Mexico’s international image is in shambles. Once lauded as a promised land by the international media and markets, Mexico has completely lost its mojo due to an improper administration, plagued by scandals. At the beginning...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

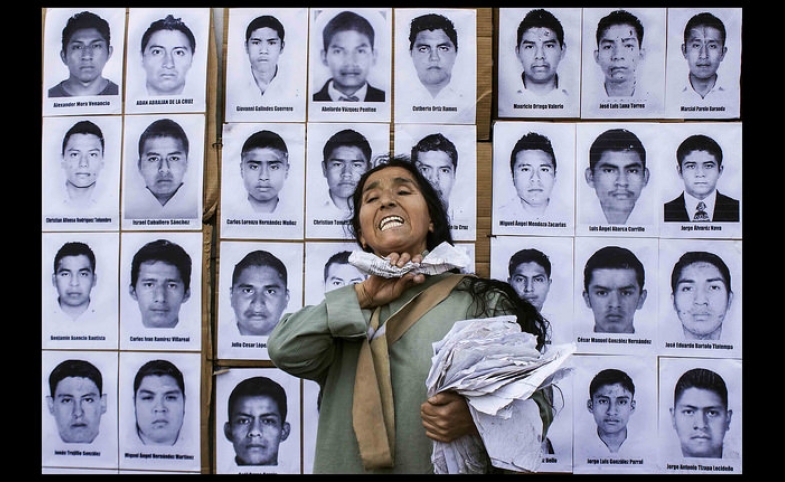

Crisis Over Missing Students Signals Mexico Tipping Point

Students in California are warming up for further protests against the UC regents plan for statewide tuition fee increases. Peaceful demonstrations are a rite of passage for college kids – an extracurricular activity teaching civil society and civic engagement lessons. But when hard battle lines are drawn and passions get high, the stakes get higher. Protests become exercises in civil disobedience, full of pushing matches or mass arrests.

They can also get extremely violent. Down the road in Mexico, student protests have a history of turning into blood sport. In 1968, student protests there turned into the Tlatelolco massacre. The official number of students killed ranges between 30 and 300, with still no reliable accounting. The 1968 events remain an open social wound in Mexico.

Recently, plans for aggressive student demonstrations in the state of Guerrero also turned lethal, resulting in the disappearance of 43 students, possibly mass murdered. The gory facts of the Sept. 26 abductions remain unclear, but the outrageous local attack against these students, along with delayed accountability, is now the greatest crisis the Mexican government faces.

In a country that has grown wearily familiar and indifferent with official graft, wanton drug-war-related killing and widespread lawlessness, the 43 students’ disappearance has sparked new levels of public outrage.

Local government authorities are suspected of conspiring with a drug gang to torture, kill, burn and dispose of the missing students’ bodies. The reason? The students were first detained by police and then allegedly handed over to the criminal Guerreros Unidos group in order to prevent a protest aimed at disrupting and spoiling a celebration for a local official’s wife.

It is a “let them eat cake” moment in Mexico. Aloof, callous and corrupt Mexican regional leaders stand accused of ordering cold-blooded murder, showing blatant disregard for human life. In a country that has grown wearily familiar and indifferent with official graft, wanton drug-war-related killing and widespread lawlessness, the 43 students’ disappearance has sparked new levels of public outrage.

What started out as a small protest against crime, corruption and the cozy relationships between drug gangs and powerful local government officials has now grown into a mass movement against the federal government, with increasing pressure on the 2-year-old presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto. The escalating demonstrations made it to Mexico City’s Zócalo, where protesters set fire to part of the presidential palace.

How Peña Nieto handles this specific crisis and, more broadly, addresses vice, inequality and injustice will determine if his government is prematurely and permanently hobbled.

Peña Nieto and his TV soap opera star wife have already been accused of personal financial impropriety. In response, Mexican first lady Angelica Rivera went on YouTube and defended the couple’s multimillion-dollar house purchase and later said she would give up the mansion. Reminiscent of Richard Nixon’s 1952 “Checkers” speech, her apologia (“I have nothing to hide,” she said) has probably mollified some. Peña Nieto promised further financial disclosures amid his own forceful campaign against corruption. But all this might not be enough to stop Mexico’s lingering resentments and current political slide into deeper crisis.

Students and their sympathizers may argue that it is all too little, too late. And Peña Nieto is already suggesting a targeted anti-government conspiracy movement is driving the current protest actions. But Mexican students may sense a historic tide sweeping them along. They may see the current crisis as an opportunity for dramatic social upheaval and forced change. There is certainly plenty of precedent for this around the world.

Aside from filling our own jails and morgues, drugs and guns have worked together to turn a young, vibrant and engaged Mexican student body into a rotting student corpse.

Students are often on the front lines of societal protest and change, some more civil than others. Just a few years ago in Egypt, they spearheaded the movement against Hosni Mubarak. In November 1973, striking Polytechnic students in Athens faced-off on campus against tanks and catalyzed broad public sympathy and a military junta’s end. Baby boomers recall the Paris street protests of May 1968, where 22 percent of the French working population joined Sorbonne students to paralyze President Charles de Gaulle’s government.

Earlier this year in Kiev’s Maidan Square, protesting students sent Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovich packing, and in Hong Kong today, students wielding umbrellas are calling for democratic reforms that have at least attracted Beijing’s attention though, thankfully, not their tanks. Burma, Iran, South Africa … there is a long list of countries where student protest is ongoing or has previously had significant societal impact.

Sometimes student protests are about immediate concerns – such as rising tuition – but oftentimes mobilization grows around grander issues of injustice, poverty, racial equality, religious freedom, environmental degradation, human rights, war and peace.

In Mexico, growing public discontent with long-decaying local government and law enforcement institutions appears to have reached a tipping point. Drugs and guns are widely corrupting contraband that have accelerated Mexican society’s devolution: drugs demanded primarily by our U.S. market, and guns that wend their way down south of the border. Aside from filling our own jails and morgues, drugs and guns have worked together to turn a young, vibrant and engaged Mexican student body into a rotting student corpse.

This post originally appeared in The Sacramento Bee.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 28

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.