Note from the CPD Blog Manager: This piece was co-authored by Elad Segev, lecturer in media and communications at Tel Aviv University. Framing theory deals with the manner in which issues, events, and actors are portrayed...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Making the Geopolitical Connections: Turkey and China in Syria

The former British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan once commented that the most difficult thing about politics was "events, dear boy, events." Events can be helpful or unhelpful coincidences for statesmen. No one would suggest that Russia was in any way related to the Paris attacks. Nevertheless it has played out well for Putin as Hollande has sought to involve Russia as a key member of the coalition against Islamic State. The Kiev government's relationship to the attacks that cut off electrical supplies to the Crimea is more ambiguous. However, the Ukrainian government is increasingly concerned that Russia will leverage its role in Syria to secure a beneficial deal on the Ukraine. Stressing the costs of Russia's occupation of the Crimea, and reminding the West of Russia's nefarious role there, certainly suits Kiev's purpose. Likewise, Turkey may not have shot down the Russian fighter for geopolitical purposes, but it will take advantage of the incident to put a spoke in any Western rapprochement with Russia (and Iran) over Syria.

The West needs to engage seriously with Turkey. Turkey looks to be the major loser in any settlement of the Syrian (and Iraqi) crisis. Turkey's major regional rival, Iran, will probably end its international isolation and gain influence. Turkey's Syrian allies will be marginalized. Turkey's declared enemy Assad may survive for a while, and at worst will enjoy a comfortable retirement. Most crucially the Kurds will secure a de facto if not de jure state. Erdogan is increasingly authoritarian and increasingly mistrustful of the West. Turkey, rejected by the EU, marginalized in the Middle East, with a failing economy and internal political instability, risks becoming another destabilizing factor in the Middle East. The West, and especially Europe, must pose the question "what does Turkey get out of the defeat of ISIS," and find a convincing answer.

Ignoring Turkey's interests will be dangerous. Turkey no more wants a direct conflict with Russia than Russia wants one with Turkey. But Turkey does have a convenient proxy war at hand in the frozen conflict over Nagorno Karabakh. Azerbaijan has spent the last few years using its oil money to build up its military with a view to retaking Nagorno-Karabakh from Armenia. But the collapse in oil prices has hit its economy and the window of opportunity for a successful military operation may be closing. A Turkish-encouraged Azeri attack on the enclave would force Moscow to choose between Yerevan and Baku (so far Moscow has guaranteed Armenia's security while hedging its bets by selling weapons to Azerbaijan). For Turkey this could be a low risk option. But if Moscow is seen to support Christian Armenia against Muslim and Turkic Azerbaijan it could have serious implications for Moscow's position elsewhere in Central Asia, and the Middle East. At the very least, it would put serious strains on the Eurasian Economic Community. Nagorno Karabakh could be a conflict too many for Putin and the Russian military.

Like the British Empire before WWI, the U.S. is ambivalent about its superpower role. But this ambivalence generates a loss of confidence among allies and uncertainty among rivals.

The Ukraine is less geopolitically challenging for the West than Turkey. There is little prospect of Russia returning the Crimea. This makes it all the more important to secure a good deal for the rump Ukraine, which guarantees not only its borders and security, but also its economic and financial stability. If Putin wants sanctions lifted, then he must still pay a price, in the form of guaranteed security for Ukraine and the other former Soviet Republics in Russia's Western Near-Abroad. Europe has its own leverage over Russia. It must not give the game away in exchange for Russian support against Islamic State.

China's role in the geopolitical nexus has been underestimated. Only Merkel invoked China to put pressure on Putin over the Ukraine. Otherwise the West, led by the Obama Administration, has seemed determined to drive Russia and China together into an anti-Western embrace. China's direct relevance in Syria may be limited. But it too has declared war on Islamic State after the decapitation of a Chinese hostage and has its own jihadist problems in Xinjiang. If France is insistent on bringing Russia into an anti-Islamic State coalition, it should bring in China as well. Partly as a means of bringing China ever more into the processes of global governance, and partly as another channel for applying pressure to Moscow. China may have a limited military role, but it could play a significant economic role in post-settlement reconstruction. If China wants to proclaim its standing as a world power, it is time it got its hands dirty in the Middle East.

Many of the problems in constructing an anti-Islamic State coalition arise from U.S. disengagement with the world. Like the British Empire before WWI, the U.S. is ambivalent about its superpower role. But this ambivalence generates a loss of confidence among allies and uncertainty among rivals. Tensions increase as regional rivals seek to re-calibrate their security assumptions. In 1914 uncertainty about British intentions was a factor in the outbreak of WWI. In 2015 Obama's indecision has allowed Putin's irruption into Syria and may yet cede leadership of the anti-Islamic State coalition. This would have serious implications for the future of both NATO and the EU. The main lesson to be drawn from Macmillan's preoccupation with "events" is the need to be adaptable, but within the framework laid down by a coherent narrative that prevents the statesman being constantly blown-off course by events. In the U.S., such narrative frameworks are called Grand Strategy, which brings us back to the inability of the West any more to do strategy.

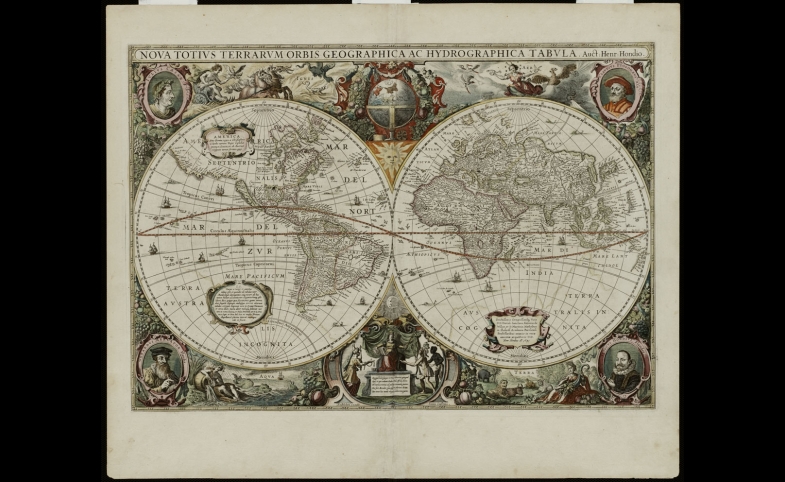

Photo by Norman B. Leventhal Map Center | CC BY 2.0

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

March 9

-

January 28

-

February 6

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.