Like many other technologies, digital platforms come with a dual-use challenge that is, they can be used for peace or war, for good or evil, for offense or defense. The same tools that allow ministries of foreign affairs...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Lessons from the Evolution of Digital Diplomacy

When writing about digital diplomacy, scholars tend to focus on its present practice and future potential. Yet we may also benefit from exploring its past and identifying the processes and events that have contributed to its evolution.

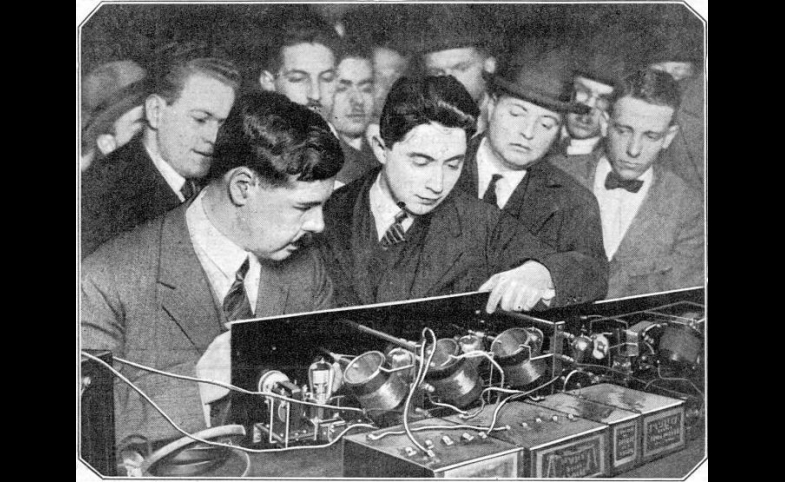

Diplomacy's evolution has always been linked to changes in the societies which it serves. For instance, diplomacy altered dramatically following the formation of the modern sovereign state which saw the birth of the resident Ambassador. Likewise, diplomacy has always been impacted by technological revolutions such as the radio, which contributed to the advent of public diplomacy. Bjola suggests that the main task of the resident Ambassador was to manage relations of enmity or friendship at foreign courts. Thus, diplomacy has had a social aspect to it for several decades. Dizard argues that diplomacy was first digitized when MFAs employed telegraph clerks in the 19th century. So the very characteristics of digital diplomacy, whether social or digital, are not necessarily new, but are part of diplomacy's ongoing evolution.

However, one cannot deny that there are new facets to digital diplomacy, namely the use of social media in order to foster dialogue between nations and foreign populations. When attempting to identify the events that contributed to the emergence of digital diplomacy, most scholars point to three events. The first is the Arab spring. As Philip Seib argues, most nations failed to anticipate these democratic outbursts as they were not listening to important conversations taking place between Egyptians or Tunisians online. Governments soon realized that if publics were now assembling online, they had to be online as well.

The second event was the birth of the citizen journalist, made possible by social media outlets such as Facebook. Armed with cell phones, protestors in Ukraine's Orange revolution or Iran's Green revolution were able to disseminate information regarding what was happening in their countries to a global audience. The speed with which information was now available online demanded that governments react just as quickly. Doing so meant that governments too had to monitor the information available on social networks.

The third event was terror groups' use of the internet in order to spread their ideologies and narratives following 9/11. Countering this narrative also prompted governments to go online.

...The very characteristics of digital diplomacy, whether social or digital, are not necessarily new, but are part of diplomacy's ongoing evolution.

But what is it that connects all these events? What is their common denominator? Perhaps it is the merging of the offline and online worlds that occurred at the beginning of the 21st century. In the early days of the internet, anonymity was everything. People partaking in chat room conversations had user names that masked their true identity. Yet during the early 2000s, with the advent of Facebook and the like, our online and offline worlds merged. Thus revolutions that start online erupt offline, and terror groups that strike offline recruit online. Likewise, since citizens began to exist online and offline, so did governments.

In fact, once this merging occurred governments were quick to explore the online world in e-gov initiatives. Foreign ministries are therefore by no means the first branch of government to join cyberspace. By viewing the migration of governments in general to the online world as a process that contributed to the evolution of digital diplomacy, scholars and practitioners may be able to benefit from lessons and insights gained by other branches of government. Such lessons may not only contribute to the practice of digital diplomacy, but may also shorten its learning process.

One example is e-health initiatives. Health ministries were among the first to adopt new Information Communication Technologies (e.g., internet, cell phone) in order to deliver health behavior interventions such as helping people to quit smoking. Early interventions showed little success. This altered with the notion of "tailored health interventions," which delivered information that met the unique characteristics of each participant. For instance, the text2quit smoking cessation program, developed by U.S. public health academics and now available to the general public, delivers personal messages to a participant's cell phone which take into account the reason he quit smoking and his smoking habits. Thus someone who smokes mostly in the evening would receive text messages after work hours saying, "John: you said you wanted to quit smoking so you could see your son graduate college." Tailoring has proven much more affective in health behavior change than targeting, which is authoring health-related messages to an entire social group such as teen smokers.

Tailoring could prove valuable to foreign ministries (MFAs) as well. Currently, digital diplomacy is based on targeting, as MFAs deliver information to a global population. Moreover, embassies often re-tweet MFA authored content. Yet such messages may be completely irrelevant to the embassy's followers, as the manner in which a nation is seen differs from country to country. For example, the U.S. has a different reputation in Israel and in Pakistan. Likewise, the relationship between the U.S. and each of these nations differs as do the social, cultural, and economic characteristics of each country. In order to increase the impact of digital diplomacy messages, embassies should tailor content to the unique characteristics of the local population.

Another example is Estonia, or "eStonia", which is one of the most connected nations in Europe, offering citizens the ability to conduct all interaction with their government online including e-elections, e-banking, e-police and e-school. Yet such E-gov services were also not developed overnight. They are a result of a decades-long learning process in which various ideas and systems were tried and evaluated, as is evident from early studies which stated that, as a whole, "E-gov remains in its infancy".

Currently, digital diplomacy, too, is in its infancy. MFAs and diplomats around the world are attempting to migrate to the online world, a demanding task. Yet if MFAs strive to learn from digital diplomacy's ongoing evolution, one impacted by technology, geopolitics and governments’ overall desire to meet its citizens online, they may discover the tools and experience necessary to successfully practice diplomacy in digital surroundings.

Suggested Reading:

Seib, P. (2012). Real-time diplomacy: politics and power in the social media era. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bjola, C. (2013). Understanding Enmity and Friendship in World Politics: The Case for a Diplomatic Approach. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 8(1), 1-20.

Roberts, W. R. (2007). What Is Public Diplomacy? Past Practices, Present Conduct, Possible Future. Mediterranean Quarterly, 18(4), 36-52.

Junio, T. (2012). Marching Across the Cyber Frontier: Explaining the Global Diffusion of Network-centric Warfare. Cyberspaces and Global Affairs, 51.

Dizard, W. P. (2001). Digital diplomacy: US foreign policy in the information age. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Abroms, L. C., Ahuja, M., Kodl, Y., Thaweethai, L., Sims, J., Winickoff, J. P., & Windsor, R. A. (2012). Text2Quit: results from a pilot test of a personalized, interactive mobile health smoking cessation program. Journal of health communication, 17(sup1), 44-53.

Dixon, B. E. (2010). Towards e-government 2.0: An assessment of where e-government 2.0 is and where it is headed.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.