The World Expo is arguably the single biggest showcasing event of a nation outside of its own borders. It is one of the few mass events that command worldwide attention. But unlike the Olympic Games or the FIFA World Cup,...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Expo Diplomacy 2020: Why the U.S. Needs to Go Back to the Future

As each wave of breaking news reminds us, the world is once again a dangerous place. International rivalry is back and the global institutions, alliances, values and the reputation of the United States all seem to be challenged. The current situation is not a rematch of the Cold War —our adversaries today have no special vision to advance beyond raw advantage. However, it would be foolhardy to proceed without paying attention to the lessons of the Cold War, especially as its outcome was favorable to U.S. interests.

While the overall strategy of U.S. foreign policy in the Cold War is well understood—building alliances, containing the adversary and waiting for the benefits of the U.S. approach to become self-evident—the tactics which dramatized the U.S. approach to the world have largely passed from public knowledge. Few remember that the world’s knowledge of the U.S. life and system was not spread solely by commercial communication channels but rather by the State Department and a Federal Agency—the United States Information Agency (USIA)—in partnership with key domestic stakeholders, including the education and creative sectors and U.S. corporations. USIA’s work included not only Voice of America radio and cultural outreach through educational exchanges, but periodic spectacular displays at international expositions, also known as World’s Fairs.

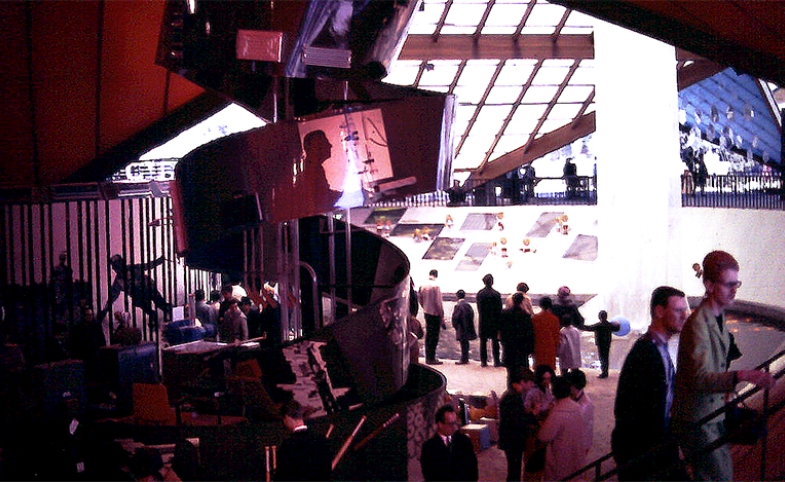

Cold War America told stories to the world at expo mega events like the Montreal Expo of 1967 or Osaka in 1970. Artifacts connected to the space program were particularly popular, but all manner of objects and glimpses of American life were part of the story of what one historian termed the “pavilions of plenty.” The U.S. even took the approach directly to the Soviet Union. A bilateral cultural treaty signed in 1958 cleared the way for the American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959 and the series of exhibits which toured that country for the remainder of the Soviet period. The touring shows presented in succession American innovations in fields like graphic design, transport and architecture, and culminated in the late 1980s with a show on information technology.

The exhibits worked by combining a number of the country’s strengths. The major exhibits were housed in signature pavilion buildings created by the greatest American architects of the age, including Buckminster Fuller. The contents were meticulously designed by experts with decades of experience engaging international audiences and a deep understanding of the materials they were presenting, like USIA expert Jack Masey. The pavilions or exhibits were staffed by young American guides who spoke the language of the venue country and whose friendliness, energy and openness carried a message in its own right. Finally, the whole thing was supported by the government back in Washington, through official statements, visits of presidents, vice presidents, celebrities and the scale of the investment inherent in presenting such contributions.

It offers a unique opportunity to connect not merely to the world of the present but to the rising generation whose impressions of the world are still forming. The expo organizers chose their theme of Connecting Minds; Creating the Future explicitly to engage young people craving culture and innovation.

To study what is now called American soft power in the field is to encounter thousands of stories of individual lives touched by personal experience of the U.S. at such exhibits: meetings with guides, the sight of a moon rock, a sample of Pepsi or an experience of an immersive film or photographic exhibit. The giveaways from these exhibits—button badges and such—have been treasured ever since. This was how public diplomacy was done. Why did it stop?

The agencies of U.S. soft power in the Cold War were victims of their own success. They billed themselves as necessities of the Cold War and logically headed the list for cuts when Congress began its search for a peace dividend and a balanced post-Cold War budget. USIA’s expo unit closed in the mid-1990s and the entire agency was merged into the State Department in 1999 with its agenda of global public engagement slipping back as a consequence. More subtly, the message within America’s “pavilions of plenty” was that the country’s great secret was the contribution of its private sector. In the post-Cold War period, U.S. pavilions were expected to be funded wholly by corporate sponsorship. Federal funding would require a special congressional appropriation, which no executive branch of the era felt willing or able to seek. The result of this was that while the tradition of international expositions flourished, U.S. participation declined—some fairs passed with damp squibs, others were skipped altogether. Some corporations with roots in the USA even resolved to distance themselves from the country and present their own exhibits in corporate zones at the fair.

Meanwhile, other countries understood that expositions remained relevant and invested heavily as hosts or as exhibitors. They moved into the expo business too and looked to fill the void left by the U.S. China joined the body which oversees expos—the Bureau of International Expositions or BIE—in 1993. By 2004 it was president and in 2010 its Shanghai Expo set new records for attendance and global participation. Expo stories have become rather predictable—usual suspects like France, Germany, the UK, Switzerland, Japan and South Korea place immense thought and carefully directed central resource into exquisitely designed spaces that communicate the essence of their national approach to the crowds. The hungry new-comers—China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Saudi Arabia—through immense resources rose into prestige projects that demand attention, while the U.S. fizzled.

There is frequently a moment of suspense over whether the U.S. will be represented. There is a moment of relief as corporate sponsors step up. There is a moment of disappointment as it proves impossible to match rivals on short notice. There is a coda of pride as student guides connect with actual audiences on the ground and a moment of surprise on the part of the U.S. public who had no idea that international expositions were still “a thing.” The outgoing Obama administration looked to break this cycle by re-establishing a permanent expo unit within the Department of State. The incoming Trump administration saw the logic of planning for expos and encouraged bids for the U.S. to host an expo in the future, including signing legislation in support of the effort. With this foundation we approach the expo of 2020 in Dubai.

The Dubai Expo is no ordinary event. Expo 2020 is a rite of passage for the UAE, much as hosting Osaka (1970) was for post-war Japan or Hannover for a reunified Germany (2000) or Shanghai (2010) was for rising China. The organizers envision 25 million visitors drawn not merely from the gulf but from the nations of South Asia and further afield for whom Dubai is a vital hub in international access. It is to be the first event of its kind in the Middle East or adjacent East Africa or South Asian regions. It offers a unique opportunity to connect not merely to the world of the present but to the rising generation whose impressions of the world are still forming. The expo organizers chose their theme of Connecting Minds; Creating the Future explicitly to engage young people craving culture and innovation.

For some countries a level success is already secured: British architects already have the signature buildings for their fair under their belts; designs from countries as small as Montenegro are receiving positive press. But the contribution of the U.S. remains unclear. There is no signature building in the works (the original partner for the pavilion was unable to raise funds for the project) and the whole treadmill of mediocrity or absence looms once more. But even as the ghost of expos past rattles his chains, a way forward is opening.

Visions of the future have the ability to reassure, to inspire, to rally and, maybe most importantly for our world right now, to wean humanity away from its most corrosive obsession: the past.

On July 29, U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo hosted a gathering of corporate dignitaries, expo experts and diplomats at the Department of State and called not only for support for a national effort in Dubai but also endorsed the concept of expos going forward. His vote of confidence was seconded by PepsiCo executive Mike Spanos (CEO for Asia, Middle East and North Africa), who reminded the audience of the enduring value to his brand of its partnership with the American exhibition in Moscow in 1959.

Yet it seems clear that just as a challenge is closer to that of the Cold War, so the response must be too, and—whatever the verdict on the experiment—the days of a wholly corporate-funded expo presence are gone. The financial aspects of the U.S. pavilion in Milan 2015 were a disaster; the U.S. pavilion’s architect has yet to be properly paid. The partner for the 2020 pavilion not only failed to raise enough money but has been investigated for influence pedaling. Any U.S. presence at Expo 2020 and going forward needs to be a true cross-sector partnership including a federal appropriation of funding. Hopefully the holders of the purse strings in the House and Senate will see the field the same and be supportive of any such request going forward.

There is much at stake in Dubai. In this twenty-first century, a good reputation has evolved from being an optional extra for a rich country to a necessity. By this token the U.S. has to invest not only in the defense of its borders and its physical personnel and interests overseas, but to protect its image, its presence in people’s imaginations and the relevance of its values: this is its reputational security. The advancement of such a task by the U.S. is well-served by Expo 2020’s theme of Connecting Minds, Creating the Future. America’s strengths include its global leadership in innovation and the educational sector, but its rivals will be doing all they can to showcase their own prowess in the field, to stake their own claim and tell their own story as resonantly and memorably as possible.

But there is a greater prize. Expos are festivals of the future in the same way that the Olympics are festivals of sporting achievement (more folks attend the Expo than the Olympics), and the future is more than a simple spectacle, like a horizon lit by a setting sun. Visions of the future have the ability to reassure, to inspire, to rally and, maybe most importantly for our world right now, to wean humanity away from its most corrosive obsession: the past. Visions of the future are more than one way to move beyond global crises; they are the only way to do so. The world’s emergence from the Great War, the Second World War and the Cold War all required the articulation of a vision of the future attractive enough to inspire not only allies but adversaries as well. Expo 2020 has the potential to be a launch-pad for visions for the coming decades. As the Secretary of State concluded on July 29: “the world is counting on us.” The U.S. needs to be there.

Photo by Shawn Nystrand via Flickr | CC BY-SA 2.0

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 28

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.