There is ample evidence that we are living in an increasingly adversarial moment—a world of global terrorism, refugee crises, and divisive partisan and nationalist politics. While mitigating cultural conflict through...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Six Ways States Resist Cultural Diplomacy Hegemony

Cultural diplomacy is often defined as a subset of public diplomacy. New cultural diplomacy is supposed to serve as an instrument for promoting better cultural understanding between the public, and simultaneously it should contribute to the trust-building efforts of the government while achieving goals that are beyond the scope of national interests (for a detailed definition, see this article by Hwajung Kim). Nevertheless, cultural diplomacy is still being utilized to serve national interests, and, in practice, partnering countries can even perceive each other’s cultural diplomacy activities as threats.

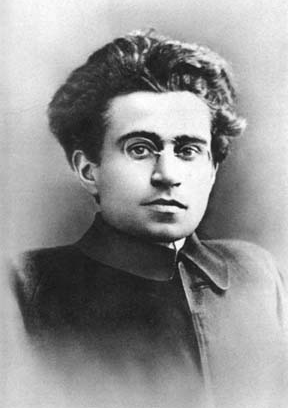

These concerns can be explained with Antonio Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony. Gramsci claimed that the ruling class could dominate the society by manipulating the culture which incorporated beliefs, norms, explanations, perceptions and values. The constructed understanding of the world built by the ruling class becomes accepted as the cultural norm and the way of life for the population. This theory is relevant for a cultural diplomacy context as well.

These concerns can be explained with Antonio Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony. Gramsci claimed that the ruling class could dominate the society by manipulating the culture which incorporated beliefs, norms, explanations, perceptions and values. The constructed understanding of the world built by the ruling class becomes accepted as the cultural norm and the way of life for the population. This theory is relevant for a cultural diplomacy context as well.

Ongoing cultural penetration of country A by country B can create risk for the country A elites and ruling class. The worldviews that elites and the ruling class of country A impose on their population might be challenged, although cultural diplomacy activities are motivated by the will for mutual understanding and common good efforts. Even the most innocent cultural diplomacy activities of one country can contain symbols and messages that would undermine worldviews produced by the elites of the recipient country.

In this context, it is not surprising that countries can implement methods to oppose cultural diplomacy.

In this post, I would like to share thoughts on some historical evidence and practice showing how the ruling class and elites (represented with governments) tried to protect their population from the cultural diplomacy activities of other countries for the sake of maintaining ruling status.

1. Self-isolationism. Some time ago, the simplest way to prevent a country’s own population from being exposed to foreign culture was to reduce opportunities for that foreign culture to sneak into the country. Among historical examples, the self-isolationist policy “sakoku” of Japan during the Tokugawa shogunate could be mentioned. Almost no foreigners could visit Japan at that time, and very few Japanese could leave the country.

2. Digital self-isolationism. It is hard to imagine a totally isolated country nowadays, mainly because of technological development and globalization. But still, at current stages, states can establish restrictions on the use of specific means of information delivery or information sources (let’s remember the Chinese Great Firewall policy towards such sources of information like YouTube or Facebook). The efficiency of these methods is debated because people still can use anonymizing apps and VPNs to access banned foreign websites. Even in the places where the Internet connection is poor or unavailable, people manage to receive an updated cultural product from outside (for example, El Paquete in Cuba, which is downloaded content that is spread through an informal network).

3. Ban a particular foreign culture. Another method that country elites have used to prevent the population’s exposure to unwanted culture is the ban of cultural products from a specific state. For example, after the collapse of Imperial Japan in 1945, South Korea introduced a ban on Japanese cultural content, which was very strict until 1998. And while most of the restrictions were lifted, still there is a portion of Japanese cultural products (like TV shows in the Japanese language) that are banned in South Korea. And again, even though Japanese cultural products were restricted in Korea, they were present and circulated among people illegally.

4. Ban a particular product of foreign culture. While overall relations between countries can be decent, and cultural exchange can be mutually beneficial, some cultural products might be controversial and can be considered as threatening for the population of the receiving country. In this case, the government might choose to “defend” its own people from unwanted cultural influence and apply censorship towards a particular product. One of the most recent examples is when an American-Chinese animation movie was banned from screening in Vietnam and the Philippines when viewers spotted a scene where a map shows China’s nine-dash line, which is considered by the Vietnamese government as violating Vietnam’s waters sovereignty.

5. Undermine culture without banning. While countries can maintain relations and cultural exchange, states considering cultural diplomacy activities harmful or challenging to elites might choose not to ban the cultural products but try to undermine other countries’ cultures (i.e., make it unwanted and less attractive). An example of this might be policies conducted by major Russian media corporations that are trying to build direct associations between modern European culture and homosexuality, which opposes Russian so-called “traditional” family-oriented values and culture.

6. Replace cultural products of another country with homemade ones. Additionally, it should be mentioned that the country might choose to substitute dominating foreign cultural products with home-country cultural products without banning foreign culture but applying restrictive means (like quotas). For example, South Korea’s movie and series production blossomed in the 2000s (as a part of the Korean Wave), and China imported a lot of Korean TV shows and actively and almost unconditionally aired them (up to 2005). However, inspired by commercial and cultural concerns, China introduced a set of rules that drastically cut down the air time of Korean products on TV while giving priority to Chinese shows. Among restrictive measures were reducing foreign show broadcasting time per year for channels (squeezed to 20 hours per year), stipulating that international TV shows should not exceed 25 percent of daily programming time, and establishing that overseas shows should not be broadcasted in the evening prime time.

What will happen next? Well, from the history, we might learn that foreign culture can find its way to the public despite imposed restrictions: the cultural products will reach the public either through legal means (e.g., broadcasted movies, exhibitions, restaurant chains), or through illegal means. The countries that consider cultural diplomacy as a tool of foreign policy will keep on producing cultural diplomacy products, targeting foreign publics, and finding methods to distribute these products both legally and illegally to the targeted public.

The states whose ruling class considers cultural diplomacy activities as threats will be looking for means to prevent the spread of unwanted messages. These methods will include mastering filtration of the information in the local media (including the introduction of the so-called “sovereign” Internet), replacing information platforms with homemade ones (search engines, messengers, Wikipedia-like websites), imposing advanced censorship regulations, urging the public to dislike and distrust foreign cultures (e.g., advancing creation of fake news) or decreasing interest in foreign cultures.

This battle for cultural hegemony will not end. The foreign state using cultural diplomacy will never stop producing for either political or commercial reasons. To win the battle for cultural hegemony at home, the ruling class will have to unteach the public, make them illiterate, and make them unable to read and understand symbols.

Note from the CPD Blog Manager: Read more on cultural diplomacy in Varpahovskis’ previous CPD Blog post, “Intangible Cultural Heritage as a Driver for Cultural Diplomacy.”

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

January 2

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.