From scapegoating and vitriolic anti-immigrant rhetoric to loss of confidence in long-standing international institutions such as NATO, the United Nations and even the European Union, it seems that there is disturbing...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Islamic Art Now: Modern Islamic Art’s Powerful Cultural Diplomacy

When one thinks of Islamic art, there are a few images that initially come to mind. One is calligraphy; Arabic letters constructed in such a way that they create an animal or other complicated shape. Another is the geometrical perfection that is arabesque, using shapes to create intricate repeating patterns that adorn mosques and other buildings in the Islamic world.

When Islamic art is exhibited in museums, it is rarely ever displayed with modern pieces of art. Museums showcase pottery, ceramics, rugs, tile work, or giant Qur’ans delicately and beautifully written. It is the relics of the past that are center-stage at most art museums around the world. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), whose Islamic Art collection boasts an impressive 1,700 pieces, decided to ‘update’ the exhibit with modern pieces. Linda Komaroff, curator of Islamic Art and department head, acquired the museum’s first piece of “modern” Islamic art in 2006. The collection, "Islamic Art Now," has built on from then, and will occupy most of the fourth floor of LACMA until January 2016 (a second Islamic Art exhibit will be put in place after its removal). With 200 pieces, it is the largest collection of modern Islamic art in the world.

I went to the exhibit to experience art diplomacy firsthand. One of the first pieces to greet visitors after exiting the lift is the hum of neon lights; they are neon lights depicting Persian words. The words say “too khali,” which is Farsi for “void” or “empty.” Artist Arash Hanaei chose neon as the medium to create a metaphor for his hometown of Tehran, a city punctuated with neon lights, signs, and an emptiness created from the promise of a revolution that never fully came to fruition.

I continued my journey around the fourth floor and made note of the tone of the entire floor. It was quiet, dark, and rather eerie; it is as if you have been transported to a place that time has not yet touched, and yet every piece dripped with historical memories.

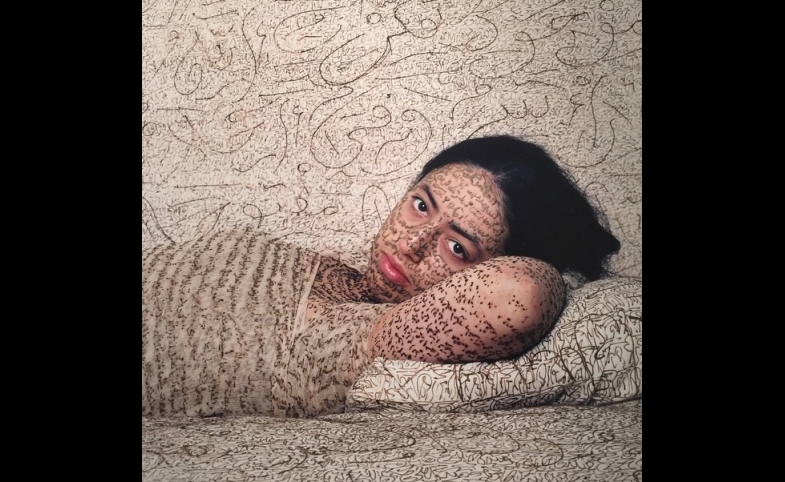

While I enjoyed all of the pieces, there were a couple that stood out to me as powerful pieces of cultural diplomacy from the Islamic World. The first is a massive, three panel photograph of a young woman entitled "Reclining Odalisque," created by Lalla Essaydi, an artist from Morocco. The subject is fully clothed, and every inch of her body is tattooed in Arabic script with traditional henna ink. She stares directly at her viewer, as if to challenge their voyeurism.

Instead of historical pieces, this exhibit displays work from artists who want to depict Islam as a dynamic, evolving religion that does not want to be solely defined by those who twist the religion like dogmatic calligraphy.

To me, this piece directly combated Orientalism. During the French Colonial occupation of Algeria, postcards were sent home of the “Other.” Malek Alloula, an Algerian author compiled these images in a book entitled, The Colonial Harem, that describes Algeria’s occupation by the French and how postcards of Algerian women were sent home to defend French rule. The women portrayed in those postcards were naked, caught off guard, inviting those viewing her to gaze longingly at her erotic pose. The French colonial rulers believed that if Algerian women were allowed to pose for such scandalous pictures, then Algeria was clearly in dire need of Western ministration. However, the Western viewer was unaware that these photographs were taken in studios with hired actresses, because the women of Algeria refused to remove their hijabs and abayas for photographers. These pieces of “art” were one component contributing to condescending stereotypes of Arab-Muslim women. This modern piece of art seeks to negate the impact of those postcards and other artwork of the Middle East in the 19th and 20th centuries. The subject of this artwork challenges the viewer with her piercing stare and clothed body as if to say, “I refuse to fit in the molds you once assigned to me.”

The next piece, "Between the motion/and the act/ Falls the Shadow" is a multimedia piece by Farideh Lashai, an Iranian artist. Behind heavy red curtains, the viewer finds themselves in a dark room. On parallel walls, video clips are playing. Between the video clips, there is a small café table with chairs. I took a seat and became a part of the art exhibit. When you sit, you are watching short clips from Iranian films, films created decades before the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The videos show Iranians in various nightclubs, smoking, drinking, women are uncovered, men are dressed in Western suits. They are watching a show; a show you also get to enjoy because it is being projected across from the nightclub scenes.

Various acts are performed, singers, belly dancers, and comedians take to the stage to entertain the nightclub guests. The viewer feels as if they are in the nightclub, laughing with their date, drinking, as their favorite performer takes the stage.

For a moment, it feels that this is the only Tehran that existed. I sat for ten minutes, enjoying the show and wondering if a waiter would ever bring me a shot of arak so that I could join in on the fun.

In recent years, Islam has been reduced to the destroyer of the Twin Towers, the blue of a burqa, or as the driving force behind extremist groups like Al Qaeda and most recently, ISIS. This exhibit offers viewers an escape from the “Islamic” images broadcast (narrowly) on network television and other media outlets.

The exhibit also breaks from the mold of typical museum Islamic art of ceramics, tiles, rugs, textiles and Qur’ans. It offers a glimpse of what some Muslim artists want to show the world about Islam. Instead of historical pieces, this exhibit displays work from artists who want to depict Islam as a dynamic, evolving religion that does not want to be solely defined by those who twist the religion like dogmatic calligraphy.

By using photographs, paintings, and multimedia pieces, previous subjects, such as women, are represented as multifaceted subjects, instead of as subjects of the Orientalist gaze. These pieces show sides of Islamic countries many Americans may never see. Many of the artists who contributed to this exhibit are women from the Arab/Muslim world. Although this is a minute detail in the scope of the entire exhibition, it gives women a space in art from the Islamic world, beyond being a subject of a piece. With so much negativity surrounding the Islamic world, the modern Islamic art exhibit at LACMA gives the viewer a positive glimpse of what the Islamic world actually is and allows the viewer to draw their own conclusions of what the Islamic world could become in the future.

Photo by Johanna/ CC by-SA 2.0

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

March 20

-

March 6

-

February 20

-

March 27

-

March 3

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.