The Gulf crisis has hit the eighth week of its diplomatic standoff. Prior to the trade siege, and right after the Qatar News Agency cyber-attack that U.S. intelligence officials now attribute to the UAE, the media voice...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

The Diplomacy of the Tunisian People and the Psychology of the Arab Street

“Hope” is the first lesson the Arab street is learning through the Tunisian experience. For decades, the Arab peoples have been depressed, felt helpless and had to live with the injustices, the failures and repressions of their post-colonial states. For the first time, an Arab people, Tunisians, have won against one of their regimes. The event had an echo among all Arab peoples. Many of them felt this strengthened their trust in themselves and their hope in the future. Hope and change did not have to come through the diplomacy of President Barack Obama or Nicolas Sarkozy in France, it came through the public movement in Tunisia, a country thought to be “very stable” for 23 years. Many of the Arabs are hoping for a domino effect from this revolution.

This past weekend Arabs were protesting in Tunisia and Algeria, in Cairo and Amman. Although poverty, unemployment and the deteriorating economic situations are the direct motivations for their move, political and social repressions, corruption and injustices are at the roots of this movement in Tunisia and wave of protests in the other countries. For decades, Arab populations thought they did not deserve better leadership after their disappointment with the late charismatic Gamal Abd Al-Nasser due to the defeat in the 1967 war with Israel -- a defeat that emasculated the Arabs and considerably shattered their self-image. In contrast, these past few days, an Arab population earned their freedom and achieved their purpose. Tunisians had been chanting in the streets for the past few weeks asking their president, Zain Al-Abideen Bin Ali, to leave -- and finally, he did.

Although the turmoil in Tunisia is far from over, for the time being, it is doubtful that similar revolutions will succeed and that the domino effect will reach other neighboring countries. Yet, it is important for the Arab peoples as much as for the regimes to recognize that regime change and popular public movements are possible scenarios. This new development dramatically changes the political equation in many of the Arab countries that had gained a reputation for stability over many decades, and in which the only perceived threat was Islamists.

Another important development of the story is the popularity if the legal discussion that followed the declaration of Muhammad Al-Ghannushi the Prime Minister of appointing himself the president of Tunisia. The basis for this appointment is article 56 of the Tunisian constitution. Many of the legal experts, politicians and observers were outraged by this appointment arguing that article 57 had to be used instead, and accordingly requesting another president. Arab media were discussing the legitimacy and the constitutional grounds of the moves in Tunisia. Legal frames and constitutional discussions are not that popular in the Arab media, and we owe thanks to the Tunisians for popularizing them.

Responding to this major change in the Arab scene, many Arab regimes felt obliged to declare short-term changes to demonstrate concern about the welfare of their populations; these included Jordan, Syria, Algeria and Yemen. These minor changes are intended to sooth the heated populations and stabilize their own regimes. Media in the Arab countries is anticipated to frame these changes to the Arab populations based on the respective political agenda of the various regimes.

Jasmine Revolution and Social Media

The internet effect on the Tunisian revolution was exaggerated by many. A few described it as the “Facebook Revolution” reminding us of the Iranian revolution against the re-elected president Ahmadinejad in June 2009 which was called “Twitter Revolution”. Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya presenters, for instance, referred to the significance and high quality of footage and videos contributed by individual Tunisians through social media, since both channels did not have reporters in Tunisia prior to the departure of Bin Ali.

The “Jasmine Revolution” in Tunisia was compared to the 1952 revolution of Nasser in Egypt. Many expected that this will have effects in other Arab countries. Al Jazeera focuses on the euphoria and the return of Islamists to Tunis especially Hezb An-Nahada (the Renaissance Party) leader Rashid al-Ghannushi, Al Arabiya focused on what they framed as a security loss in Tunisia. Al Jazeera kept emphasizing it as a message to Arab peoples and other regimes in the region, advising them to learn the lesson and change before they are forced to. The channel’s anchors dressed and spoke as though they were celebrating the revolution. Bakryah argues that the significance of the events in Tunisia is to convince Arab populations that democracy and freedom can be realized without U.S. or European support.

An important phase of the story has yet to be realized and narrated; that is, the final phase and conclusion of the revolution. This might have very important impact on both the peoples and governments in the region. Developments in the field send various messages. Nevertheless, obviously, the Tunisian revolution and the regime change are unprecedented in the modern history of Arab countries.

Many Arabs were using social media to send their congratulations and best wishes to each other, looking forward to the day in which other Arab countries are “liberated”. Many on Facebook changed their own profile pictures to the picture of the young Tunisian man who sparked the revolution, Muhammad Bu Azizi. Yemenis were reported to wish similar change for their own country on social media too. They published poetry, caricatures and images associating their own president Ali Abdallah Saleh with Bin Ali as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1: Bin Ali with the Yemini President Ali Abdalla Saleh as it appears on many Yemeni Face book pages.

During the past few days, the majority of the Arab press does focus on the lessons that should be learnt from the Tunisian revolution. Many writers, including Adnan Bakryah in Al-Mashad Al-Ekhbari threatened Arab leaders in Egypt, Algeria and other countries, and others posed the question of who is next. There is a great deal of euphoria shared among Arab writers for the first time in decades. Abd Al-Bari Atwan of Al-Quds Al-Arabi newspaper in London pointed out in an interview on Al Jazeera news channel on Saturday 15 January that this is the second Arab revolution after Nasser’s 1952 revolution in Egypt.

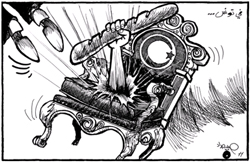

Khalid Hroub, director of the Cambridge Arab Media Project (CAMP) emphasized the significance of the semi-absence of Islamists from this revolution and that the development of a good government and the success of the Tunisian experience to build a stable democratic regime will undermine the popularity of Salafi Islamic political wave. The trend in the Saudi media was to present the “Jasmine Revolution' in Tunisia as a ‘for bread revolution’ which brings about serious security risks and consequences. Al-Hayat newspaper in London has a caricature for Habib Haddad emphasizing bread as the weapon that weakened the regime of Bin Ali (see Figure 2). This framing was popular in other Saudi news outlets.

Figure 2- Habib Haddad-Al-Hayat newspaper, London January 16, 2011

When comparing the coverage of Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya of the revolution one finds important disparities. Al-Jazeera seemed to be the cheerleader of the revolution enhancing the positive impact of the events in Tunis, whereas on the other hand, Al Arabiya, as many in the Saudi media were more focused on the looting, killing and exaggerated instability in the country due to the revolution. Saudi Arabia was highly criticized in Al Jazeera for accepting Bin Ali in the country.

Tunisian Lesson and the “West”

The United States and France were highly criticized by for the lack of any positive support of the Tunisian people against the repressive regime during the last few weeks that preceded the departure of Bin Ali. President Barack Obama did not make any comment till the day after the Tunisian president left the country on Saturday, January 16. France, in their first statement, described the events in Tunisia as a natural consequence of the global financial crisis, failing to acknowledge the political and social repressions of the Bin Ali’s regime.

An editorial in the Syrian newspaper Al-Watan argues that the “West” has a lesson to learn, as Bin Ali was one of their closest allies. The editorial fell short of recognizing any resemblance between the Syrian and Tunisian regime and to acknowledge the lesson their regime has to learn. Clearly there is a fierce contestation of framing and interpretations of this revolution, whether as a mechanism of self-defense or as a tool of motivation and hope.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.