The United States, which introduced the concept of soft power to the world and increased the positive awareness of its country in the world through this concept, is one of the countries that uses cinema diplomacy most...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Boycotts and Public Diplomacy: Lessons from Algeria

Calls for consumer boycotts and ethical consumption are commonplace in developed democracies. Yet, while early scholarship on boycotting saw it as a phenomenon only in developed democracies, we find that it is also practiced in non-democratic countries, including in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Brands like Coke and McDonalds are powerful symbols of U.S. culture that are desired by many foreign citizens and shunned by others. From the Arab League boycott of Israel, which began after Israeli independence in 1948, to the recent Boycott, Divestment, and Sanction (BDS) movement against Israel and the Saudi-lead boycott of Amazon’s Souk, observers may wonder how likely consumers are to take their intentions to the cash register.

Yet we show in an article published in Politics, Groups and Identities based on our research in Algeria that boycotts of U.S. goods, while common, are unlikely to be effective unless they target substitutable goods that are visible and symbolic of identity, such as beverages and clothing. Boycotts are likely to be more successful for these product types because they reduce direct and information costs and enable social network enforcement.

The susceptibility of symbolic U.S. products to boycotting intentions, expressed by 60 percent of Algerians, illustrates the powerful link that citizens draw between products, brands and the nations that design and produce them. For public diplomacy practitioners, this highlights the strong potential of business and trade relationships to directly speak to foreign publics.

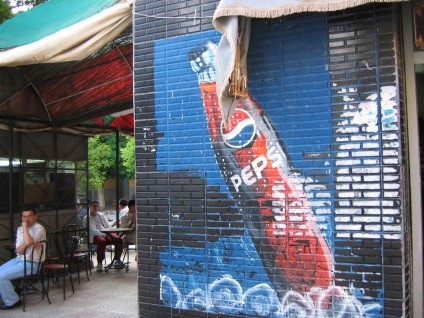

McDonald’s does not have franchises in Algeria, but restaurants such as McAmin’s, McQuinze, and McCool appropriate the logo as branding strategies. Shops advertise Coca-Cola and Pepsi, while others serve Mecca Cola, Selecto or other local drinks. © Megan Reif 2004.

How We Conducted our Research

We surveyed 820 Algerian students after the 2004 Abu Ghraib scandal and 780 Algerians in 2007 in a nationally-representative sample in order to evaluate the extent of boycott participation and the conditions under which citizens are more likely to translate their intentions into buying choices. We asked about soda, clothing and mobile phones. Coke and Pepsi are locally-produced and compete with Algerian and Arab beverages such as Ifri and Mecca Cola. A few American clothing brands are available, and knock-offs are common. Algerians can choose between the American mobile phone brand, Motorola, and Asian and European brands.

We found that almost 60 percent of Algerian students claimed to be boycotting U.S. goods, whether phones, clothing or sodas, and this was consistent with a nationally representative survey conducted in 2007 by Lindsay Benstead and Ellen Lust. We asked whether international events such as the Iraq war influenced the respondents’ consumption of American products during the past two years. In the student survey, 30 percent said they had never thought about changing American product consumption (“indifferent consumers”), 14 percent either did not change or reported consuming more U.S. products (“resilient consumers”), and 57 percent consumed fewer (“political consumers”). The findings were similar in the nationally-representative survey (Table 2).

Table 2 Consumer types

|

|

Political “Yes” |

Resilient “No” |

Indifferent consumers “Not thought about it” |

Total |

|

Student sample (2004) |

413 (57%) |

100 (14%) |

215 (30%) |

728 (100%) |

|

National sample (2007) |

408 (60%) |

94 (14%) |

178 (26%) |

680 (100%) |

But we found that despite Algerians’ widespread desire to boycott U.S. goods, few follow through unless the product is a substitutable good that is closely linked to identity (symbolic and visible) which reduces direct and information costs and enables social network enforcement. Consistency between self-reported boycotting and brand preference is higher for soda—a visibly-branded product that is substitutable, consumed publicly, symbolic of identity, and associated clearly with country-of-origin—than for clothing, which has similar features but low brand visibility. For mobile phones, which had few substitutes in 2004, and have low symbolism, brand visibility and country-of-origin clarity, boycotters are no more likely than others to avoid an American brand.

Boycotting is Common in the MENA Region

U.S. products are increasingly available in Algeria, which is America’s third-largest MENA trading partner. Yet as a result of the long-standing Israeli-Palestinian conflict and U.S. support for the Israeli position as well as the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, calls for U.S. boycotts have increased not only in Algeria but also across the Muslim world through state-regulated mosques, media outlets and social organizations.

Man in photo wears jeans and Nikes, while woman wears traditional (left) © Lindsay Benstead 2004. Western clothing (right). © Megan Reif 2004.

Boycott participation varies in the Arab world, according to survey research that we and others have conducted. According to the Transitional Governance Project, participation is low in some countries (14 percent in Tunisia, 18 percent in Libya) and high in others (31 percent in Jordan), suggesting that geographical proximity to Palestine and Iraq is a key explanatory factor. Boycotting is likely to be higher in countries directly affected by U.S. actions, such as drone strikes, or in countries like Jordan or Saudi Arabia where external support is critical to regime survival. Levels of anti-Americanism may also explain these differences. The Arab Barometer (2006-2008) found that proportions of respondents with negative views of Americans as people were high in Jordan (68 percent), Palestine (61 percent), and Algeria (48 percent), but low in Lebanon (16 percent). Negative views of American culture in general varied similarly—49 percent (Jordan), 40 percent (Palestine), 37 percent (Yemen), 32 percent (Morocco), 31 percent (Algeria), and 14 percent (Lebanon).

Public Diplomacy and Business

To be sure, this research was conducted in Algeria and may not apply everywhere, but it is already powerful evidence that Middle Eastern citizens despite—or perhaps because of their authoritarian governments—engage in ethical consumption. Yet boycott campaigns may not harm their targets. Our study suggests that boycotts rarely work because few target substitutable goods closely linked to identity (symbolic and visible) which reduce direct and information costs and enable social network enforcement.

That boycotts are so appealing highlights the powerful link between nations and products their companies and entrepreneurs design, produce and market. Public diplomacy practitioners can partner with the private sector to build bridges with foreign publics by producing goods they desire and, ideally, developing business relationships with local firms to produce and sell goods.

This piece was authored by Lindsay J. Benstead and Megan Reif. Benstead is a CPD Research Fellow (2017-19) and Associate Professor of Political Science in the Mark O. Hatfield School of Government and Interim Director of the Middle East Studies Center (MESC) at Portland State University. Reif's research focuses on Algeria, Pakistan, the Middle East, and Muslim world.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

January 2

-

February 6

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.