presentation in the culture and religious practice of their original inhabitants. Armenia had sacred texts specific to its culture. The U.S. included a relic of value to both Americans and the people of the Middle East: a translation of the Quran once owned by Thomas Jefferson. The object had obvious impact on visitors, second only to the touchable piece of moon rock displayed in the pavilion’s space exhibit.

As around 90 percent people working in Dubai originate outside of the country, many national pavilions catered to diasporic groups, their own and those of others. India created an enormous pavilion clearly aimed at instilling diasporic pride. India’s religious heritage was central to the display, and the pavilion acknowledged the diversity of that heritage. Yet the pavilion felt a little too practiced: boxes ticked before visitors reached the floor were devoted to the virtues of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In contrast, there was something spontaneous and moving about Pakistan. Previous Pakistani pavilions have been disappointing. Its Dubai pavilion was not. Engaging inside and out, it included images of Pakistan's sites sacred to multiple faiths and laid claim to a broadly spiritual dimension to the country. Many pavilions included video walls with fabulous drone footage of spectacular countryside, but Pakistan’s take on the approach came across as genuinely inspiring and unexpected.

The Palestine pavilion wove religion into an impressive multilayered display based around the country’s sights, sounds, tastes, scents and textures. The touch area included an opportunity to touch a piece of aluminum from the dome of the rock and, a modern relic: a key symbolizing the right of Palestinians to return. This proved to be one of the few allusions to the conflict with Israel. While Israel’s Expo pavilion sought to move beyond the conflict, Palestine ignored it. Displays emphasized the presence of both Muslim and Christian heritage in Palestine but paid little attention to Jews or the state of Israel. The pavilion included images of Haifa, Caesarea and other places outside the boundaries of the Palestinian authority as Palestine, and the silhouette map of Palestine on display covered the pre-1948 territory. The display would doubtless prompt pride and nostalgia in the Palestinian diaspora in the UAE, but it is hard to imagine that simply denying the conflict and existence of Israel will encourage either the investors or visitors that the Palestinian territories need to move forward.

With an unresolved conflict fresh in my mind, I headed over to Ireland’s pavilion. As in Palestine, the Irish pavilion blurred a frontier, featuring elements from both the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland, however this was not a political statement made without consent but rather evidence of successful cross-border collaboration. Key partners in the pavilion included Tourism Ireland, the joint north-south tourism authority created in 1998. The pavilion video emphasized the Irish landscape and music rather than religious traditions, but there was a potent symbol of religious culture kept in the formal meeting area of the pavilion. In the meeting area stood two magnificent panels of stained glass: one in the shape of a cross, both depicting scenes of Northern Irish life and landscape. My guide explained that they were a gift created by former Loyalist (Protestant) extremists who, since the peace settlement, had devoted themselves to the art of stained glasswork. They had channeled community pride and religious identity into creativity. The gift had been made, received and displayed with love. It was a testament to how history can move on.

With an unresolved conflict fresh in my mind, I headed over to Ireland’s pavilion. As in Palestine, the Irish pavilion blurred a frontier, featuring elements from both the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland, however this was not a political statement made without consent but rather evidence of successful cross-border collaboration. Key partners in the pavilion included Tourism Ireland, the joint north-south tourism authority created in 1998. The pavilion video emphasized the Irish landscape and music rather than religious traditions, but there was a potent symbol of religious culture kept in the formal meeting area of the pavilion. In the meeting area stood two magnificent panels of stained glass: one in the shape of a cross, both depicting scenes of Northern Irish life and landscape. My guide explained that they were a gift created by former Loyalist (Protestant) extremists who, since the peace settlement, had devoted themselves to the art of stained glasswork. They had channeled community pride and religious identity into creativity. The gift had been made, received and displayed with love. It was a testament to how history can move on.

Expos are all about imagining a better future, but they always have their shadows, and Dubai 2020 was no exception. The UAE is not a democracy. Its image of tolerance coexists with tight media controls including repressive jail sentences for dissidents. The European Parliament requested a boycott of the Expo to admonish the UAE for its human rights record. The European Union did not have a pavilion and worked only through special events at the Expo. During the course of the Expo, some shadows lengthened. News agencies reported increased surveillance to ensure ‘safety,’ and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine cast a shadow over the final month. Yet despite such shadows, something remarkable had been achieved. Because of the astonishing diversity of Dubai’s work force, Expo 2020 felt like a coming together of the world, as when the Irish pavilion brought singers from 146 countries together as a global choir. More than past Expos, Dubai 2020 felt like a true meeting at a global crossroads. In many cultures, crossroads are a sacred place. A place to meet devils or angels. For six shining months, Expo 2020 gave the impression that even if both were in attendance, the angels may just have had the upper hand.

Photos:

Lead: The UAE Pavilion at Expo 2020 Dubai. Photo by by César Corona / Expomuseum.

Left: A translation of the Quran once owned by Thomas Jefferson on display at the USA Pavilion at Expo 2020 Dubai. Photo by Nicholas J. Cull.

Right: Panel of stained glass in the shape of a cross at the Ireland Pavilion at Expo 2020 Dubai. Photo by Nicholas J. Cull.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 28

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.