In July 2015, Dr. Nancy Snow was named Professor Emeritus of Communications at Cal State Fullerton after an early retirement as Full Professor. This was her highest honor to date, but then in September 2015, she...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

China’s Charm Offensive: Beyond Appearances

Since the beginning of the 21st century, China has been a rising star in the arena of public diplomacy. Its PD campaign, coordinated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, involves fourteen separate Departments, including the United Front Work Department, the Ministry of Commerce, the Ministry of Culture, and the General Administration of Press and Publication. [1] The colossal campaign aims to brand China as a responsible, peace-loving, and culturally sophisticated nation. [2] China has done this through generous aid to Africa, the global expansion of its media properties, and the rapid growth of Confucius Institutes.

In the United States, almost every aspect of China’s public diplomacy campaign is labeled “assertive,” “aggressive,” or a “charm offensive.” Being Chinese, whenever I encounter such reports, I feel a sense of pride. China is probably experiencing its best years since the British Army burst open the gate of the Qing Dynasty with armor and cannons in 1840.[3] But this pride won’t last long. My reason soon retakes control, reminding me that under the centralizing structure of the Chinese government, formidable PD projects are nothing new. In the midst of the Cultural Revolution, during the 1970’s, the Government sponsored the Tanzam Railway, a 500 million dollar construction project that connected Tanzania and Zambia and mobilized thousands of Chinese workers.

The pertinent question is whether China’s current PD campaign achieves its goal. Is it successful? This touches on the issue of evaluation, a “hard nut to crack” in the sphere of public diplomacy.

When it comes to assessing PD, there are two main approaches. [4] One is to measure the output of PD effort, for example how many foreign students have enrolled in Confucius Institutes. The other goes beyond the activity itself and seeks to evaluate its outcome, often at a cognitive level. In the case of Confucius Institutes, a positive outcome would be participants’ increased understanding and favorability towards China, or more fundamentally, whether the presence of Confucius Institutes improves China’s reputation in surrounding communities.

The output approach is easier to quantify and track, and is often adopted by practitioners to justify funding. However, a high output does not necessarily bring forth positive PD outcomes; the soaring number of foreign students who study at Confucius Institutes does not lead to an indisputable victory in the battlefield of PD. The outcome approach, which “gets to the heart of assessing the effectiveness of public diplomacy,” is more reliable in this regard. [5]

In terms of its output, China’s PD program appears to be a booming success. It has been flexing its soft power through a wide range of PD channels, characterized by the troika of Confucius Institutes, foreign aid, and international broadcasting. Confucius Institutes and Classrooms, in a mere nine years, have swept across 117 countries, with 440 Institutes and 646 Classrooms. Beijing pledged $189 billion in foreign aid and government-sponsored investment activities in 2011, [6] investing $75 billion in aid projects in Africa alone from 2000 to 2011.[7] Chinese media property CCTV boasts three major global offices in Beijing, Washington, and Nairobi, and more than 70 additional international bureaus. Its program claims a reach of millions in 137 countries. [8] In an era when the budgets of the VOA and the BBC have been battered by funding cutbacks, CCTV’s output is staggering.

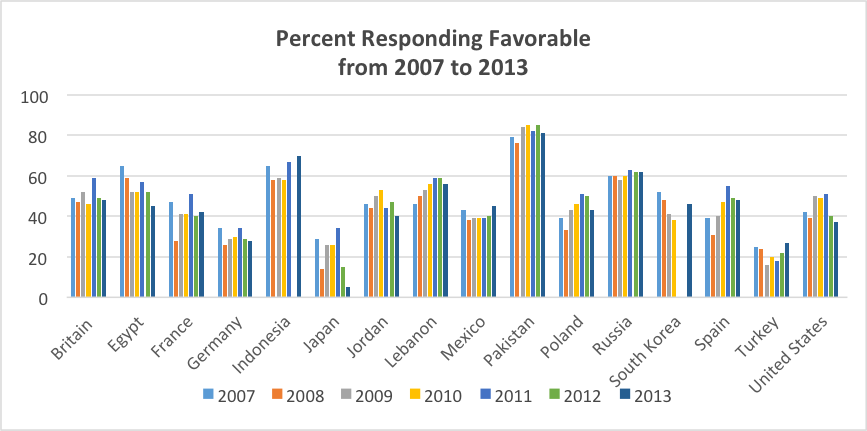

However, when it comes to the outcome of China’s PD, the result may be more disturbing than reassuring. Unlike its Western counterparts, China’s PD architects—who perceive China as misjudged and deserving of more respect—have paid greater attention to improving the nation’s image. In an online exchange in 2013, Qin Gang, China’s Director General of the Information Department, described public diplomacy as “an important means to introduce China and improve national image.” China’s Public Diplomacy Forums in 2011 and 2013 also revolved around the concept of image. [9] Nevertheless, based on data from the Pew Global Attitudes Project, China’s favorability in 16 sample countries was in flux from 2007 to 2013. Compared to the country's booming economic power, China’s image is in need of rebuilding.

In 2008, favorability towards China plummeted to the lowest point in the sample period, from a median favorability rate of 46.5 percent in 2007 to 41.5 percent. After 2008, there was an increase in favorability in the majority of sampled countries, with the median reaching its peak of 51 percent in 2011. In the past two years, the favorability rate showed a clear pattern of recession. Among the 16 sample countries, only Mexico, Indonesia, and Turkey exhibit favorability with an average 6 percent increase. In another survey conducted by the BBC, of the 25 countries surveyed in 2013, 12 hold positive views of China and 13 hold negative views. In Africa and the BRIC nations, China’s “performance” is seen in a more positive light. However, in the EU, the U.S., and Canada, as well as in neighboring countries like Japan and Korea, China is viewed in an “extremely negative” light. [10]

Figure 1: Percentage responding favorable in 16 countries from 2007 to 2013

Source: The Pew Global Attitudes Project database

Table 1: Percentage responding favorable in 16 countries from 2007 to 2013

Source: The Pew Global Attitudes Project database

The flux in favorability contrasts with the powerful appearance of China’s PD campaign. The high outputs in cultural diplomacy, foreign aid, and international broadcasting have not been translated into any tangible outcome in terms of a more positive image, which China has arguably put the most weight on. However, it would be unfair to jump to the conclusion that China’s recent PD efforts have failed. The long-term nature of PD requires a more tolerant view in the short term. The expansion of media properties and the establishment of Confucius Institutes may pay off years after the investment.

Indeed, China is not alone in waging a battle to improve its national image. At the recent Public Diplomacy Forum held in DC, a U.S. PD practitioner commented on the job security within the field of PD by stating if the goal of public diplomacy is to make the world like us (the United States), then we will never lose the job. This may sound like a joke, but there is more than a grain of truth in it. Both China and the United States have been investing in public diplomacy with a considerable output, however, the outcome, like increased favorability across the world, is limited.

I would like to conclude with words from Chairman Mao. In a meeting with two Latin American leaders in 1956, Mao said, “U.S. imperialism is very weak politically because it is divorced from the masses of the people and is disliked by everybody and by the American people too. In appearance it is very powerful but in reality it is nothing to be afraid of, it is a paper tiger. Outwardly a tiger, it is made of paper, unable to withstand the wind and the rain.” [11]

This view is certainly prejudiced, but it can be interpreted as a cautious note to all Chinese PD practitioners, as well as to their U.S. counterparts. Are the United States and China divorced from foreign audiences? Is our PD campaign a “paper tiger” that has a formidable appearance but is weak inside? Focusing more on a substantial outcome, rather than the output, should be a general trend that frames future PD efforts.

[1] Zhao, Shiren. “How to View Current China’s Public Diplomacy”(2013).

[2] d'Hooghe, Ingrid. “The rise of China's public diplomacy. Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendaell” (2007).

[3] The incident, barely known here in the States, is widely regarded by Chinese as the opening of “a century of shame.”

[4] Matwiczak, Kenneth. "Public Diplomacy: Model for the Assessment of Performance" (2010).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Wolf, Charles, Xiao Wang, and Eric Warner. "China's Foreign Aid and Government-Sponsored Investment Activities."(2013)

[7] Strange, Austin, et al. "China’s Development Finance to Africa: A Media-Based Approach to Data Collection." Center for Global Development Working Paper 321 (2013).

[8] Nelson, Anne. "CCTV’s International Expansion: China’s Grand Strategy for Media?" (2013).

[9] The topic for the 2013 Forum was set as “Advocacy and Dialogue: China’s Stories and Image in the Public Diplomacy Era.” The focus of the Forum was heavily steered towards “how to use public diplomacy to improve China’s image.”

[10] BBC. "Views of China and India Slide in Global Poll, While UK's Ratings Climb" (2013).

[11] Mao, Tse-tung. “U.S. Imperialism is a Paper Tiger” (1956).

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

January 2

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.