For its relatively short history and small land area, Singapore’s range of nation branding efforts is ambitious, concerted and seemingly ceaseless. Its desire to establish and seal its reputation as a leading global...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

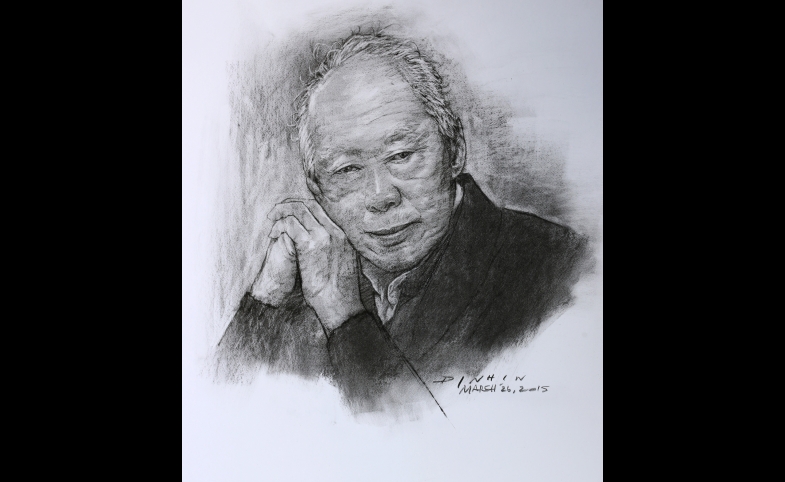

Lee Kuan Yew and the Middle East

Much of the Western news coverage of the death of Lee Kuan Yew has been characterized by grudging admiration for the rise of Singapore and tut-tutting about Lee’s autocratic style. The subtext is that anyone who fails to embrace Jeffersonian democracy as the ideal political system is unworthy of praise.

That same outlook pervades American foreign policy and is particularly obstructive in U.S. relations with the Arab world. American policymakers and those in many other Western countries tend to underestimate the appeal of fundamental domestic stability in countries that have rarely known it. Democracy remains an abstraction, but stability means food on the table and a roof overhead.

One of the best appraisals of Lee’s method of governing has come from Asia scholar Orville Schell. Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Schell notes that Lee, “instead of trying to impose Western political models on Asian realities, sought to make autocracy respectable by leavening it with meritocracy, the rule of law and a strict intolerance for corruption.” Lee based governance on “Asian values” rather than relying on outsiders’ norms, and anyone who has visited modern Singapore knows that the resulting achievements have been remarkable.

America’s interests in [the Middle East] would be best served not by constant political conflict, even under the guise of “democratic reform,” but rather something more along Lee’s approach, in Schell’s words, of “authoritarian leadership, constrained by certain Western legal and administrative checks.”

Lee’s concept of a political system built on indigenous values has resonance for the Middle East. In 2006, Lee observed that among Muslims, particularly in the Middle East, “there is a profound belief that their time has come and that the West has put them down for too long.” He added that militant Islam, a major destabilizing force in the region, “feeds upon the insecurities and alienation that globalization generates among the less successful.”

This reasoning is in line with realistic appraisals of the causes of the 2011 “Arab spring.” Popular support for the uprisings derived not from esoteric political idealism but from anger about the lack of personal dignity, deprivation that was rooted in the harsh realities of daily economic survival. When the tumult in the region finally settles down, it is likely that public support will rally behind leaders such as Egypt’s president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who leaves no doubt about his commitment to firm control of his country. It is far too early to judge Sisi’s competence and his plans for Egypt’s future, but he seems to be following Lee’s path in terms of being wary about the purported value of liberal democracy when it obstructs stability.

Of all the Western nations, the United States has been the most persistent – and perhaps the most naïve – about the suitability of American-style democracy in the Middle East. America’s interests in the region would be best served not by constant political conflict, even under the guise of “democratic reform,” but rather something more along Lee’s approach, in Schell’s words, of “authoritarian leadership, constrained by certain Western legal and administrative checks.”

Some may consider this kind of realism to be an ideological retreat and a surrender to prospective dictators. But the world as one wishes it would be and the world as it truly is are two very different things. Lee Kuan Yew understood that, and he found ways to bridge those different worlds.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

January 2

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.