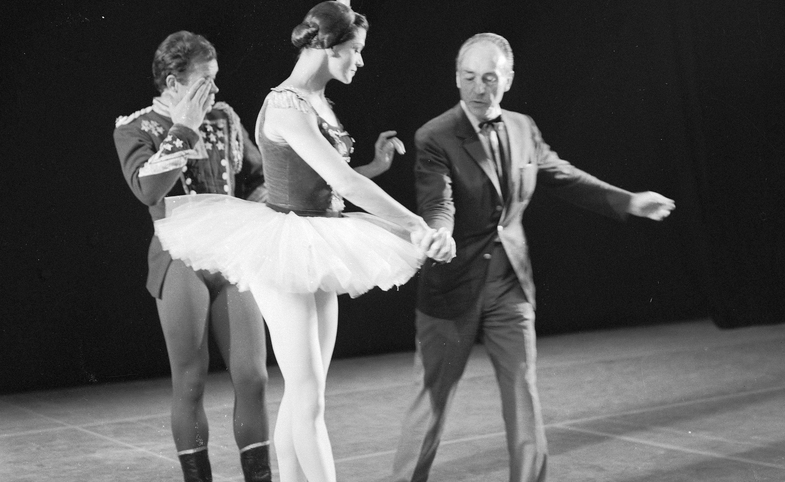

Ballet diplomacy takes center stage at the Lincoln Center in New York City in a performance of George Balanchine's Jewels. It features three periods of his life: "Emeralds" for his time in Paris in the 1920s, "...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

George Balanchine: The Public Diplomat Beyond the Ballet Master

Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union shaped the historical reality of the modern world. Given the current tensions between the United States and Russia, it is worth keeping in mind the past successes of U.S. cultural diplomacy. During the Cold War, one such success involved choreographer George Balanchine.

Almost everyone in the world has heard about the New York City Ballet. Many have attended its captivating shows. On one hand, nearly everyone in the U.S. and the country of Georgia is aware of George Balanchine, artistic director of the New York City Ballet and founding father of the American ballet industry whose artistic vision inspired generations of ballet lovers. On the other hand, only some people know him as George Balanchivadze. And probably none of them have thought about him as a public diplomat who aesthetically spread the word about the American ballet industry in the Soviet Union’s big cities, including Tbilisi. Balanchivadze is George Balanchine’s Georgian last name, and as a part of the New York City Ballet’s Soviet tour in the 1960s and 1970s, he was an artistic U.S. public diplomat in his ancestral country of Georgia.

In the midst of the Cold War, bilateral agreements between the U.S. and the USSR on exchanges in cultural, technical, and educational fields made it possible for the people living on both sides of the Iron Curtain to exchange ideas in the field of choreography. While the Bolshoi Theatre aimed to project the cultural advancement and superiority of the Soviet Union in the U.S., American choreographers tried to share messages about American values from stages in Soviet cities. Spreading values through cultural programs, including ballet diplomacy, was a powerful element of U.S. public diplomacy programs during the Cold War, and the New York City Ballet and George Balanchine were not exceptions. However, Balanchine’s visits in Tbilisi, Georgia, from both personal and public diplomacy perspectives, were exceptional for several reasons. First, although born into the family of noted Georgian Meliton Balanchivadze, one of the founders of Tbilisi Opera and Ballet Theatre, Balanchine had never visited his ancestral country before. When the New York City Ballet was staged in Tbilisi, it allowed Balanchine to reunite with his brother, family home, and relatives. Moreover, to Georgians, he represented a man who had achieved his dream through hard work in the land of freedom, where aspiring toward a brighter future was very welcome.

Every move of the New York City Ballet’s dancers represented freedom, independence, integration, joy, happiness, hope, and a step toward a brighter future for Soviet Georgians.

These visits creatively bridged the country of Georgia, a place of Balanchine’s origin, and New York, the birthplace of his career. His visits with the New York City Ballet in Tbilisi in 1962 and 1972 represented the triumph of creative meetings between U.S. and Georgian societies. This was the power of creativity that would someday melt the Iron Curtain to openly connect these people so they could talk endlessly about ballet, music, and dancing.

How did these visits influence Balanchine's career as a choreographer? Generally, public diplomacy programs fully benefit all sides involved. Hence, the New York City Ballet’s visits in Georgia were beneficial to Balanchine as an American choreographer. For a long time, he had been thinking of creating stage dances with Georgian music, and his aspiration to use polyphony in ballet shows was one of the reasons for his strong desire to achieve this goal.1 These visits were a step forward to reaching this goal. Georgian folk dances made an unforgettable impression on him. While watching these, he stared at dancers in order not to miss their moves and gestures. Moreover, the warm welcome and huge applause made Balanchine happy and inspired him to make new, interesting works in the American ballet industry based on his Georgian experience.2

Balanchine was a skilled public diplomat. He respected the warmth and hospitality expressed by Soviet people toward him and the New York City Ballet and was sure that cooperation based on the creative contacts between Soviet and American artists was beneficial.3 As a choreographer and artistic public diplomat, Balanchine never stopped creating new ways to connect societies through ballet. Since many New York City Ballet shows were staged with Soviet composers’ music, he even looked forward to feedback from the Soviet choreographers.4

George Balanchine’s visits as an artistic public diplomat in his ancestral country of Georgia were an interesting public diplomacy experience. The United States is a nation of immigrants; American people, with origins from around the world, use their expertise and knowledge to benefit U.S. culture and society as a whole. Involving them in public diplomacy programs that represent America worldwide in their ancestral countries can give hope to the people with whom they connect. The Americans’ stories can be inspirational and motivational to them.

George Balanchine, who had immigrated to the U.S., used his creative freedom in public diplomacy to aesthetically advance the field of choreography. Moreover, he turned out to be an outstanding public diplomat. Balanchine’s visits to Georgia, which to him marked his rebirth,5 narrated his American success story to Soviet Georgians. Every move of the New York City Ballet’s dancers represented freedom, independence, integration, joy, happiness, hope, and a step toward a brighter future for Soviet Georgians. Importantly, these values were part of Balanchine’s life, and Georgians strongly believed in them. They believed in these values even more strongly because they were narrated by the New York City Ballet staged by George Balanchine of Georgian origin, the man of whom both Georgians and Americans could be proud. This shared pride was the foundation on which Balanchine’s success as a public diplomat was built.

1 George Balanchine: Music is Dancing, Dancing is Music. Soviet era Georgian newspaper “Communist”. October 8, 1972.

2 Call of a Parent. Soviet era Georgian newspaper “Flag of Lenin”. December 16, 1963.

3 G. Balanchine: Joy of Creative Meetings. Soviet era Georgian newspaper “Communist”. October 11, 1972.

4 Ibid.

5 Balanchine and Balanchivadze. Soviet era Georgian newspaper “Homeland”. May, 1983.

Photo by Ron Kroon | CC BY-SA 3.0 NL

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

January 2

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.