Note from the CPD Blog Manager: The views expressed in this article are the author's own and not necessarily those of the U.S. government. The United States’ reengagement with the world presents an opportunity for...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

PD to Advance Black Racial Solidarity: African American State Actors & Symbolic U.S. Diplomacy

Note from the CPD Blog Manager: This is part of a series by CPD Research Fellow Shearon Roberts on the use of public diplomacy in advancing racial justice and Black racial solidarity. This installment shares the diplomatic framework of Black U.S. political actors as the architects of global racial justice.

In 2020, four different public polls indicated that the Black Lives Matter movement’s protests may likely have been the largest movement in U.S. history. Roughly between 15 million to 26 million Americans indicated that they participated in protests to advance racial justice and equity. Data scientist Alex Smith mapped a total of 4,446 sites around the world where protests took place in solidarity with African Americans. From Hong Kong to Syria, across Europe to Brazil, global citizens called for racial justice, toppled symbols of historic oppression, and spoke out against white supremacy. On February 1, at the start of Black History Month in the U.S., the Black Lives Matter movement was nominated for the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize.

For state actors, racial justice is also being integrated into political and diplomatic language. At President Joseph R. Biden’s inauguration on January 20, 2021, the 46th U.S. president was recorded as being the first American president to use the words “white supremacy” in an inauguration speech. The Biden administration has since followed up these symbolic words with policy actions. In his first 30 days of office, Biden has signed a total of four racial equity and justice executive orders. Biden’s racial justice policies are being spearheaded by cabinet member Susan Rice, his domestic policy adviser. Rice’s last political appointment was as Ambassador to the United Nations (UN) during the Obama administration.

The role of Black U.S. political actors as the architects of global racial justice, as state actors who advance racial justice as a diplomatic framework, is not new in American history. The pursuit of racial justice by African Americans has been as much an inward project in American history, as much as it has been an external one of fighting against global forms of racial oppression.

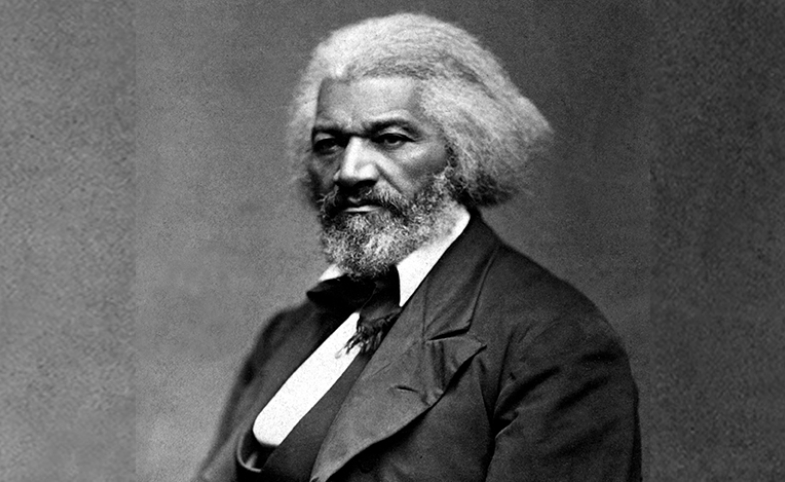

Frederick Douglass

On June 26, 1889, abolitionist Frederick Douglass was appointed by President Benjamin Harrison to serve as U.S. Minister Resident and Consul General for Haiti, the world’s first Black Republic. Haiti championed Black racial justice and solidarity in its first 100 years as a nation, spearheading decolonization in Latin America and engagement across the Black Atlantic. There was much to learn from Haiti, and Douglass recognized that.

At this point in his public life, diplomatic historian Louis Martin Sears wrote that Douglass was viewed globally, particularly after the Civil War, as the “undoubted leader of the colored race in the United States.” Douglass’ selection by the White House was symbolic. It was an early form of public diplomacy aimed a racial solidarity. Sears wrote, “The appointment of Douglass to the Haitian mission was official recognition of his race in the United States and at the same time a conciliatory gesture to that race in Haiti. From the Administration’s viewpoint, it was intelligent and a liberal move.”

Douglass’ mission to Haiti and his diplomatic work there conflicted him, and his writings often reflected the imperialistic goals of the U.S. at the time. Yet, Douglass still spoke admirably in 1893 in Chicago about the Haitians and their ability to self-govern:

"I shall in any degree promote a better understanding of what Haiti is, and create a higher appreciation of her merits and services to the world; and especially, if I can promote a more friendly feeling for her in this country and at the same time give to Haiti herself a friendly hint as to what is hopefully and justly expected of her by her friends, and by the civilized world, my object and purpose will have been accomplished."

Andrew Young Jr.

New Orleans native Andrew Young Jr. rose through the ranks of the Civil Rights movement as one of the closest friends to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He served as the executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and later became the first African American appointed to serve as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations by President Jimmy Carter in 1977.

Prior to Young’s rise to global diplomacy as a Congressman and head of the Congressional Black Caucus, he engaged in numerous foreign policy debates to leverage U.S. political might to decolonize Portuguese Africa in the early 1970s.

In Andrew J. DeRoche’s Andrew Young: Civil Rights Ambassador, DeRoche wrote that as the nation’s first Black UN Ambassador, Young was the designer of the Carter administration’s policy toward Africa. Here in the U.S., the Carter administration recognized Young’s role in galvanizing the African American vote in securing a Carter victory in 1976. The Carter administration, in return, centralized human rights efforts globally, particularly for people of African descent, as part of its foreign policy. DeRoche wrote, “Young’s civil rights background and informal style of diplomacy contributed to many foreign policy successes in the first year of Carter’s presidency.”

Douglass, Young, Rice and Thomas-Greenfield’s diplomatic careers are rooted in their own connection to lived racial injustice in the U.S.

Susan Rice

Like Young, Rice also became the first Black U.S. woman ambassador to the UN in 2009, and the Obama administration restored the position to its original cabinet-level stature. Rice’s father was a Tuskegee Airman and the second Black governor of the Federal Reserve system. Her public service was deeply shaped by her parents’ global work in understanding the developing world.

Rice first rose through the diplomatic ranks after serving as Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs during the Clinton administration. Despite criticism of her time as ambassador, the diplomatic community has since reaffirmed her record of shaping human rights policies in Africa. In an open letter supporting her role in the current Biden administration, Rice was noted for her efforts to “make America a true partner in Africa’s development” and in “changing how Americans view the continent.”

Linda Thomas-Greenfield

Like Rice, the Biden administration’s recently appointed Ambassador to the UN Linda Thomas-Greenfield, a Louisiana native who grew up during segregation, first served in shaping U.S. policy through the bureau of African Affairs. Thomas-Greenfield has noted in her confirmation hearing on the importance of the U.S.’s re-engagement with the African continent in ways that provide alternatives to China’s growing diplomatic and economic engagement there.

Thomas-Greenfield coined the term “gumbo diplomacy,” her people-to-people approach of coming together around the table to solve differences. In her official tweet after her nomination, Thomas-Greenfield asserted that “global change relies on diplomacy and building relationships with people around the world. We need our allies. We need our partners. We need our friends.”

Douglass, Young, Rice and Thomas-Greenfield’s diplomatic careers are rooted in their own connection to lived racial injustice in the U.S.

As state actors not always in the driver’s seat of U.S. policy, they sought to execute the foreign policy of the most powerful nation in the world when the work of equity and justice at home remained delayed and deferred. Their symbolic presence as Black state-actors who represent a powerful nation, of which such rare roles provided them the space to make small gains in global racial justice, is arguably their most enduring soft power act of diplomacy.

As Black diplomatic actors, their efforts to amplify the humanity of people of African descent across the globe, while elevating those at home, remains at the core of what a framework of Black public diplomacy can achieve.

Photo: Frederick Douglass circa 1879. National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives Identifier (NAID) 558770. Public domain.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

March 9

-

January 28

-

February 6

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.