COVID-19 has brought attention around the world to many Indian traditions that promote and sustain good practices for mental, physical and spiritual health. Foremost among them is the Namaste, a greeting that has been...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

In Senegal, American Soft Power Shows Resilience

In the past three years, the world has seen a rapid decline in American soft power. The United States has fallen to fifth place on the Soft Power 30 and, globally, only 27 percent of the world’s population have confidence in President Trump’s ability to navigate world affairs. For public diplomacy practitioners, this is sobering news, as the ability to effectively communicate with a foreign country’s population is diminished by shaky foreign policy decisions and slashed diplomatic budgets.

Yet exceptions to this troubling trend can still be found in Sub-Saharan African countries, where confidence in American leadership persists and where Trump’s approval rating can exceed 60 percent. As a student currently living in Dakar, Senegal, I have noticed firsthand that America’s ability to attract and influence remains strong.

The relatively small country of Senegal is one of West Africa’s most stable democracies and an important U.S. ally in a region where violent extremism and instability continues to grow. To strengthen this relationship, the U.S. has signed multiple military agreements including a defense cooperation deal in 2016. In addition, they have also managed to foster a positive image with the nation’s population. Although America’s approval rating in Senegal suffered a loss at the beginning of Trump’s administration, U.S. leadership approval has remained unchanged from 2017-2018 and hovers at 48 percent (on the higher end globally).

Despite the lack of public diplomacy initiatives from the Trump administration in this region of the world, American culture and identity has still been able to foster positive bilateral relations with many in the Senegalese public.

This sense of goodwill is palpable. Upon arriving in Dakar, I was quickly surprised by the level of positivity I received when revealing my American identity. Due to America’s historical role in the Transatlantic Slave Trade accompanied by President Trump’s inflammatory generalization of Sub-Saharan African nations as “s***hole countries,” I had prepared myself for hostility. Instead, I have found the mention of America to be generally met with positivity and admiration. From a local Dakar street vendor who announced his love of America whilst wearing a U.S. Navy shirt, to my interaction with Fatou Mané, the elderly queen of the island Sipo, who expressed excitement that my group was American and not French. These events have indicated that despite the lack of public diplomacy initiatives from the Trump administration in this region, American culture and identity is still able to foster positive bilateral relations with many in the Senegalese public.

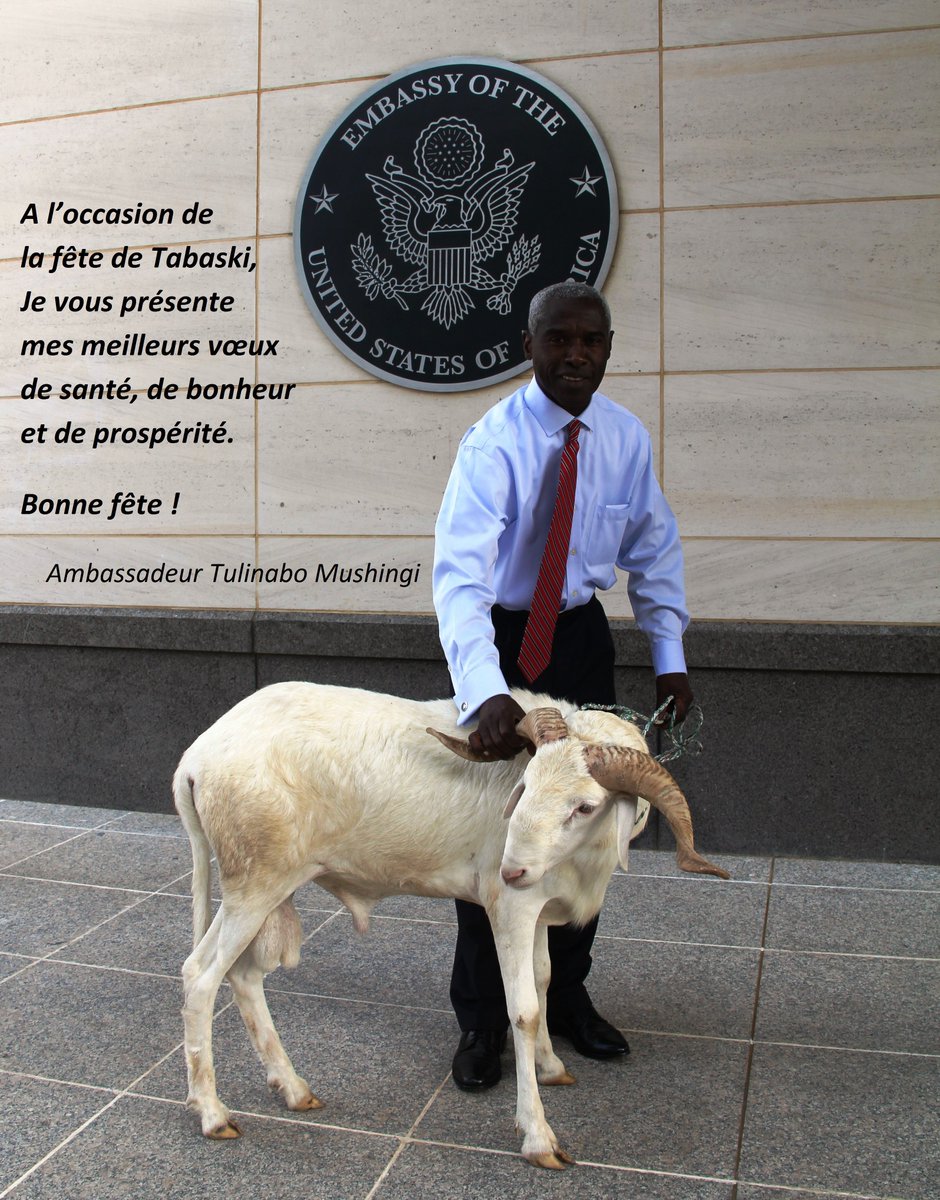

In fact, Trump’s laissez-faire approach to Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the most evident reasons America’s reputation has continued relatively unscathed. Embassies in this region have free reign to promote public diplomacy initiatives without the shadow of a Trump presidency looming overhead. For example, U.S. ambassador Tulinabo Salama Mushingi enjoys a popular reputation and is considered to be very open to Senegalese culture. Ambassador Mushingi has proven adept at conducting his own public diplomacy through social media. His tweet posing with a sheep for Tabaski (the most important holiday in Senegal) was applauded by news outlets such as BuzzSenegal, DakarBuzz and Seneweb.com as a welcome effort of a western nation integrating with Senegal’s Islamic tradition.

Photo courtesy of the author via Twitter. U.S. Ambassador Tulinabo Salama Mushingi's photo honoring Tabaski. Translation: "On the occasion of the Feast of Tabaski, I present to you my best wishes of health, happiness and prosperity. Happy feast!"

Even more surprising is that President Trump’s rhetoric has actually resonated to some in the population. Although many Senegalese people will poke fun at America’s current administration, others have expressed a type of admiration. One Senegalese professional studying at an English language school close to my home voiced his support of President Trump for being the type of leader who will put his people first. Considering Senegalese independence was not won until 1960, its official language does not reflect an African identity and its trade agreements heavily favor the French economy, a Senegalese version of “America First” could find strong support. American soft power is determined by how its conduct affects international populations, and Trump’s brand of nationalism is received well by a segment of the population.

Finally, America does not have to rely solely on public diplomacy initiatives to promote its image when France is acting as its foil. My time in Senegal has revealed to me a distinct anti-France sentiment, especially with the younger population. In fact, the activist group FRAPP graffitied the French equivalent to “Get Out France” throughout Dakar in protest against the tight grip French companies have on the Senegalese economy. This group argues that French transnational retailers, such as Auchan and Carrefour, have pushed Senegal’s large population of small traders under financial duress throughout the country. During a personal interview with one of my acquaintances, university student Yatta Dia, this sentiment was reflected. Yatta explained that France’s interference in Senegal (during and post colonization) and tendency to impose its laws and worldviews on the country have led her, along with many others, to view the country negatively.

However, the U.S. does not have such close economic ties to Senegal, and the population living within the country consists mainly of those working in U.S. government or students. Therefore, it is unsurprising that Yatta’s opinion of the U.S. was favorable, telling me that the limited U.S. involvement with Senegal is good for the country and its reputation has remained unchanged throughout different administrations. As most in the Senegalese population see France’s involvement as detrimental, the small U.S. presence in Senegal is able to interact with the Senegalese population and strengthen bilateral relations free of the same frustrations reserved for France.

In my experience, the strength of American soft power in Senegal, is based more on the region’s tendency to be overlooked by the federal government and the complexity of post-colonial relationships than the success of wider U.S. public diplomacy initiatives. Therefore, in certain contexts, is the best public diplomacy no public diplomacy? Perhaps providing space for diplomats to chart their own PD paths could reap similar benefits around the world.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 28

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.